I lost over thirty years in my art journey because I (stupidly) took a wrong turn based on what should have been great advice. Let me tell you about that, how exactly I went off the rails, and what a ridiculously talented Korean artist said that got me back on the journey.

If you care about the process of visual creation, whether it’s you doing the creating or just a spectator’s interest in how all that works, then this one’s for you.

Why does this matter?

Crap, man, I’d like to be thirty years better in drawing and painting! I hate that I stepped away for that long. I’m the chief illustrator for Grailrunner, and its lead writer, and its game designer. I need to get a lot done myself to control costs, but somehow keep a high standard on quality of art to convey the unique (we think) property we’re trying to build with the Salt Mystic line.

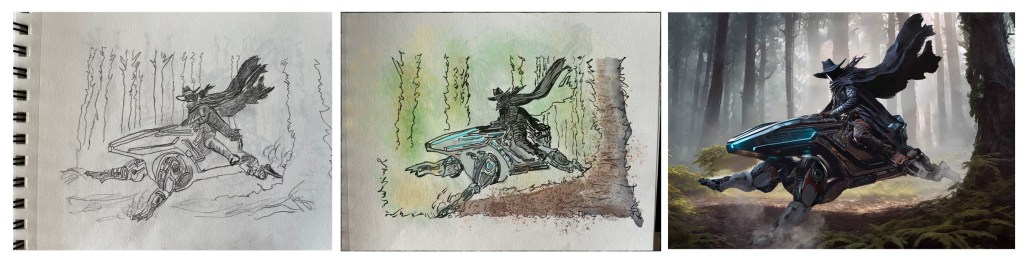

The images below represent the style of work I’m building these days, relying heavily on photobashing and concept art techniques (with folks like Imad Awan as my virtual gurus). The Grailrunner house design standard is semi-realistic digital painting with grungy overlay, western themed adventurers almost always carrying the signature weapon (a gauntlet-based plasma weapon that doubles as a shield in duels), exploring statue-riddled, software-haunted ruins with shimmering dimensional portals. We aim for vibrant or earthy colors, lots of smoke and grit, with implied stories (often illustrating flash fiction on Salt Mystic lore cards).

See the lot of them (and trace my hopefully improving style) at the Artstation account. Yes, I use AI-generated bits to composite exactly like I do with stock images but generally composite everything into something new and paint over them such that the transformation is meaningful and my own.

It gets the job done, at least I think. Still, I wish they were grittier. I wish they broke more new ground than they do. I envy the striking shapes and designs of a lot of concept art out there for cinema and gaming – the kind of images that stick with you even if you don’t know the context. Artstation is great for inspiration, but it can also crush your dreams if you compare yourself to anybody.

Mitchell Stuart, for example. Or Ricardo Lima. Or Raphael LaCoste. Or Greg Rutkowski. Or Ash Thorp. People like this are just on another level.

What’s prompted this reminiscence about bad art advice?

Well, I came across this book called Sketching From The Imagination: Sci Fi by 3DTotal Publishing. I wrote about it here. That was October, which seems like an eternity ago. I posed for myself the challenge of returning to traditional pencil and ink drawing in a sketchbook to push my imagination harder than ever before. The dream is to explore a blank page with loose shapes and vague ideas to summon phantoms into form and create groundbreaking designs and concepts. Then these wild new beasties and tech and colorful characters would then find homes in the fiction or game settings.

How’s that going?

Meh. I was so much rustier than I thought I was. I’ll share some pages here to embarrass myself and stay accountable to you for improving. We’ll get to that. But let’s talk about that advice.

When I was a kid, I filled scores of sketchbooks and countless backs of trashed dot-matrix printer paper my dad had brought home from work. Drawings of super heroes and sci fi vehicles and cities were my jam. Comic books were my main source of imagery, so everything I was drawing had bold outlines and underwhelming composition. The stories weren’t being told by the images in a self-explanatory way – I didn’t think about that sort of thing. I was alone a lot, so I didn’t share these with anybody, nor did I get any feedback.

Flash forward to one day in art class, Middle School I guess, the teacher strolled by to see whatever I was working on and stopped to say something about my approach that resonated with me. He pointed at the paper and said something profound:

“Real world things don’t have outlines. Draw what you see.”

It shook me. Hadn’t thought about that. Good point. So I gave it everything I had to incorporate his advice into how I drew. Back home, hovering the pencil over the paper, for the life of me I couldn’t figure out where or how to make a mark to start the drawing if you couldn’t outline it.

For this post, I looked through some old crates to find a particular drawing that would be humiliating to show but really staked the ground for when I began to turn away from drawing entirely. The picture in my head was a Dungeons & Dragons-style adventure party with a lady wizard, a swordsman, and an elf planning their next move on a morning beach with foamy, ripply water lapping at their feet. Maybe a dying campfire in the foreground with smoke rising in front of them. I couldn’t find it, unfortunately.

Anyway, it was horrid. Everything on the page was so light, you couldn’t even make it out. I was petrified to start drawing outlines again, and I couldn’t see how to force shadows and contrast to draw out the shapes. It threw my perspective. It threw my focus on their faces. It ruined everything. It was the last sketchbook I really did anything with until decades later, at least in any serious way.

Sounds bad. What’s different now then?

I get it now. Youtube changes everything, doesn’t it? Contrasting light and dark, the subtle use of textures, faking details, focusing and directing the viewer’s eyes across the image, and strategic use of busy and rest areas…I never went to art school. That all may be common sense to you, but it’s a glorious rainmaker for me to see all that in action artist after artist, listening to these marvelous and generous people draw magnificent things and explain their thought process as they go. Great time to be alive, isn’t it?

I travel a lot, so I keep an art pack and sketchbook. Pigma FB, MB, and BB brush pens, Staedtler pigment liners, a mechanical pencil, and some Graphix watercolor felt pens. Since October, I’ve put the practice time in almost every night at least for a half hour. It wasn’t a pleasant return.

The dream is to draw from imagination though: new things. What I’ve learned from artist after artist in their podcasts, Youtube or ImagineFX interviews is that drawing from reference is far more common. A lot of the guys you see on video drawing or painting have their reference images off screen.

Reference images! That wasn’t why I got into this gig. If I wanted a copy of an image, I’d take a picture. It was disheartening to me to hear professionals talk about light table tracing for their outlines…to see fantasy illustrators mash up references to form fantasy beasts – all of it copying what they saw. That was my problem back in the first place, right?

Then I came across this genius: Kim Jung Gi. Rest in peace.

Please google him if this flame of wonder is unfamilar to you. He drew from his imagination like a magical fountain spews sparkly fairies. He just walked up to paper and went nuts, drawing fish-eyed perspective, highly intricate intertwined figures, scores of objects and novel, distinct, and interesting characters at a high rate of speed and without slowing. How’d he do that?

That guy didn’t have any reference images. That’s what I wanted. I had to go deep to understand what he did right that I was doing wrong that could unlock this magic. Exploration on the blank page…finding ideas haphazardly that were uniquely my own…I wanted to bottle this magic for myself. How in the world did he get to the point he could do it so wonderfully. Then I heard him say it (through a translator):

“Don’t draw what you see. Draw what you HAVE seen.”

His point was you have to do the reference images and understand forms and shapes in three dimensional space before you can do what he did. He explained the lifetime of sitting in public places filling thousands of pages drawing what he saw and forcing himself to draw it from another angle. That was the key – he drew what he saw with a lifetime of practice, but still practiced summoning those images from his memory to try them from different angles.

He drew what he HAD seen. It was a big realization for me, this idea of examining the reference image – not just to get better at copying it, but to run your mind’s eye all over it in three dimensions to understand it better and to file that away to fuel your imagination.

Now THAT’s what artists actually do. They don’t copy. They understand.

I wish that guy was still alive. He was amazing.

Agreed. Now how about sharing your progress?

Ugh. Here you go. Don’t be judgey. Wish me luck that things improve. Go ahead. Click the book.

Ouch. I hope you don’t lose all trust in me, should you have had any. Photobashing is an entirely different beast than battling blank pages with a mechanical pencil. I’ll keep at it. The beast-shaped robotic vehicle in the header image was a minor victory in this experiment: called a “sporecutter”, it’s the first concept that’s come from the new approach that might actually make it to the fiction. Page 15 in the sketchbook file here is the front runner for the design of an important vehicle in the Mazewater: Master of Airships novel I’m working on. That’s another possible win.

That’s what I wanted to talk to you about today. I hope it was enlightening or helpful, should this be a journey you find compelling for yourself. Otherwise, I hope I still brightened your day a bit and made you think.

Till next time,