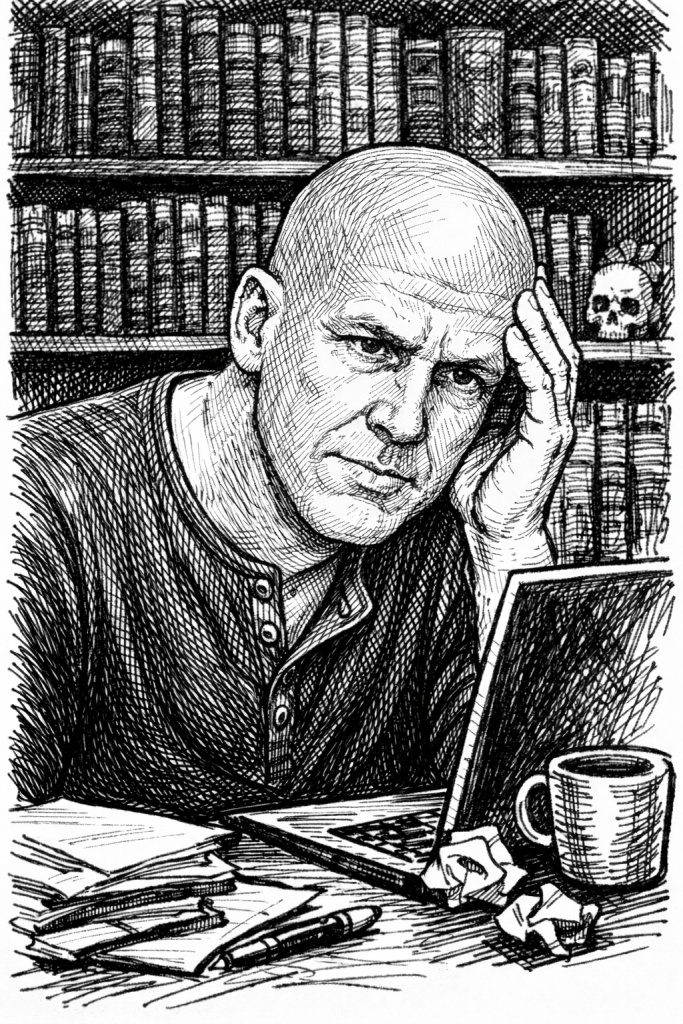

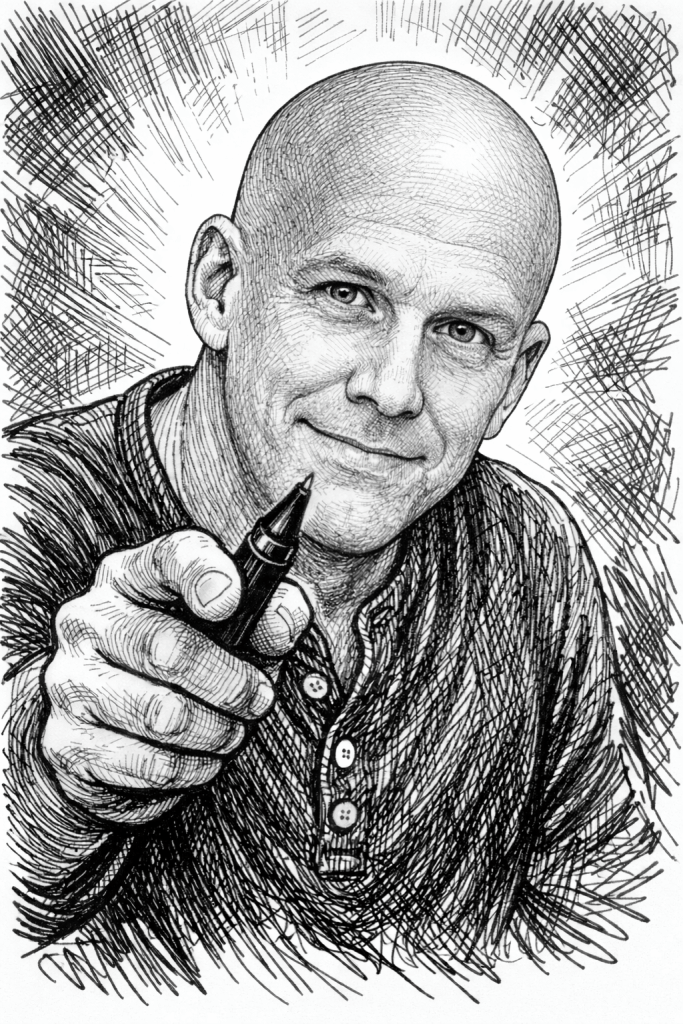

It started in October 2023. I used to fill sketchbooks with superheroes and sci-fi vehicles when I was a kid, but I hadn’t really touched it seriously in decades. Then I came across one of the marvelous Sketching From The Imagination books from 3DTotal, and it blew my mind! The idea of drafting my own concept art to summon up interesting ideas for the novels and games of Salt Mystic intrigued me.

But I sucked. And I’m hoping to keep that in the past tense, but we’re not there yet.

I wrote here before about some art advice I’ve picked up along the way, one of which crippled my drawing for a very long time. That post contains a couple of sketchbook updates to keep me honest and working to improve. It’s not super fun to share a journey because I would prefer anybody stopping by Grailrunner to check us out think that I’m a powerhouse of creativity and master craftsman of the imagination.

Still, maybe I’ll get better if I’m periodically embarrassing myself!

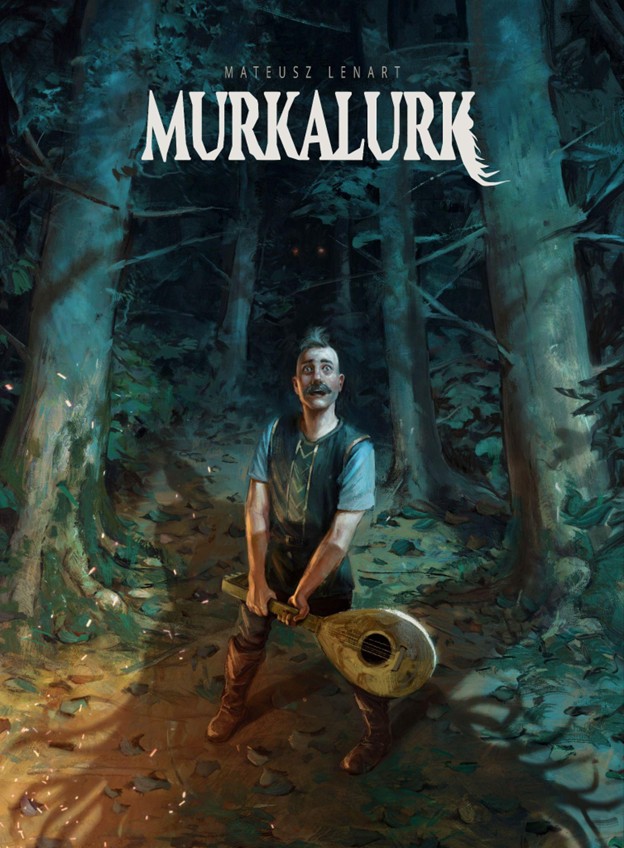

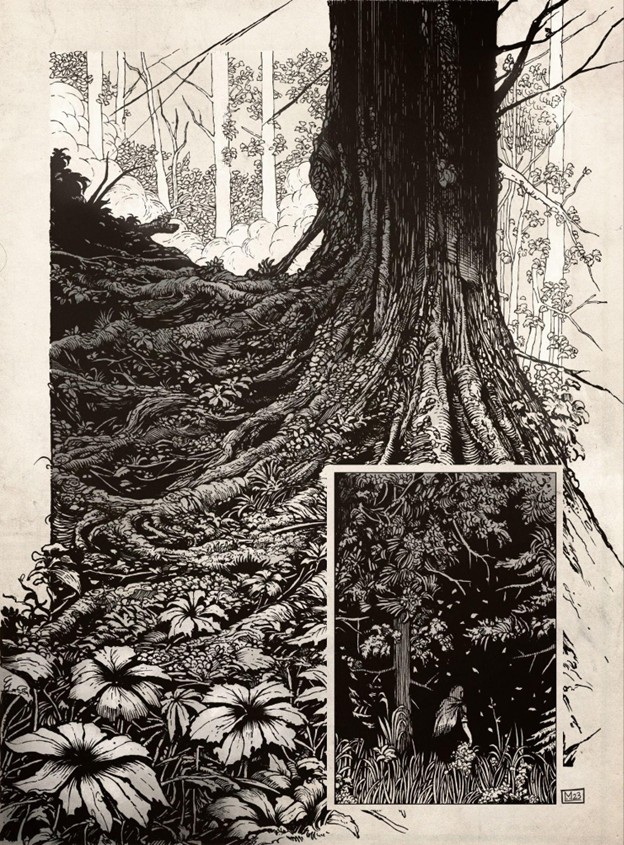

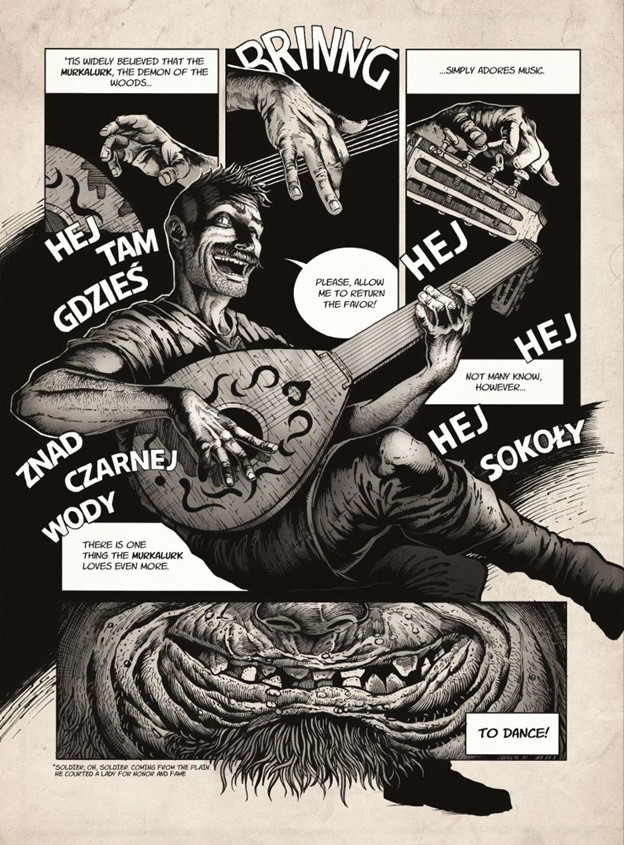

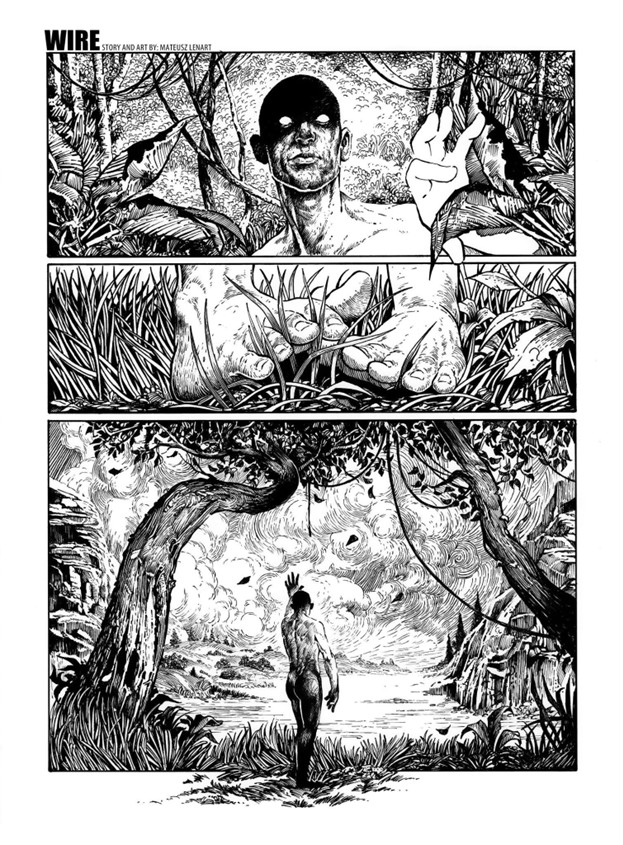

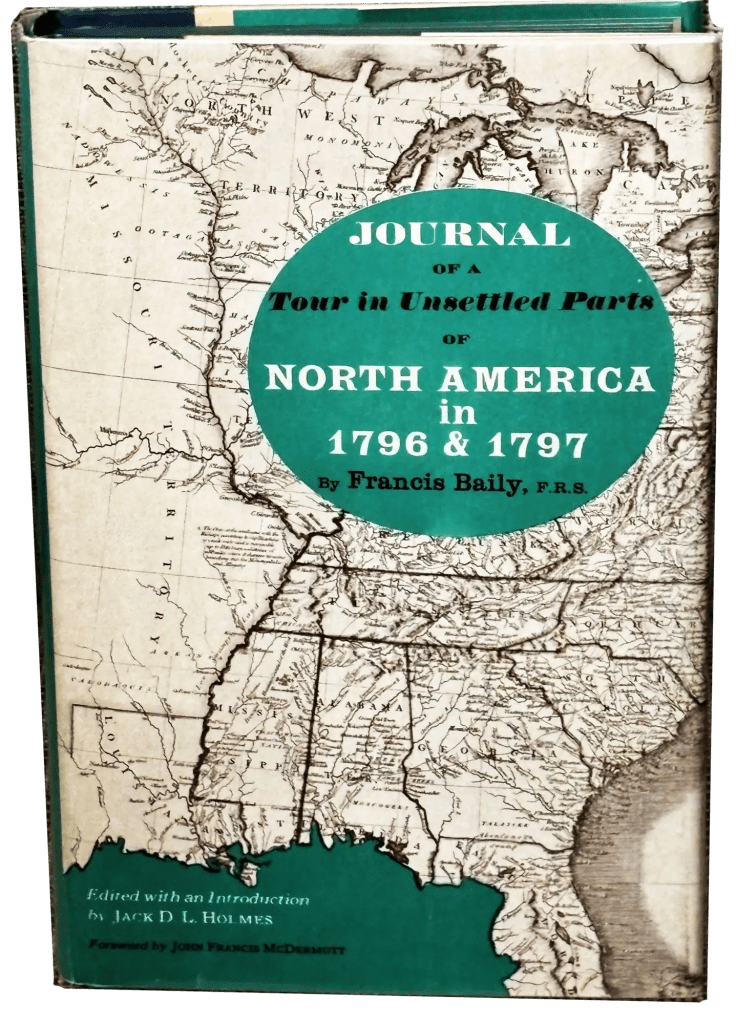

Then I took a road trip with my wife this past summer to the Mississippi Blues Trail and came across a hardbound compilation of 1890’s era Harper’s Magazines. I wrote that up in I Found a Pen & Ink Masterclass in an Old Antique Mall. Suddenly, traditional pen & ink became an obsession as I saw what Charles Dana Gibson and Franklin Booth and guys like that could do! My Booth research culminated in Franklin Booth: Engraver of Light and a trip out to see the Indiana house where he grew up and kept a studio. I also got the chance to interview a modern-day ink wonder-worker with Mateusz Lenart.

So what’s your process to learn and practice?

Two sketchbooks now. One is for drawing from imagination or freehand with cobbled-together references. That’s to work on my ability to reproduce things I’m looking at with tweaks and from different angles, and to experiment and be messier. For the other sketchbook, I generate a clean reference digitally with stock images, AI elements, or a combination of these, then trace the outline with a light table and work from the reference for rendering.

Any particular destination in mind here?

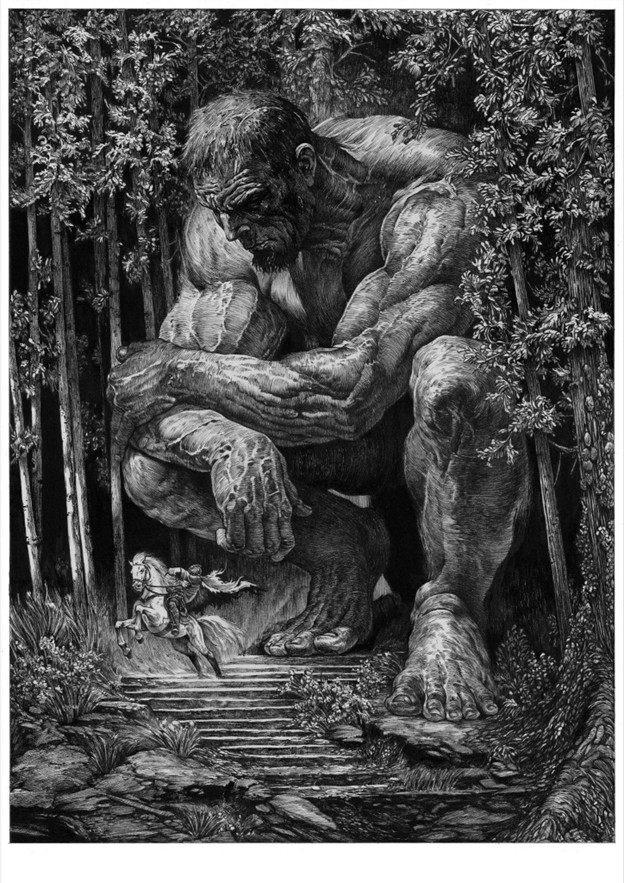

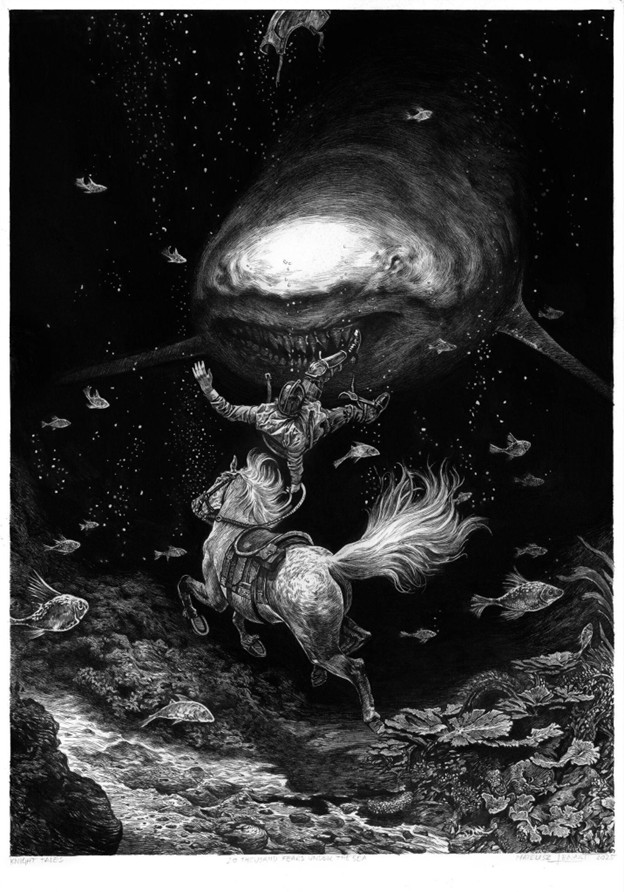

I’d like to combine the visual storytelling of Norman Rockwell, the ink style of Bernie Wrightson, and the sci-fi visual innovation of Juan Gimenez. That isn’t too much to ask, is it? Specific artists I’m looking at for their ink work are Charles Dana Gibson, Franklin Booth, Sergio Toppi, Bernie Wrightson, and Joseph Clement Coll.

Wrightson. I mean…do yourself a favor and take a look at these!

So what have you learned?

Let’s do the countdown, shall we? Fifteen things I’ve learned in practicing traditional pen & ink and analyzing the masters:

#15 Using references is not cheating

I’ve got a love/hate relationship with using references because copying things wasn’t why I originally got onto this train, you know? Still, images in my head fade too quickly for me to look inward and draw what I see there. You do what you’ve gotta do, right? It’s been enlightening for me to see just how many professional artists use photographs and composite stock images for their references.

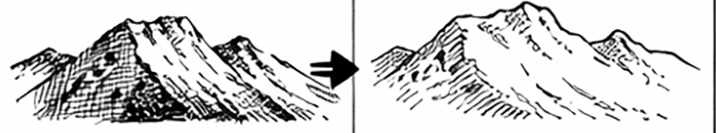

#14 Professionals work in layers

The masters lay down their structure, they build deep shadows, they add texture, and their pictures often look terrible in progress as it seems they’re destroying their own work. Then it somehow, magically, takes shape in the final product. The picture doesn’t have to spontaneously drop onto the page fully formed. It builds in layers. To be honest, I’m still struggling with this one, but I know there’s truth here.

#13 Strategic overlaps simulate depth

I couldn’t figure out why my grass, weeds, and trees in practice landscapes looked so awful and flat. It was driving me crazy. Then I took a photo of some plants growing by a lake near my house and made a strong effort to make the thick blades translucent and allow some shadow of a leaf behind it to be implied. That was a watercolor painting, but it got me thinking. Then a Stephen Travers tutorial on Youtube spelled it out for me that I was rushing my plants and tree limbs with flicks of the pen when a few strategically placed blades or limbs up front with detail, contrasted with flicks behind them and shadows below them would imply exactly enough to look FAR better.

#12 Texture matters more than hatching

I know this is true, but I can’t make my hands do it. Driving me nuts, honestly! But I’m abusing hatching and slapping lines everywhere to add shadows and it’s looking like washed-out, hairy messes at times. I see a guy like Alphonso Dunn teaching texture and realize what I’m doing wrong. You’ll see a couple of leaf studies in the accountability sketchbook below where I bottomed out on this. It’s something I’m keeping in mind as I work to improve, not something I’ve mastered.

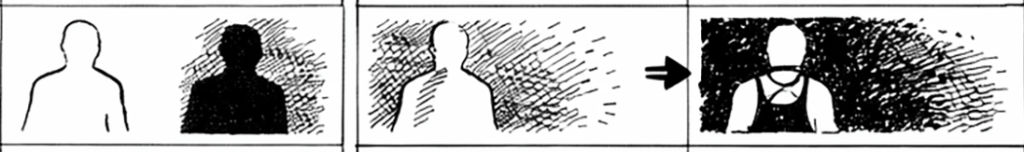

#11 Simplify the reference and find the story

Photos capture everything. Reproducing them is compelling. It feels like practice. Then when I’m done, somehow the photo looks fine with all that detail and my drawing looks like a bowl of spaghetti fell on the paper. I’ve come to realize that “focal points” and “guiding lines” in a drawing really work, and that the viewers’ eyes really can be steered. Practically every professional artist seems to be saying the same thing on this – start with what story you want to tell, then draw only that. Just hint at everything else, and try not to even do that.

#10 Contrast is what pulls forward on the page, not line weight

I had been getting the impression from on-line inker tutorials and an Arthur Guptill book that dark shadows and heavy line weights look like they’re closer and lighter lines look farther away. In the sketchbook at the bottom of this post, you’ll see a drawing of a girl and a horse with a spilled water bucket where this came home for me. I needed the girl and horse to look closer, but there were dark shadows behind them in the stall, which crippled me. I mean, if I darken the shadows, the figures will be lighter and will look farther away when that’s the opposite of what I wanted! I realized with that one that contrast is what draws the eye, not darkness, so uniform shadow behind them is A-OK.

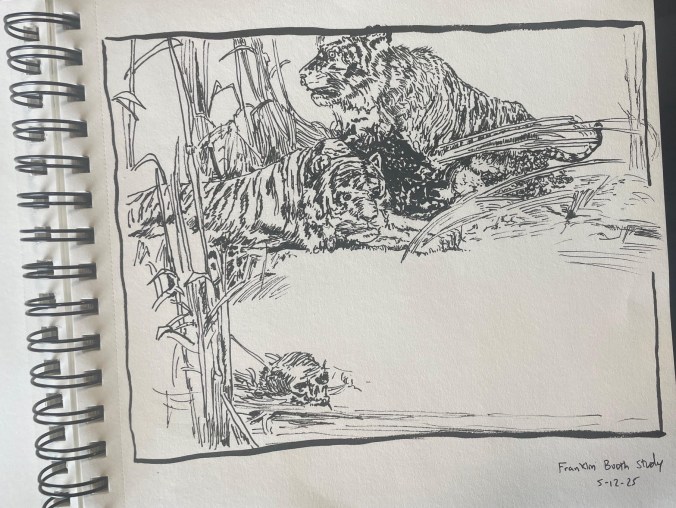

#9 Leave rest areas

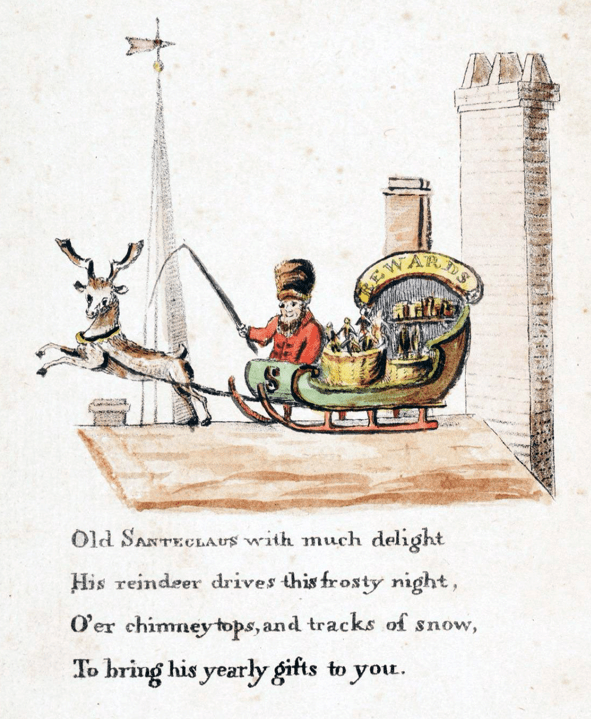

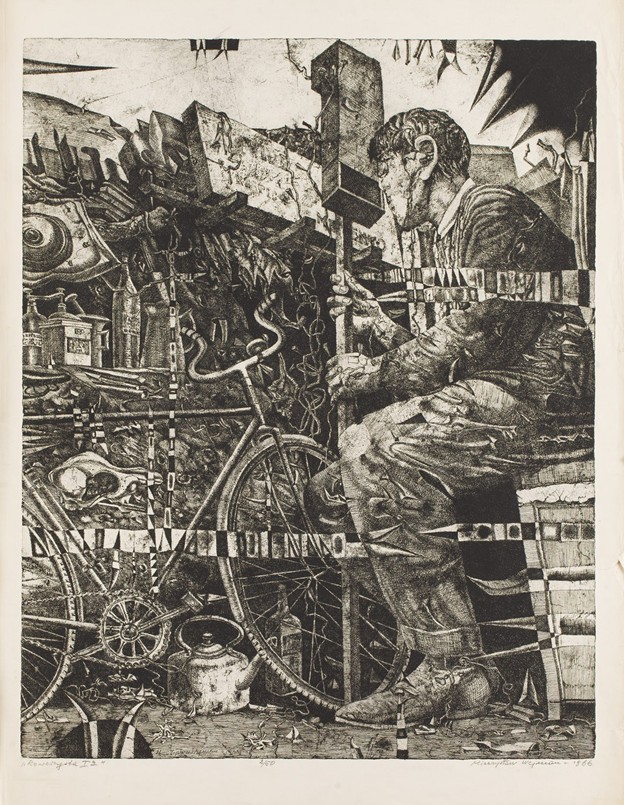

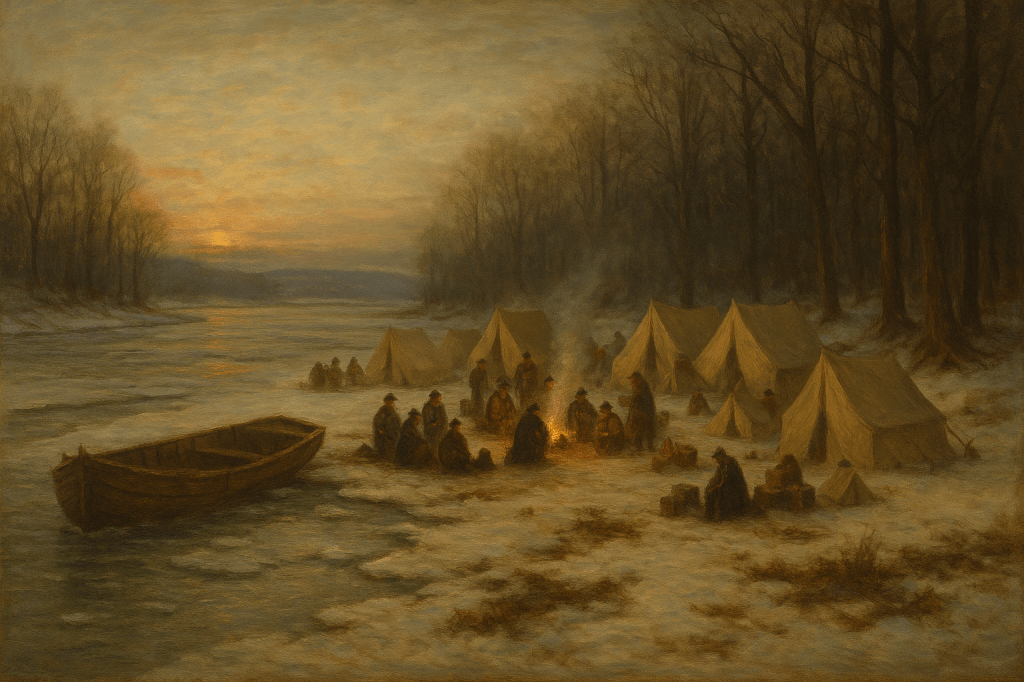

This is a study I did of a Franklin Booth masterpiece. I usually feel a strange compulsion to fill the entire image with stuff. Can’t help it. Seems like the job. Then you see a composition like this where he leaves that wide open space for water, and you really get the importance of leaving something without details to keep things from getting busy.

#8 Shadows should be bold, should connect, and should be interesting

I first learned this from a watercolor artist named Matthew White. He kept going on about “connecting your shadows”, and “make them interesting”, and for a long while, I had no idea what he getting at. In my head, if the reference has deep shadows, then add them. If it doesn’t, then don’t. Then you realize at some point that you’re not trying to copy the reference and there are emotions at play here with values, shapes, and configurations. Just like a bass guitar anchors music and things sound thin and weaker without it, the deep shadows are an anchor for the image.

#7 Outlines are okay, but be smart about them

“Things in the real world don’t have outlines.” That was the art advice that threw me for decades. I couldn’t see how to draw something without putting a pencil or pen to paper at the edges. With pencil, it was easier to smudge and add gray areas, so not quite as bad. But when you switch to pen & ink, every time the tip touches the paper, it’s crisp black. Walter Crane in Line & Form stated something in words that I was noticing with the ink masters – you can avoid outlines entirely by effective use of contrast.

However, outlines can also be fine with a smaller tip (like 0.005 liners) or if you break them up in the highlighted areas where the light is hitting.

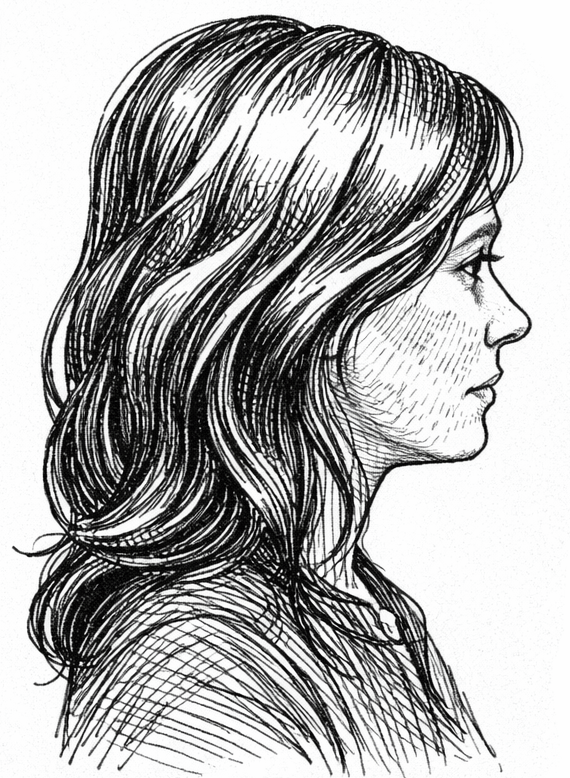

#6 Think in clumps and masses for hair

Trying to draw hundreds of lines to simulate hair is crazy. It turns out that hair, much like foliage and grass, can be clustered into value patterns – basically grouped highlights and grouped shadow shapes. In the highlighted area of hair, a few well-placed strokes hints enough for the viewer’s brain to fill in the rest.

#5 Work in larger formats if you can

I think in 5 x 8 and 7 x 10 formats because sketchbooks often come like that, and it’s where I’m always putting my drawings. I have found, however, that many of the impossibly detailed drawings that catch my eye weren’t made in a pocket sketchbook. They were on much larger Bristol board or something like it. They were built large with room to breathe, and became sharp and complex when shrunk down in reproduction on the page or on a website. This comes to mind when I’m squinting at a drawing and switching to my finest liner to try and make something visually impressive at a small scale.

#4 Line hierarchy

As a kid or in school, I drew with just the one ballpoint pen and never considered needing different thicknesses. It wouldn’t have dawned on me to do so. Those early 20th century ink masters were using dip fountain pens which flexed to allow for varying thickness – but good luck keeping yourself in reasonably priced fountain pens and ink these days. Ahhh- but brush pens! Like the Pentel Sign Brush Pen that has that cool, stiff and tiny brush you can push on. And liner sets like Pigma and Uni, with multiple options to choose from. I have found that varying line thickness is visually appealing, and strategic use of bold lines for emphasis and lighter lines for highlights can help lead the viewer’s eyes.

#3 A good drawing can save bad rendering, but a bad drawing is hopeless

A weak composition or poor drawing absolutely cannot be saved by even superb hatching and shadows. It just looks like mud, and mistakes on faces or eyes or with the perspective are obvious no matter how awesome your rendering. I’ve seen that pencil drawings restrain me too much and make the drawings too clean, which I need to fix. But I’ve also seen how wobbly and searching my lines are when I don’t do a pencil drawing. I’m wondering if a very light, minimal pencil drawing that I use like a jazz score might be the compromise I need.

#2 Restraint looks better than over-working – the viewer needs less than you think

I over-work my drawings. Definitely. It happened even today, with me thinking this very thought. Every pass of hatching on the most recent drawing in the sketchbook, I thought to myself – easy…that’s probably enough. Then I kept hatching. I don’t know why. It’s crazy. Anyway, professional artists render much less than feels like they should. They hint where I draw. I’m especially bad with eyeballs; some of the professional works I’ve analyzed barely stroke the pen to suggest eyes where I’m drawing little ovals and working like crazy to make it look good. Nah…restraint is better than spelling everything out. Stop early.

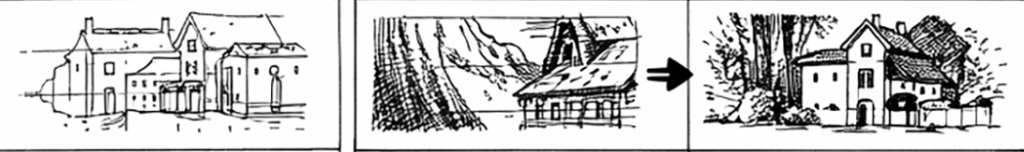

#1 You can still fade distant objects with pen & ink

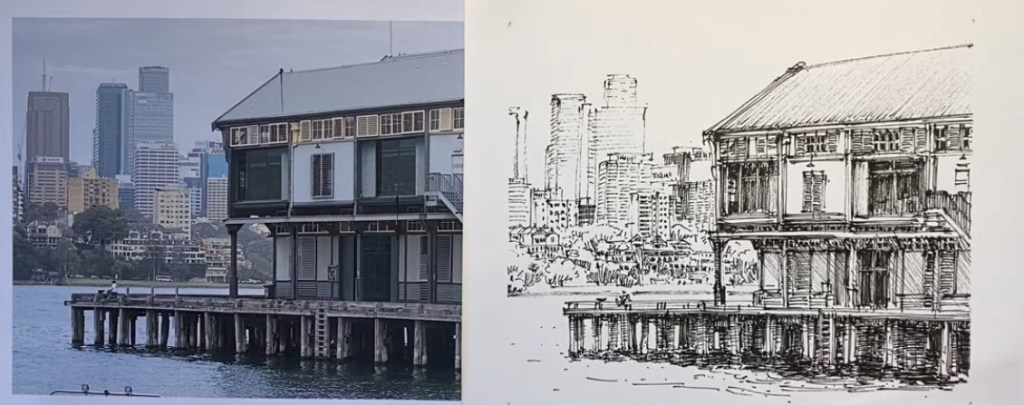

This one’s funny. I’ve tried a few landscapes where, like a dummy ignoring the lessons even in this post, I’ve meticulously tried to simulate everything in the distance and modified the hatching to experiment with every kind of value you can imagine. Then, I was watching Stephen Travers (below) draw a building on the shore with a city in the distance. I thought to myself as he got started – oh, man, is that detail going to look like a big, messy pizza when you’re done! But he used much thinner lines and wider spacing with fewer marks in the distance to avoid rendering everything equally and it looked amazing. The focus was right where he wanted it – on the building up close.

Okay, that’s a pretty good list. Let’s see that sketchbook then!

Let’s do it. Be kind.

*

And that’s what I wanted to bring you today. I hope it’s okay to share these lessons learned as I go, even though I’ve got so much room to improve.

Till next time,