Some glorious times when you troll around in old journals and historical accounts, you come across an adventurous soul of long ago that made the absolute best of truly magical opportunities, braved unbelieveable dangers, and came out on top.

I’ve got one for you today that became an obsessive research project ultimately leading to a road trip, locals in a town library gathering around the table with me, and a moment of awe (for me at least).

Welcome back to an ongoing series we call…

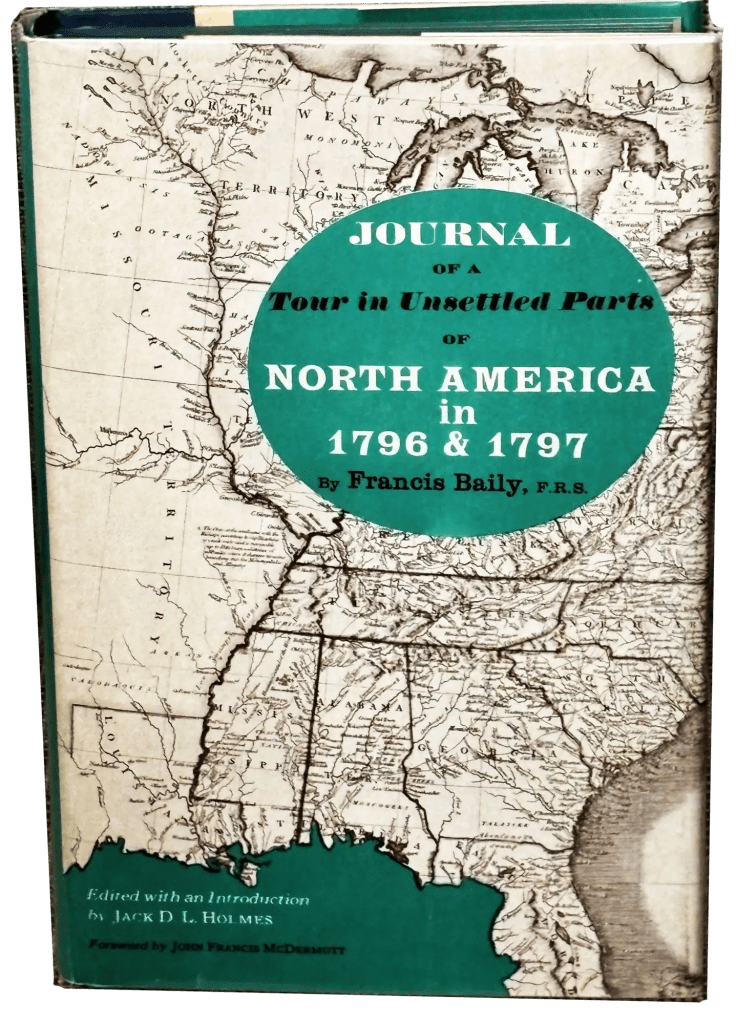

I went into my study a couple of weeks ago looking for something to read. It’s a lifetime of books collected in there, so there was no telling what I would pick up. I grabbed one titled Journal of a Tour in Unsettled Parts of North America in 1796 & 1797 by a guy named Francis Baily. Here’s a copy for free.

What’s interesting about that?

Baily was 21 years old, and for reasons he never gave, he came over from England for 2 years and visited an America that was brand new and wide open. What this guy was able to see and do in those 2 years was incandescent. It was an opportunity of a generation to go where he went, and Baily made it happen.

He landed in Norfolk, visited Baltimore and Philadelphia, describing them wonderfully such that you could all but see them in your mind’s eye. He described the road from Lancaster to Philadelphia as “paved with stone the whole way, and overlaid with gravel so that it is never obstructed during the most severe season”. Little nuances like that just popped for me – like the little museum in Philadelphia founded by a “Mr. Peale” which had just opened. I fell into the habit of leaving ChatGPT on voice mode so I could ask it as I read what became of some of the things Baily saw and people he met. (Peale’s collection got busted up later and distributed to places like the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.)

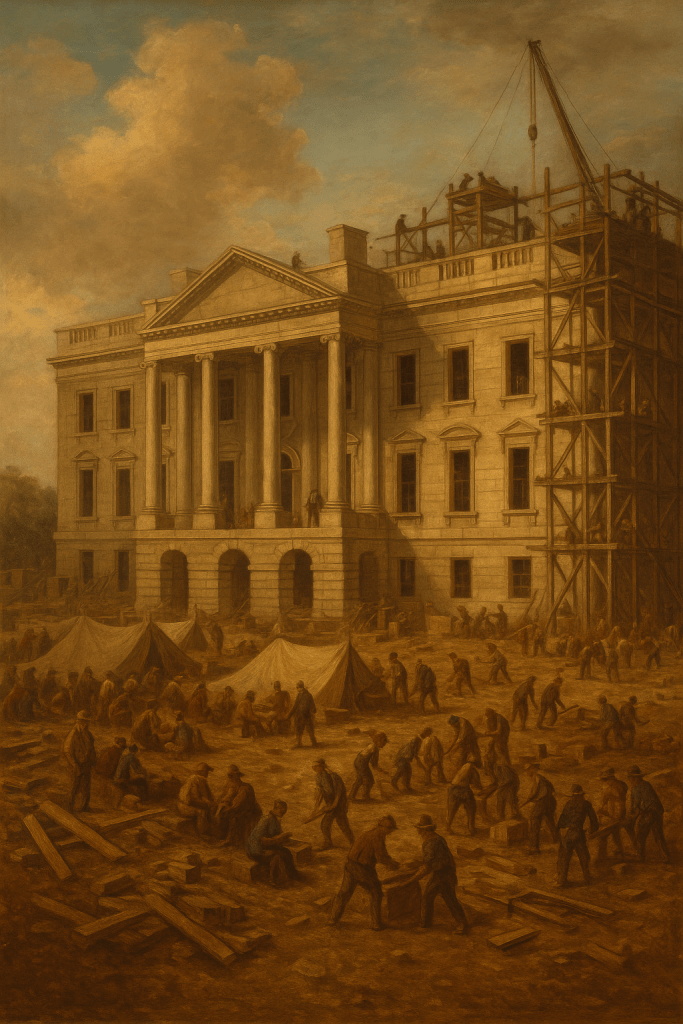

He visited “the new city of Washington” where his “first walk was to the President’s House”, which was to be the White House and was still under construction. Of Washington itself, he said “not much more than one-half the city is cleared; the rest is in woods; and most of the streets which are laid out are cut through these woods” Also, “The canal and the gardens, as well as bridges, which you see marked down in the plan, are not yet begun”. And finally, “Game is plenty in these parts, and what perhaps may appear to you remarkable, I saw some boys who were out a shooting, actually kill several brace of partridges in what will one of the most public streets of the city”.

He went to New York and said: “…it is an irregularly built place, consisting principally of little narrow streets, though some of those which are newly laid out are broad and handsome, particularly Broadway, extending nearly a mile in length.” You see something like (explaining why it’s called ‘Broadway’), then he says “The inhabitants of New York are very fond of music, dancing, and plays; an attainment to excellence in the former has been considerably promoted by the frequent musical societies”. I mean…Broadway….in 1796. Music already. Crazy!

Honestly, I marveled at every little inn or hut where he stayed as he described the meals, the ramshackle rooms, sleeping in a drafty barn with a smile on his face at what he was doing. I hadn’t read two chapters of this before I really, really liked this kid.

Okay, that does sound fun. But you mentioned a shipwreck site?

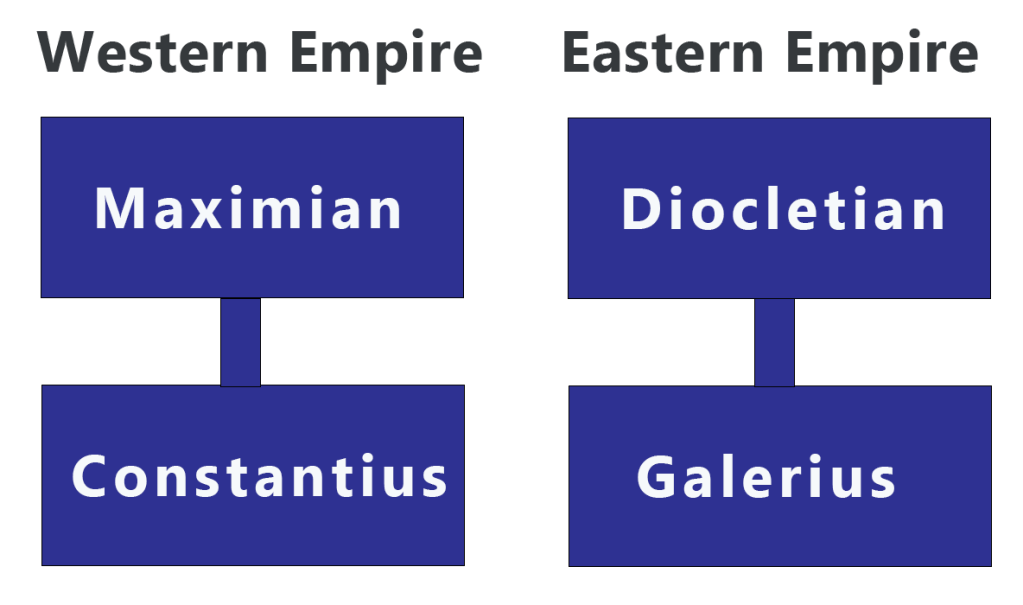

Right. Baily’s adventure really picked up once he left Pittsburgh on the Ohio River headed Northwest at first, before ultimately bending south. He’d booked passage with some people looking to found a new settlement, specifically a friend he’d made named Samuel Heighway who’d purchased some land in modern-day Ohio off the Little Miami River and was trying to get there with some agricultural equipment and a handful of settlers. Why was Baily accompanying them? Who knows! He just did, and it wound up awesome.

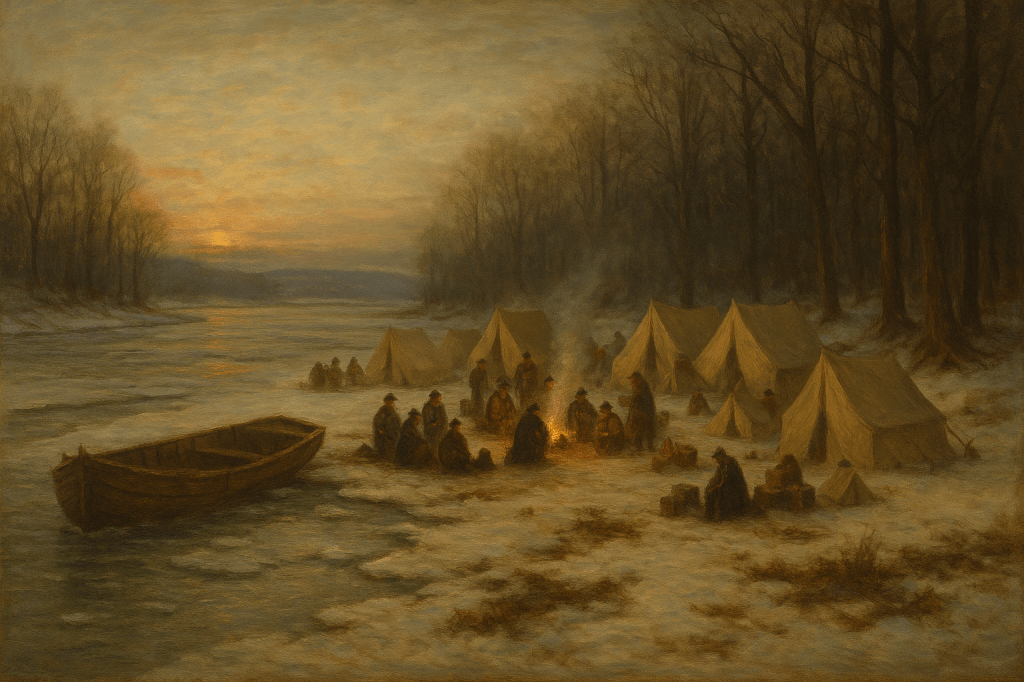

We need to keep in mind that American rivers in 1796 were crazy dangerous and nothing like the placid, dammed wonderlands they are now. At this point in the tale, it was a cold December with the Ohio half-frozen with ice blocks as big as houses sailing past at great speeds.

Dec 21, 1796: “We were awakened out of our sleep with a noise like thunder, and, jumping out of our beds, we found the river was rising, and the ice breaking up. All attempts would be feeble to describe the horrid crashing and tremendous destruction which this event occasioned on the river. Only conceive a river near 1,500 miles long, frozen to a prodigious depth (capable of bearing loaded wagons) from its source to its mouth, and this river by a sudden torrent of water breaking…Conceive this vast body of ice put in motion at the same instant, and carried along with an astonishing rapidity, grating with a most tremendous noise against the sides of the river and bearing down everything which opposed its progress – the tallest and the stoutest trees obliged to submit to its destructive fury!”

Should you decide to read this marvelous book, I won’t steal from you by describing all that happened to them at that spot in the river. I called it a shipwreck, though. Remember that much at least.

Dec 25, 1796: “Here am I in the wilds of America, away from the society of men, amidst the haunts of wild beasts and savages, just escaped from the perils of a wreck, in want not only of the comforts, but of the necessities of life, housed in a hovel that in my own country would not be good enough for a pigstye, at a time too when my father, my mother, my brothers, my sisters, my friends and acquaintance, in fact, the whole nation, were feasting upon the best the country could afford. I could not but picture to myself the fireside of my own home…”

Despite incredible danger from drowning, frostbite, starvation, and exposure, it was also on Christmas day that Baily wrote one of my favorite quotes of the entire book. Keep in mind the conditions he was under as he wrote this:

“…there is something so very attractive in a life spent in this manner, that were I disposed to become a hermit, and seclude myself from the world, the woods of America should be my retreat; there should I, with my dog and my gun, and the hollow of a rock for my habitation, enjoy undisturbed all that fancied bliss attendant on a state of nature.”

Ultimately, they constructed another boat and got underway again in February after an unforgettable winter at that lonely place on the Ohio.

You didn’t find the site of that shipwreck, did you?

It wasn’t easy, but yes – I absolutely did. The girl at the Barnes & Noble counter who sold me a map of West Virginia asked me if I was doing some traveling. When I told her what I was looking to do – collect and trace the little clues Baily noted in his journal and leverage ChatGPT and the map to find the exact spot – she only said with eyes widened, “That sounds amazing!”

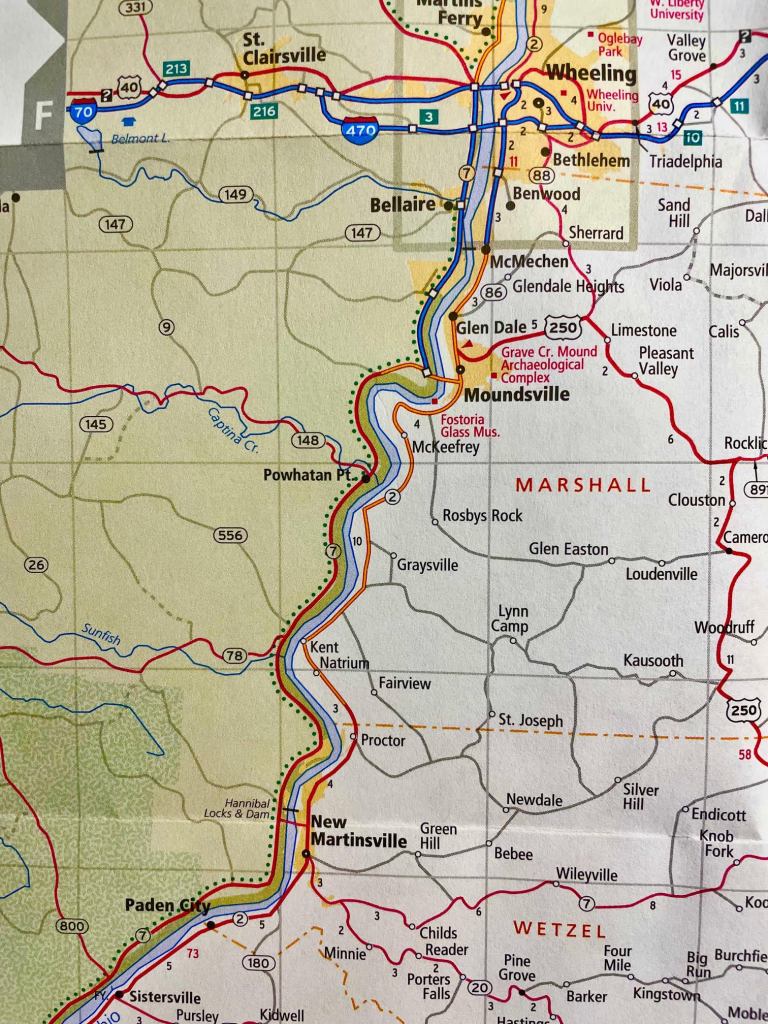

We’re talking 228 years later, with few proper names provided – and the ones that ARE provided are rarely in use today. What this looked like for me, as I was on a business trip out of town doing this, was me in a Doubletree late at night leaned over the map poring over Baily’s account and tracing any likely touchpoints with my finger, asking ChatGPT as if in conversation things like “He mentions Capteen Riffle, south of Grave Creek – what would that likely be referencing?” To which I would receive answers such as “That likely refers to modern-day Captina Island, across from Powhatan Point, Ohio.” Knowing that AI is wrong as often as it is right, I fact-checked in Google along the way to confirm each touchpoint.

- He “got fast upon a riffle near Brown’s Island” near modern Weirton, WV

- He passed “Buffaloe Town”, which is modern Wellsburg, WV

- He went aground 1/2 mile above Wheeling (still exists!)

- He put ashore near Grave Creek (near modern-day Moundsville, WV)

- He passed “Capteen Riffle” near Powhatan Point, OH and claimed he made 9 miles that day to “Fish Creek” near modern-day Martinsville, WV. That bad estimate of his pained me somewhat later.

- He put ashore at a plantation recently built by an Irishman named Daily (no later records), and was told the river was entirely frozen.

- Baily and Heighway walked “about 5 miles” down the banks of the river to Fish Creek, meaning Daily and their boat (at that time, though not the final shipwreck site) were 5 miles upstream of Fish Creek (and his 9 mile estimate was wrong). 5 miles upstream of Martinsville is modern-day Proctor, WV. That’s where Daily’s plantation was.

- Baily and Heighway went back to Daily’s after seeing that indeed, the river was frozen solid at Fish Creek and took the boat downstream to a safer place the next day, saying it was “about a mile to a place which we had observed yesterday on our walk, and which we conceived more secure from the bodies drifting downriver from the one we were in”.

Whoa. We don’t need that kind of detail. Just say what you know and how you know it.

Look at that sharp bend in the river just south of Proctor, about a mile down in fact. Here it is on Google Earth:

Remember how he described the ice blasting down the river. Imagine the eddies and more stationary water just past that bend, and using the trees and shoreline of the bend itself to weather the incoming debris and ice. It makes sense that they would see the area with trees now on the southern shore, northeast of the buildings you see in Proctor and across from the Long Ridge power station on the north as safer than staying at Daily’s plantation upstream where the river was straighter. Baily reported that Grave Creek (Moundsville) was ~9 miles upstream of where they were moored, so that aligns with the site being very close to Proctor.

No, this is the place. If I’d been close enough, I’d have driven there to take a look. I chuckled and called my dad I was so excited!

You mentioned a town’s founding?

At one point, they have to leave the river and hire wagons to make it “between forty and fifty miles off” where the land Heighway had purchased “lay for the most part amidst a desert wilderness, where no wagon had ever approached”. Baily described his time with Heighway:

Mar 7, 1797: “The town he had laid out at right angles, nearly on Penn’s plan, with a square in the middle, which he told me, with a degree of exulting pride, he intended for a courthouse, or for some public building for the meeting of the legislature; for he had already fallen into that flattering idea which every founder of a new settlement entertains that his town will at some future time be the seat of government. He also described to me, and walked over, the ground where he intended to make his gardens, his summerhouse, his fishpond, his orchard…” Continuing, “I believe he was as happy as if he saw them all before him. Whereas, for myself, I could behold nothing but a wild uncultivated country, full of lofty trees and prickly shrubs; and when he showed me fishponds and his serpentine walks, I could only discover a little standing water, and a few deertracks.”

That bit absolutely fascinated me: to see the very image of a town’s founder in the very first days, with only survey sticks in the ground, and the men who’d just climbed off the wagons with him taking axes to trees to build the first houses, and the founder laughing as he walks his imagined town.

I googled Samuel Heighway and found that his town became modern-day Waynesville, Ohio. Since I wasn’t too far from Cincinnati at the time, I checked Google Maps to see how far the drive would be.

And you drove there?

Yeah, I had to. I was getting too excited about all this. That Baily was inspiring me.

And?

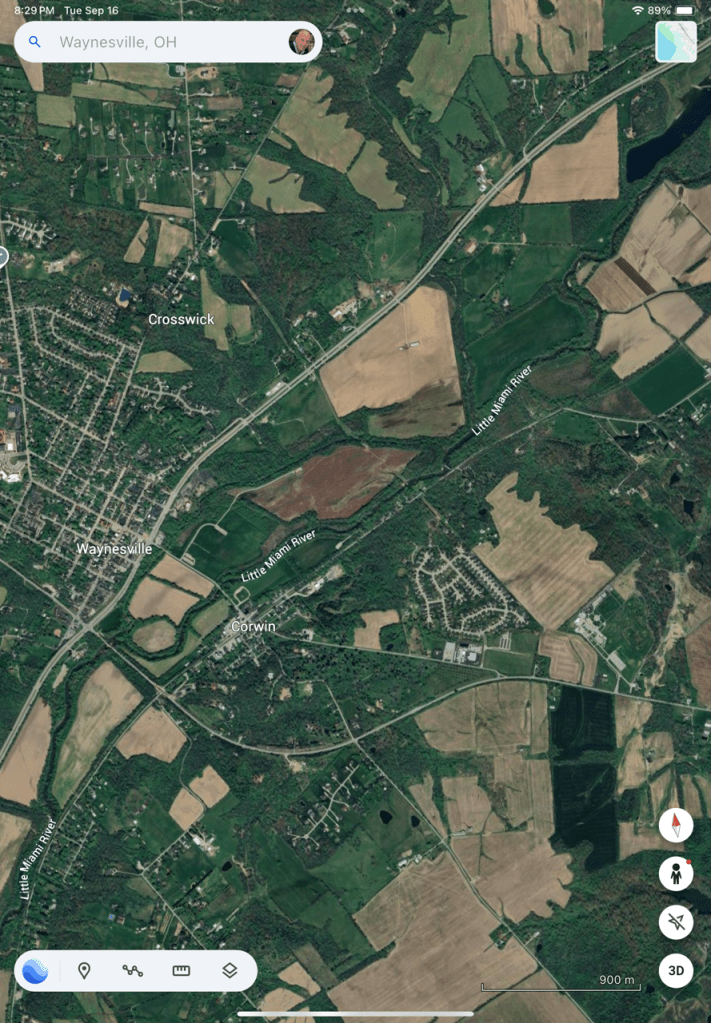

Just a little town. Nice, actually. I walked from one end to the other trying to get a feel for where these guys would have been walking…where they would have laid the first buildings. It looks like this on Google Earth (Waynesville):

I tried the Chamber of Commerce to see who managed the historical markers, to see whether there was a town historian or something. They directed me to a town historical archive in the Waynesville library. The wonderful librarians there had a similar reaction to the girl at Barnes & Noble, and I gathered a bit of a crowd telling them the story I was researching. My objective, as I told them, was to find the very spot where these men stood as they first laid out the town.

One of them ran to the back computer promising to find something. Another gave me an exhaustive tour of the archives and started pulling various items off that might be helpful. Really, those ladies were fantastic.

I found this:

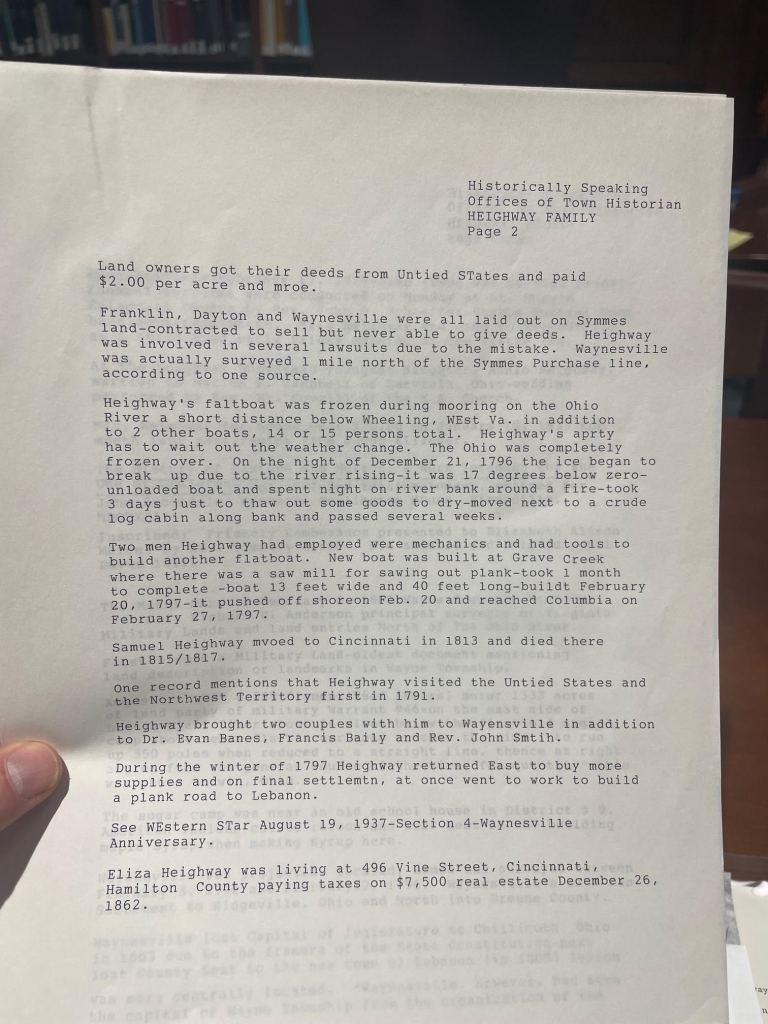

That broke my heart a little. Heighway didn’t stay, and in fact moved to Cincinnati in 1813 and died around 1815.

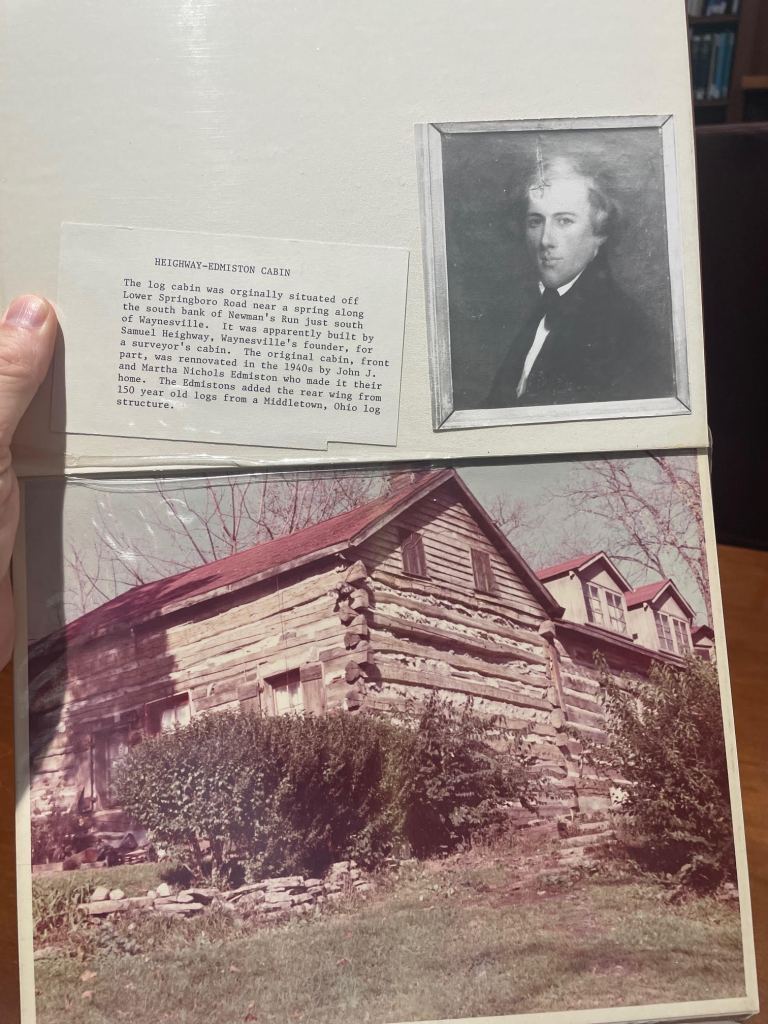

Also found this, an actual cabin Heighway built:

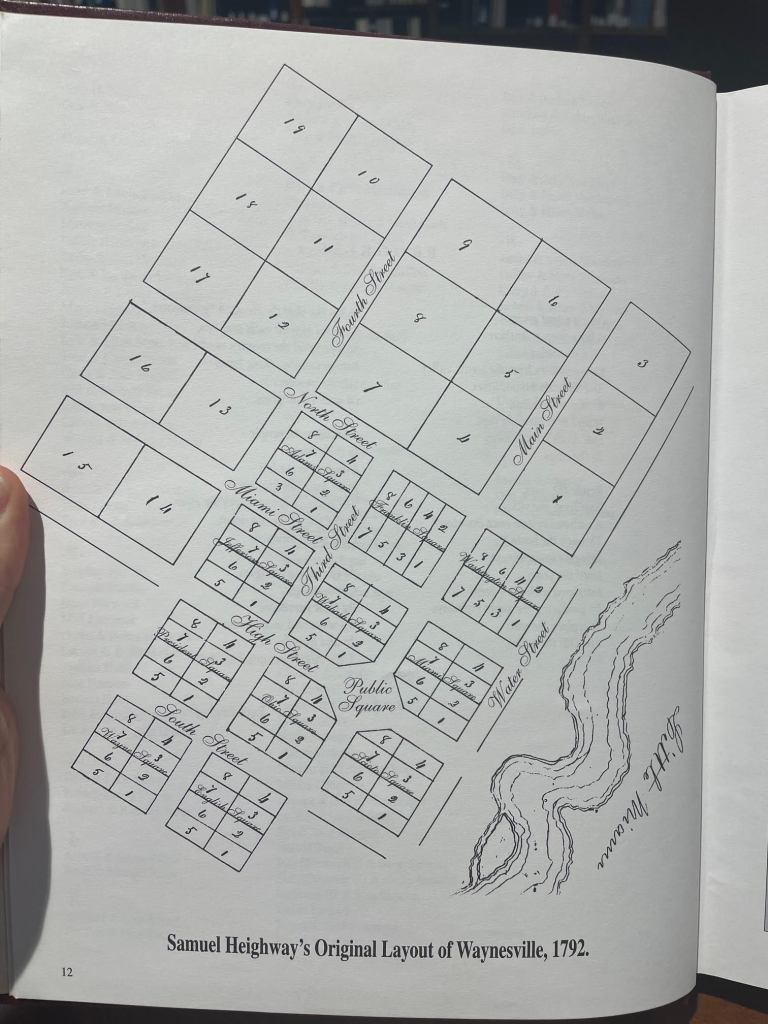

But what helped the most was this:

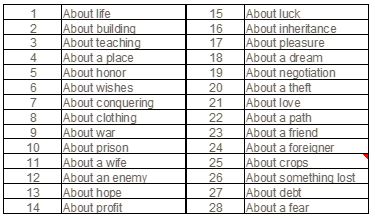

It’s a reproduction of Heighway’s original plan for the town: the one he showed Baily. Check how close the buildings are to the Little Miami River, and the fact that the first street was called “Water Street”. I saw Main Street on the map, and modern-day Waynesville is just up the hill from the river with a big old Main Street now. If that’s the same Main Street location, then where in the world was “Water Street”? I hadn’t seen it before I came to the library.

I took the plan back to the librarians and asked them what they knew about Water Street. An older lady who was sitting with them heard me and leaned back, thinking, “Water Street? We used to have a Water Street. That’s where the old mill was.”

The old mill? That sounded promising. “What happened to the mill?”

“Oh, they tore that down when they built the new highway.”

“You’re killing me. That’s what I’m looking for. I’m sure of it. Where would that have been?”

She pondered, scratching her chin maddeningly, “Oh, that’d be down in Corwin.”

I thanked everybody and blasted back to the car to drive down hill and across the river. I say “river”, but it looks like this now:

At one point, it clicked for me, stepping out of the car right across the Little Miami from Corwin and into a cornfield, why Waynesville is where it is up on the hill. The river would have flooded over the years, so they moved to higher ground. Main Street is just up the road. The plan showed Water Street and the first buildings right where I was standing.

Here:

I can’t tell you that’s the precise spot where Baily chased behind Heighway as they laughed and joked what would become of the land, amid the hammering and axe chops.

But it sure felt like it to me.

Till next time,