I get it, man. You can’t get excited about Athanasius Kircher and talk to anybody about him because of the reaction.

“Who?”

Right. Well, he was awesome. If I described him as a Jesuit scholar who lived in the 1600’s, your eyes might roll back into your head before I really got started. But if you imagined him as he was, it might change your life. Here was an insanely curious and wild mind, delighting in machines and ideas and excitedly walking people through his museum of curiosities (talking statues, moving figurines, a room that rained, that sort of thing) delighting people and scaring the bejeesus out of them. He particularly reveled in shocking his visitors with devices and marvels till they accused him of consorting with demons, then opening the compartments and hidden panels to patiently explain the mechanics of it all.

“See, no witchcraft. Just machines. Cool, right?”

Let me back up, explain what I’m on about with this guy, then land on turning on one of his marvels for ourselves. My point here, as always with this site and anything we do at Grailrunner, is inspiration. And this guy had it in bucketloads.

Years ago, I became enamored of the old time philosophers like John Wilkins and Gottfried Leibniz inventing entirely artificial languages to construct perfect ones, with crystalline precision and not linked to particular cultures. (I included one called ‘Mast’ for Recorders in Tearing Down The Statues in remembrance of that particular bunny trail). Somehow in all that, I came across Athanasius Kircher’s work, Polygraphia Nova. This little gem was intended to solve the problem many emperors had of the various languages their subjects spoke, though that isn’t exactly my point today. I remember thinking this Jesuit monk or whatever just seemed outlandishly intelligent and curious about everything, but I dropped his trail for years.

Ahh, but recently, I came across this nugget here (which you need to order now and read for yourself).

If you are at all attracted to the old-time book illustrations where maps and Egyptian symbology and impossible contraptions come alive in fascinating engravings, this one’s for you. That was one of Kircher’s master strokes – as Jesuit priests from all around the world sent him writings and curiosities, like he was a Grand Central Station hub for the information of the day, he captured so much of that with a team of incredibly talented illustrators and a willing publisher. And man, oh man, did he experiment and play with those ideas to draw them to their extremes.

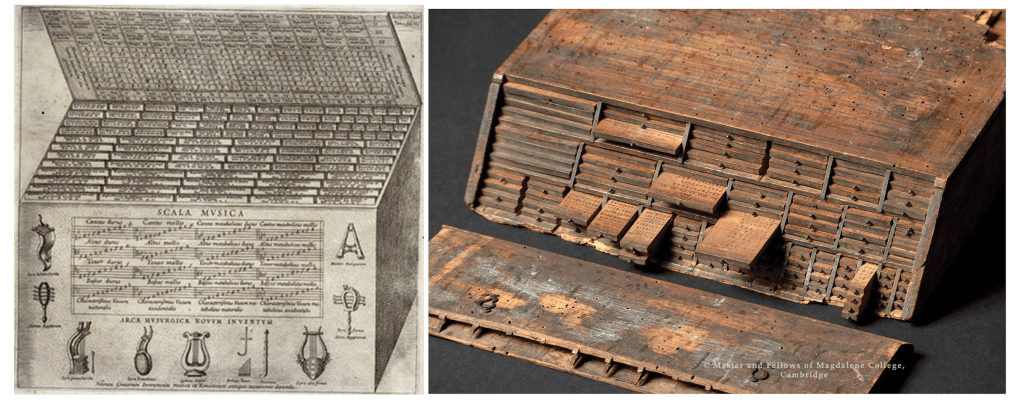

One invention that particularly caught my attention here was the Arca Musarithmica, which was billed as a mechanical composing tool to be used by anyone without musical talent but who needed a piece of music suited for textual phrases in any language. Say, for example, a priest in South America speaking some Quiche Mayan who needed a hymn but couldn’t write music. Here was a mechanical means of doing so.

Now how in the world, I thought to myself, would a machine do that?! Don’t bother with Google here, because I lost hours chasing terrible explanations written by people who can’t water down their music theory enough for laymen to make any sense. Seriously, it was frustrating reading one article after another showing the same images but explaining things differently, and nowhere was anyone reproducing the actual device symbology clearly enough for me to puzzle it out for myself.

Then I found this genius piece, written by Phil Legard.

I saved it as a pdf in fear that the Internet gods would one day allow this masterpiece article to vanish from history. Clear, lucid, well-illustrated, with examples and comprehensive reproductions of the components. Dude should get some credit for this particular public service, so follow the link versus the download if you can. It’s a bit old now, but worth your time.

Here’s what the ‘device’ looked like:

In reality, it’s a box with a bunch of wooden slats inside that you pull out based on the syllable count of your text and the mood of the music you’re looking for. Phil walks the reader through a clear example, but I’ll do it here too to give you a flavor of the process:

- Choose your meter based on the syllable count and rhythm you want (remember meter from school – like iambic pentameter and whatnot?) Let’s use the Grailrunner tagline: “Dreams are engines. Be fuel.” That’s six syllables, so it easily corresponds to Euripedean meter with its six syllables per line across four lines. You’ve got three other choices of meter here, which the box explains.

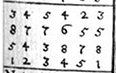

- Pull those Euripedean slats out of the box though:

3. First line’s the one on the left, so it’s showing several choices of melodies for me to pick from. Each block of four rows of numbers corresponding to note sequences (which I’ll explain that conversion shortly) from four different voices (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass). That’s why there are four per block. You pick one. I’ll go with the bottom one:

Here are four note sequences for four different instruments.

4. Just knowing the notes isn’t enough – you have to know how long to hold them. Loads of options at the bottom of that same first slat. Phil and I choose this one: 1/4, 1/8, 1/4, 1/4, 1/2, 1/2 because Kircher’s pupil chose it when he gave his example back in the 1600’s. Whatever. I don’t know enough about music to say if it’s a good choice, and that’s Kircher’s point anyway.

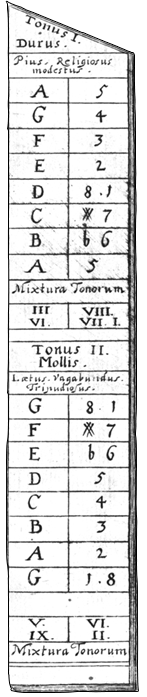

5. Notice at the top of that slat it shows which ‘tonus’ you can pick from. That’s the mood of the piece you’re composing, about which any knucklehead should be able to form an opinion. We can pick from 1, 2, 3, or 4 from the table below:

Mood selections Kircher provided, called ‘toni’

Phil and I chose the second one, ‘happy, strolling, dancing’, though ‘warlike, rousing, glorious’ would be pretty awesome as well. So we pick out the corresponding slat for that tonus (bottom of the slat where it says ‘Tonus II’). That’s our map to convert those numbers to actual musical notes.

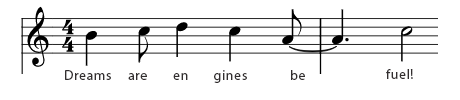

I’m totally stealing Phil’s example because I don’t have the patience to figure out medieval musical notation on flats and naturals:

There are options to get more complicated with counterpoint and different rhythms for the voices, but let’s stay simple. We actually have all we need:

Wow. I’ve found an app called ‘Playscore 2’ that can read musical notation and play it in Midi voices. I may give that a shot so you can hear my new masterpiece here.

Anyway, that’s enough of that. My point was to introduce you to Kircher, let you get to know how his mind worked, and get you inspired. His expansion of these combinatorial methods into a more ambitious device, one to plan cities and do mathematics and whatnot got me thinking about using Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey and the Salt Mystic Sourcebook to generate some interesting backbones for some thrilling tales of wonder. I might give that a go later and come back to you with it.

So that’s it for the day, guys. Hope it was interesting. Let me know what you think. Have a great week!