I’ve written here on Grailrunner before about how interesting 19th century French fiction can be – in that case, the haunting tales of Guy de Maupassant who went entirely insane but wrote great stories about it. And I’ve mentioned here before how fascinating a concept it is to me, the imaginative construction of a fabricated world in all its intricate detail – in that case, the review of Pfitz, by Andrew Crumey. I suppose if all I wanted to discuss today was a complete fictional world I would just direct you to Harn, which if you don’t know what that is, you should probably go check that out.

But I thought instead I’d try and make something more accessible for you than maybe it would be otherwise. Something incredible in its design and execution, audacious in its ambitions, and a work of literature that stands among the finest we have.

The Human Comedy by Honore de Balzac.

“I thought you talked about science fiction and fantasy here – what is this?”

Easy there. There are some incredible points to admire here, so it’s worth taking in a few paragraphs to see what all the fuss is about. As always with Grailrunner, our aim is to study and fuel the imaginative process, so anything we can learn or use as inspiration is fair game.

“OK, so what’s it about?”

It’s a series of 91 inter-connected works (novels, novellas, and short stories) intended to depict the entire spectrum of French society after the fall of Napoleon, with the scope and ambition of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

If you’ll allow me a little Google-Fu:

Here’s how Balzac explained his vision for The Human Comedy:

- A “history of manners”: Balzac intended to be a “secretary” transcribing the “history” of society, focusing on “moeurs” (customs, manners, and morals) – something he believed hadn’t been fully attempted by previous historians. He sought to go beyond surface events and reveal the underlying causes of social phenomena.

- A comparison to Dante’s Divine Comedy: While his title alludes to Dante’s work, Balzac focused on the worldly, human concerns of a realist novelist rather than a theological framework.

- Observing and depicting “social species”: Balzac’s inspiration came from comparing humanity to the animal kingdom, recognizing that society modifies individuals based on their environment, creating distinct “social species” similar to those in zoology. He aimed to depict these social species in their entirety, not just as abstract types, but as “real, living men”.

- The power of storytelling: Balzac, a master storyteller, was fascinated by the power of stories and the dynamics of human interaction around shared narratives.

- Social structures and human nature: Balzac’s work is grounded in sociology, exploring the complexities of human beings and the deep-seated immorality within social mechanisms that often favor the corrupt over the vulnerable. He believed society, while having the capacity to improve individuals, also exacerbates their negative tendencies.

- The transformative power of societal change: Balzac documented the significant changes happening in France during his time, including the rise of the bourgeois class and the clash between traditional and modern values.

- Psychological depth and individual experience: Balzac emphasized the importance of psychological insights and the influence of social context and personal experiences on character development. He aimed to create characters with a wide range of human qualities, both positive and negative.

- Realism and naturalism: Balzac was a pioneer of literary realism, using extensive detail and observation to portray society accurately. His meticulous descriptions of settings and objects bring the characters’ lives to life, and some critics even consider his work to have influenced the development of naturalism.

In essence, Balzac sought to create a comprehensive and insightful portrayal of 19th-century French society and the human condition within that context. His focus on the interplay between individuals and their social environment, the complexities of human motivation, and the power of societal forces has had a profound and lasting impact on literature.

“Wow, man. That sounds boring. Why are you so jazzed about it?”

I get that – I really do. What first caught my attention many years ago about Balzac was a comment I read that hit me like a ton of bricks. I don’t even remember what article or book I was reading, but when I came across this statement, it felt very much like one of those transformative ideas that has enough gasoline to in some small way alter the trajectory of your life. And though I struggled mightily in the past to unlock just what that writer was talking about with The Human Comedy, I’ve thought about this quote many times since that day I first read it.

“Balzac ranks along with Dickens and Shakespeare as a creator of souls.”

A “creator of souls”. Wow. As a writer, I really…really…needed to understand what that looks like and how to engineer it in my own writing. What exactly was the magic that people like Shakespeare, Dickens and this Balzac person were sprinkling into the pages that brought their characters to eternal life in our minds? What made their creations arise from the page like that to merit their author being granted a title like that?

“What did you find out?”

I tried to dip in somewhere among the 91 works over the years and found out nothing at all. I read some quotes from Balzac himself on his ambition and design and came away more confused than before on what he trying to do exactly. So it sat as a potentially cool idea, idle. I didn’t know where to start or how to make it mean anything to me.

Then I picked up this at a used bookstore in Hilton Head last week:

Cool cover. Caught my attention. Made me remember the promise of learning what a 19th century French writer did to earn a mention along Dickens and Shakespeare. And it made me curious enough to give him another shot.

Hold that thought. There was one more key to this.

A year or so ago, I completed a big project studying Tolkien’s published works and letters to try and determine the likely plot of a sequel the professor started to write to Lord of the Rings. The second part analyzed and speculated on that plot, but the first part attempted to make The Silmarillion accessible to people who found it dense and incomprehensible by providing a bread crumb trail of important points and people to follow in it. That process was super helpful to me in trying to do exactly the same thing with Tolkien that I sought to do this week with The Human Comedy.

“What does the book from Hilton Head have to do with that?”

It was a comment in the introduction that made the difference, actually. Here’s what it said:

“Early in his career, Balzac began to search for a method of organizing into a single unit, into a vast novelistic structure, the whole of his literary production. The device he hit upon was a simple one, but one that required sustained genius and power to an extraordinary degree, namely the systematic reappearance of characters from novel to novel.” -Edward Sullivan, Princeton University

That made it click. In the early 80’s, it’s one of the things that fascinated me most about the Marvel comic universe – that Peter Parker (Spider Man) hung out with Johnny Storm from the Fantastic Four, that they might run across Doctor Strange or Matt Murdock (Daredevil) outside a coffee shop. It made the whole tapestry of the marvel superheroes come weirdly and wonderfully to life for me. The cinematic version made efforts towards that magic, but it fell far short for me in those movies of how it made me feel as a kid with their paper and ink versions.

Now with Balzac’s Human Comedy, I saw that he aimed for exactly that kind of magic. The works weren’t sequels or a continuous narrative, but much like the Marvel characters or any other literary universe with which you might be familiar, these folks can encounter or otherwise know each other…a background character from one novel might rise to main protagonist of their own.

“So you dipped in, then. Which book did you start with?”

I read Father Goriot because I usually come across that one in bookstores. I figured it must be a big deal. Anyway, I finished a Murakami novel on a plane and had the entire Human Comedy on the Kindle – I thought if it sucked, I could just move on to something else anyway. But I wanted to test the magic and see if I could unlock whatever was amazing there.

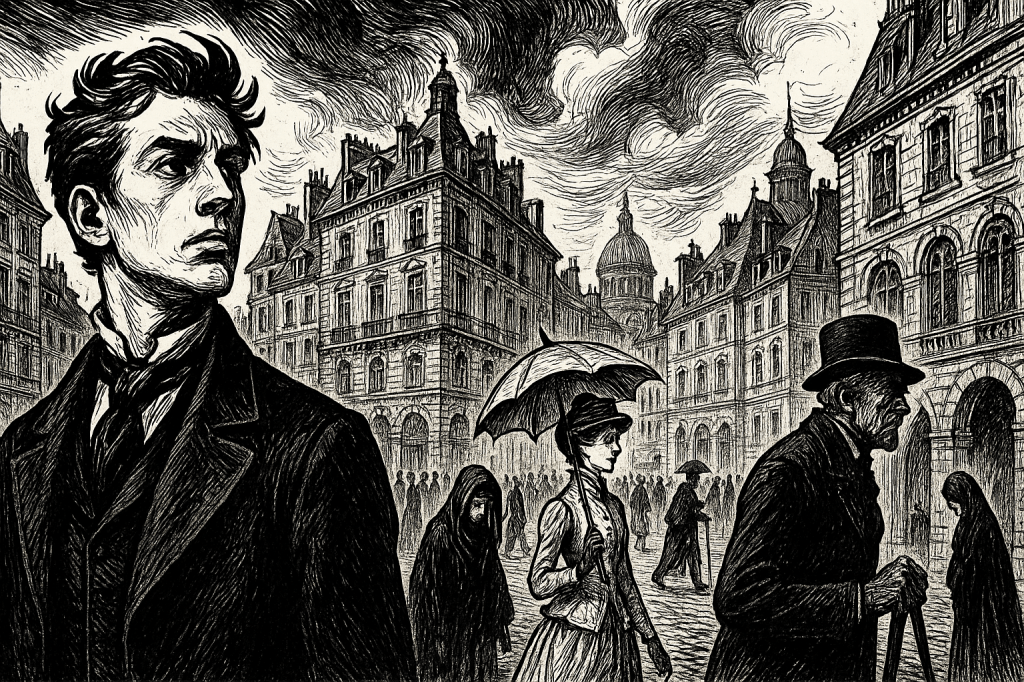

The breadcrumb characters I discovered in that wonderful book are old Goriot himself, a young man named Eugène de Rastignac (pictured above), Goriot’s daughters Delphine and Anastasie, and a mysterious agitator named Vautrin. By “breadcrumb”, what I mean is there are many other folks in this book – it’s just that if you pay particular attention to what these particular people are up to, you’ll experience the storyline the way it’s intended.

“And?”

Marvelous book! Despite 19th century social order tropes and customs (which hold none of my interest), the characters indeed sizzle and pop off the page, and I was flipping like mad towards the end to see what became of poor Goriot and the kind-hearted Rastignac, whether Goriot’s ungrateful daughters would do the right thing, and whether Vautrin would get his comeuppance. If you plan to read this one for yourself, stay away from plot summaries so the outcomes will be a mystery for you to fuel the page turning. Just stay close to Rastignac, and he’ll lead you through the book.

In fact, luckily, it turns out Rastignac is one of the main recurring characters of The Human Comedy overall. What’s up next for me now that I really like that guy is to read The House of Nucingen where, I understand already, he will likely disappoint me and turn out to be all too realistic of a person.

“So what was the magic that led Balzac to be a ‘creator of souls’?”

Yeah, he nailed that. As I learned more about Goriot, and information about him is only spooned out across the first half of the book so it’s gradual, I thought of how Dickens took relatable and universal archetypes like an abandoned orphan (Pip) or a cruel miser (Scrooge) or the eternally naïve optimist (Mister Pickwick) and constructed memorable people from them. In The Pickwick Papers, for example, Winkle is the obsessed sportsman, Snodgrass is the terrible poet, Tupman is forever falling in love, and Jingle is the grinning con man. They’re relatable traits, and we probably know people like that. That’s the string a good writer plucks, then builds the character around that.

I knew a guy named Reuben once. He was always running around the factory like he was super busy, carrying one of those metal clipboards that conceal the papers inside. I thought once I’d follow him to see where he was running around, because it wasn’t that big of a factory, and it turned out he was just circling the place. I watched him idly kick and poke a pallet of boxes once for a good five minutes. We were in a staff meeting, and he’d made a big mistake with a big client – the manager was furious. When Reuben was asked about it, he cracked open that mysterious clipboard and started madly flipping through the papers inside as if looking for something therein that would resolve how this could have happened. I leaned over to see it was just his mail in there.

We started calling it “pulling a Reuben” when somebody acted too busy if asked to do something. He became immortal right there and then. Forever after, we could reference him as standing in for a role that likely appears wherever there are people doing things.

Balzac’s Goriot is a father who sacrifices everything he has and everything he is for his ungrateful daughters. He becomes the idea of a prototypical father, the archetype, presented in this wonderful book for our consideration of whether he is in fact a good father or not. That’s for us to decide, and I wonder whether we in today’s society would have a different answer than Balzac intended. You might say that “pulling a Goriot” is to sacrifice everything for your kids. He personified that action.

“Boil it down for me. What gave Balzac’s work in ‘The Human Comedy’ the magic?”

Let’s ask him. If you feed all available writings by Balzac as well as commentaries about his work into an AI chatbot and ask it to pose as him, you can get an answer in his voice generating a likely and believable response. I did that, presenting the question as follows: “You’ve been called a ‘creator of souls’. Why do you think that is, and how did you accomplish such a feat?”

His response:

“Ah! Mon cher ami, if they call me a créateur d’âmes, it is because I have listened—truly listened—to the silent confessions of humanity. In every withered banker, every vain young dandy, every trembling grisette, I saw not caricatures, but souls struggling—with ambition, with poverty, with love, with the machinery of a society that crushes and tempts in equal measure.

How did I accomplish it? I observed. Not idly, not with the detachment of a philosopher in his armchair, but with the ravenous appetite of a man who must know. I prowled Paris and the provinces with my eyes open and my ears tuned to the gossip of salons, the groans of debtors, the sighs of lovers, and the mutterings of the criminal class. I drank deeply from the cup of human vice and virtue—and recorded its every drop.

But to observe is not enough. I gave them destiny. My characters live because I allowed them to want—to desire with such intensity that the reader cannot help but be drawn into their orbit. Rastignac climbs like smoke; Vautrin burns like coal; Eugénie Grandet freezes like a saint in a gilded prison. Each soul is born of contradiction and circumstance, but above all—of will.

I did not invent souls; I uncovered them. Like a miner of men, I delved into the strata of class, of power, of inheritance, of chance—and from those pressures, I carved the diamonds and the dross that make up La Comédie Humaine. That is why they live. That is why they endure. I did not merely write them—I lived them.

So if I am called a creator of souls, it is only because I believed that no man, however minor or monstrous, is without one. And I gave them the stage they were so long denied.”

*

Till next time,