Last week, I took a road trip down the Mississippi Blues Trail out of Memphis. It was incredible, and I might write that one up as well. Seriously, we ate at the Hollywood beside the piano where Mark Cohn was inspired to write “Walking In Memphis”, saw BB King’s famous Lucille guitar, and walked Dockery Farms where the Delta Blues were born. Amazing trip.

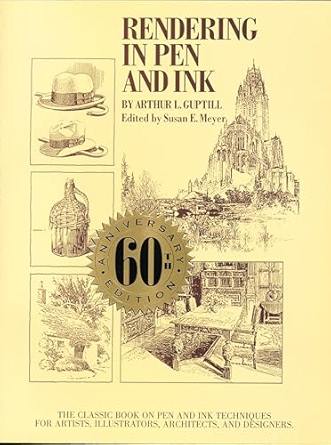

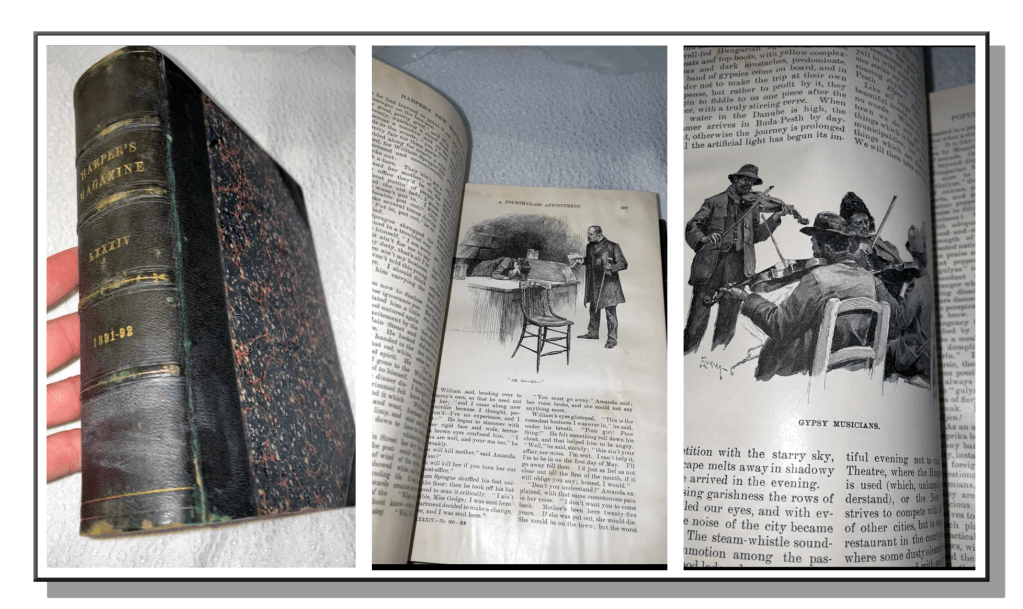

The only reason I mention it now though is we were headed back on a route through Little Rock and back to Kansas City when we stopped at an old antique mall. If you’ve hung around here at Grailrunner before, you well know how much we’re into old bookstores and the forgotten but mind-expanding wonders you can find on dusty old shelves. And man, have I got one for you today!

This guy here. Smash the image below for a short video showing what I mean.

It’s a hardback compilation of Harper’s Magazines from 1891 through 1892. Harper’s is a monthly magazine covering culture, finance, literature and the arts that was launched in 1850 and is still continuously published today. I didn’t have any particular fondness or interest in that magazine so much as just seeing what people read about in the 1890’s. I’m also a little obsessed with the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, also known as the Columbian Exposition, and I was hoping there would be a mention or two in here, and there was.

That’s why I first picked it up.

As I flipped through the pages, I was stunned by the quality and craftmanship of the pen & ink and engraved illustrations inside. I use the word carefully…stunned! Some of the artists were familiar to me, but for many of the pieces inside, I couldn’t even tell who the artist was. Credits weren’t always given, and signatures were too stylized to read.

I used ChatGPT to analyze some of the more interesting works to research the artist when it wasn’t obvious, and it was surprisingly useful for that. Often wrong, but with some caution and follow-up research, you can usually zero in on a likely name.

Thought I’d share some of these beauties with you today, and maybe introduce you to some wonder-workers of the past who could summon sparkling magic with a simple fountain pen. I’m offering 20 vintage illustrations here for admiration and craftmanship study.

Care to join me?

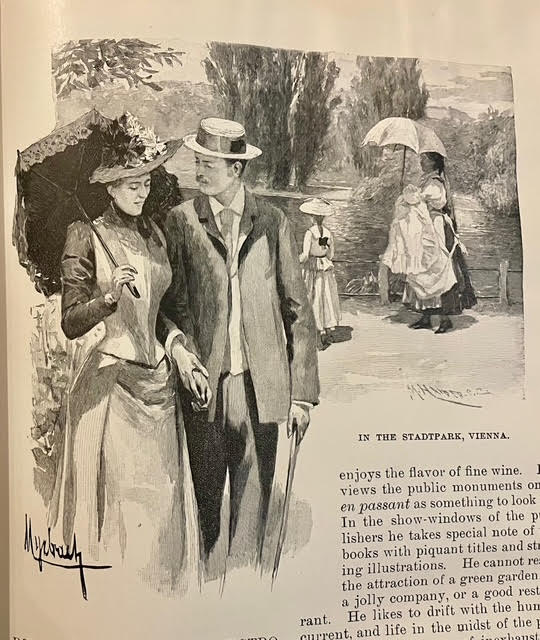

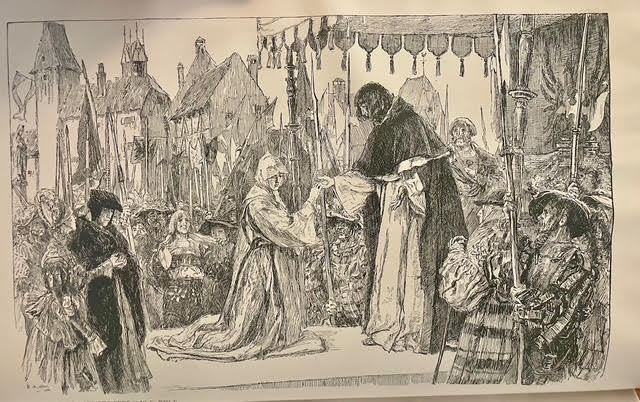

Myrbach was an Austrian-born artist and leading illustrator of the 19th century. Also acting as director of the Vienna Academy of the Fine Arts, he was known for detailed illustrations of military scenes and historical costumes. This image struck me with its sense of depth, balance of light and shadow, and elegant washes. Looks like it’s coming out of the page.

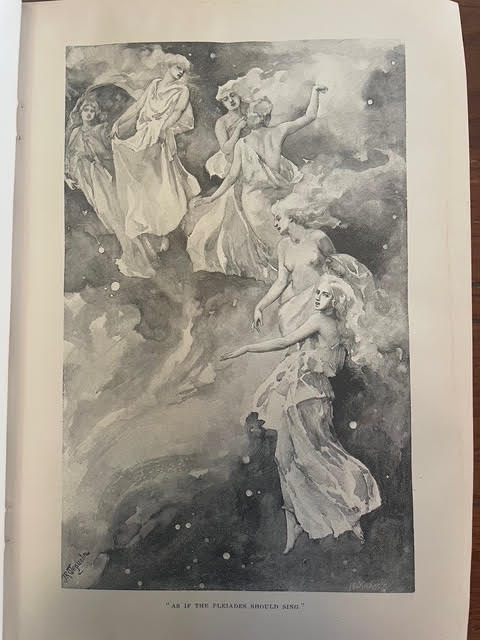

I loved the subject here, and the haunting feel of it. The artist was J.R. Weguelin, who was primarily known for his dreamy watercolors and oil paintings, though he supplemented his income by slumming to draw masterpieces like this one for magazines.

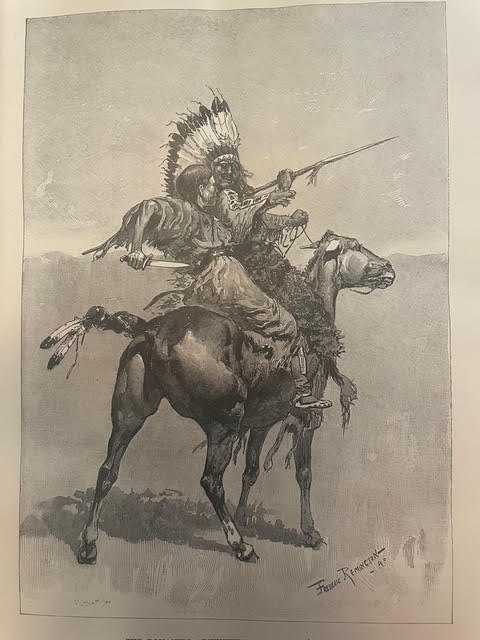

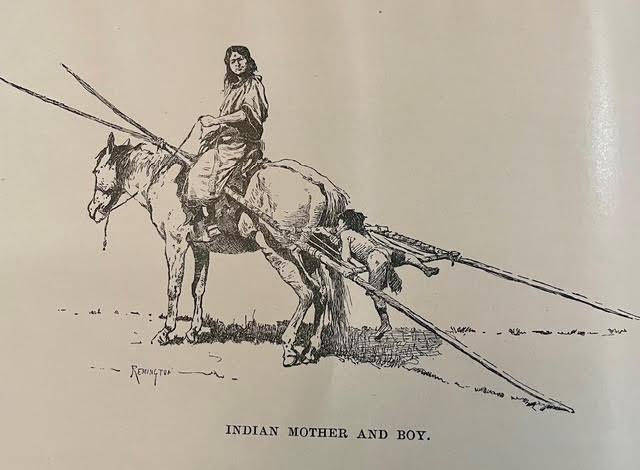

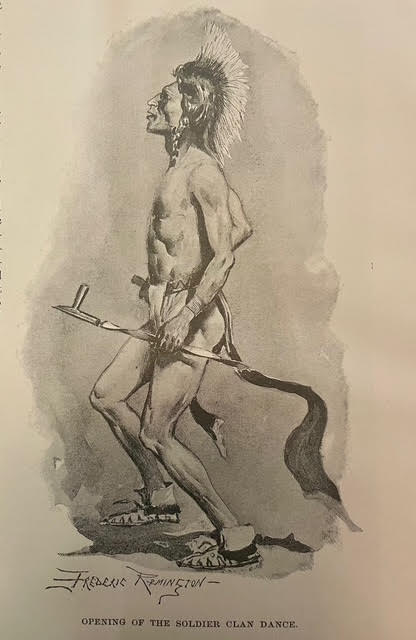

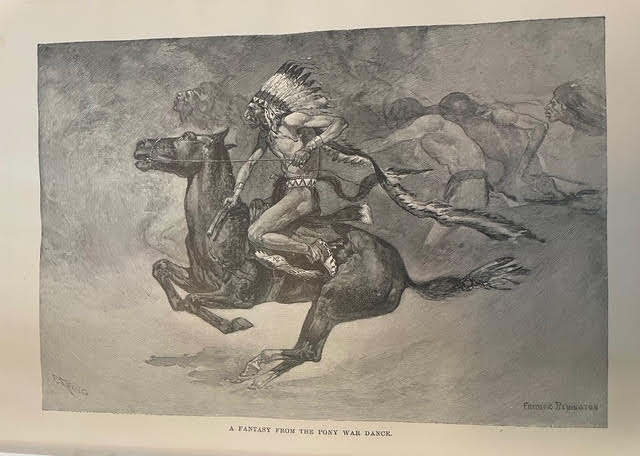

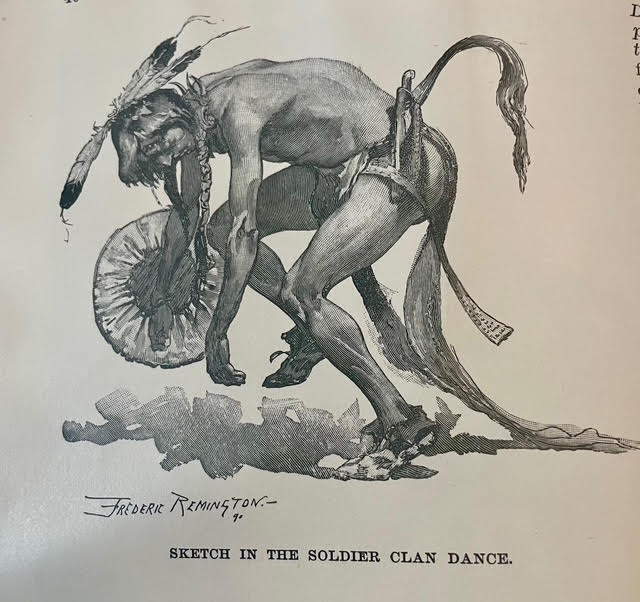

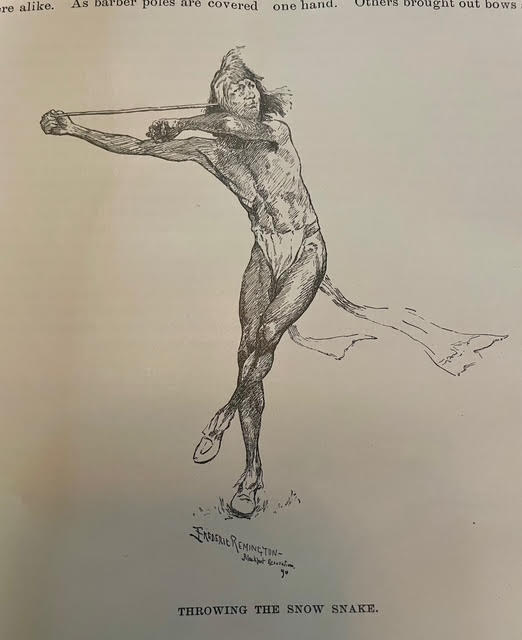

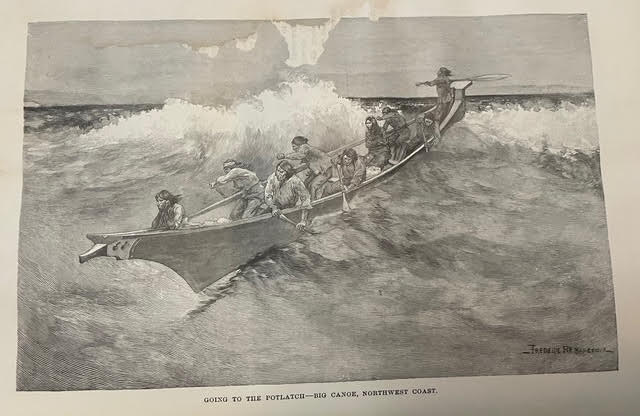

When I came across a simple article about Native Americans, I couldn’t believe I was seeing an original Frederic Remington illustration there just as a picture for a magazine. Then another. And another. These seven images are all by Remington, and they’re all beautiful. He was known for paintings and drawings mainly depicting the American west.

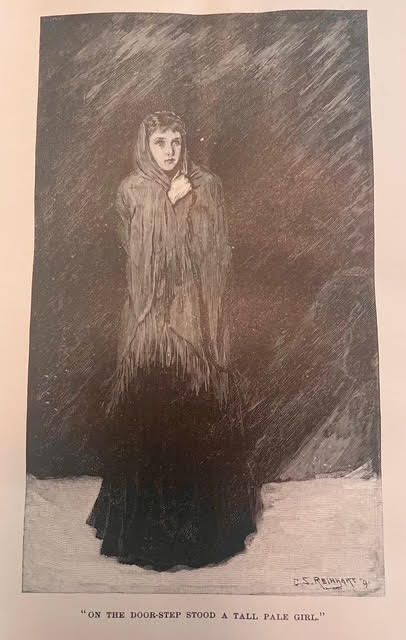

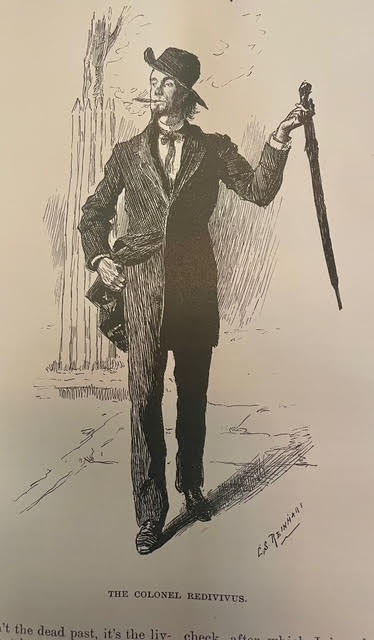

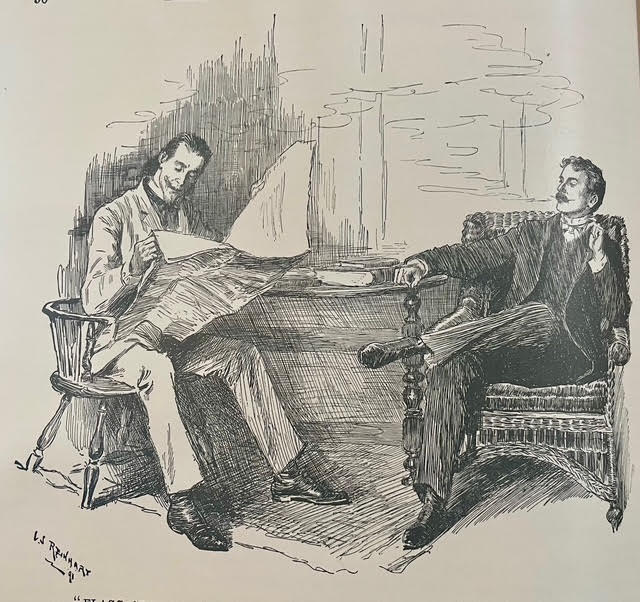

These three were all by Charles Stanley Reinhart, an American painter and illustrator who was also responsible for artwork on certain silver certificates commissioned by the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing said by many to be the most beautiful monetary designs ever produced by the United States. That last image, of the two guys sitting and smoking is an absolute master class in pen & ink linework. I struggle in my own drawings to avoid outlines, to use contrasting light and dark for the silhouettes, and to choose the right directions for hatching that don’t distract from the shapes and mood. Reinhart entirely nailed it with that one.

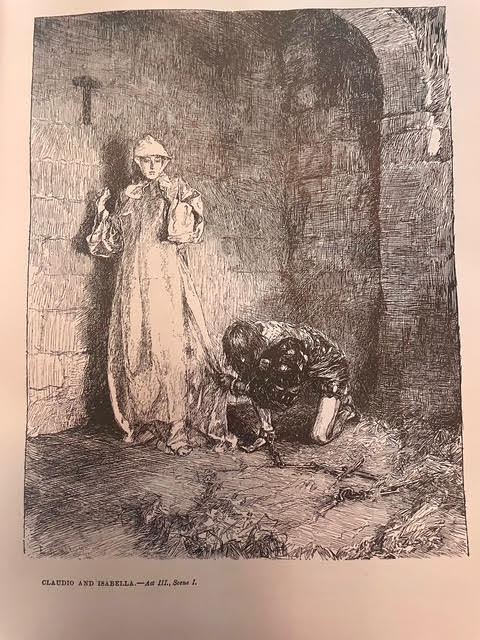

These two were by Edwin Austin Abbey, an American muralist, painter and illustrator known most for Victorian and Shakespearean subjects. Perhaps most dear to our hearts at Grailrunner, Abbey was the artist behind the famous “Quest and achievement of the Holy Grail” murals at the Boston Central Library.

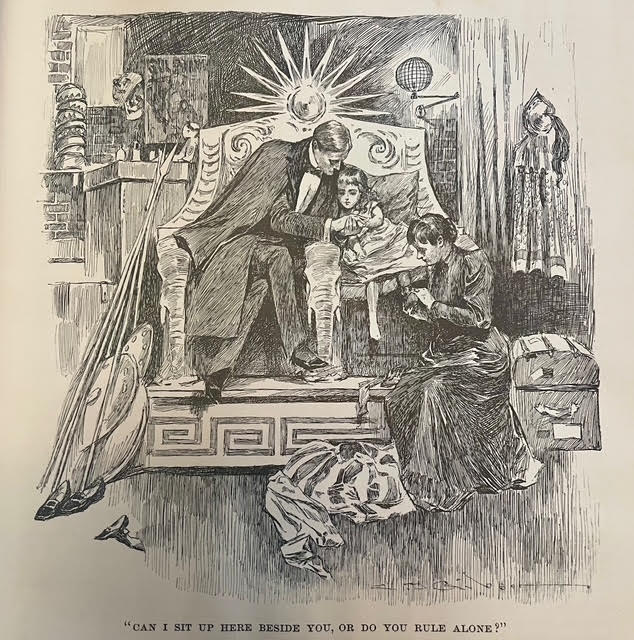

I really loved these two, as they independently stuck out for me on their own merits before I realized they were by the same artist and in fact, an artist whose work I thought I knew. Charles Dana Gibson was an American artist typically cited as being the creator of the “Gibson girl”, the iconic representation of the independent American woman at the turn of the 20th century. I think that puts the poor guy in a box that is unfair, as his composition, linework and hatching are among the finest of his age. He did a little more than ads with girls in them. Seriously, these two images are firecrackers!

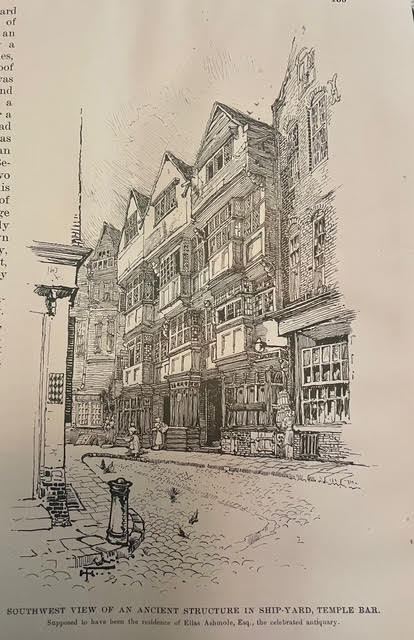

These two architectural pieces just made me stare in awe. I can’t draw buildings, no matter how careful I am. They always turn into heavily lined, overly simplified, often leaning, caricatures of buildings. Not my thing, unfortunately. But these two by John Tavenor-Perry (at least I think so) are masterworks. ChatGPT couldn’t do anything with that weird signature (looking like a stylized rune but supposedly initials). After some heavy back-and-forth, I think we landed on a likely artist though I’m open to correction.

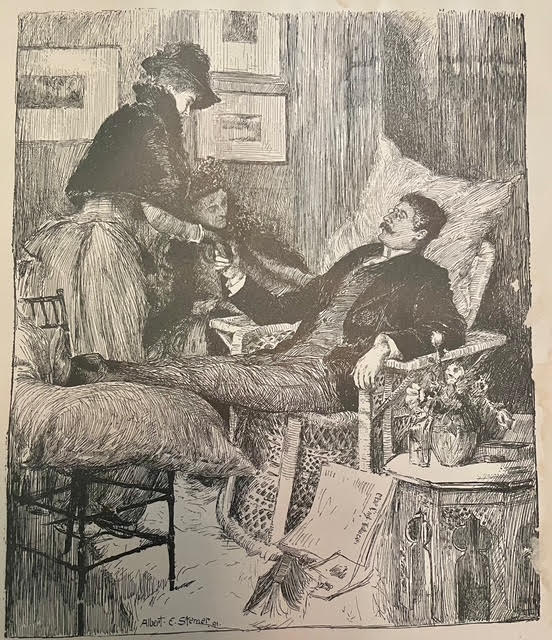

By Albert Sterner, this piece is a treasure-trove of hatching. I love it. Somehow, he’s managed to keep all these disparate elements in the composition cleanly segregated: the ladies and the cushion, his legs and vest, the flowers, the chair, shadows…all of it clearly silhouetted and easily read despite being a jumble of things. No way could I have figured out how to get all that detail into a drawing without feeling I needed to strip it way down so you could tell what it was.

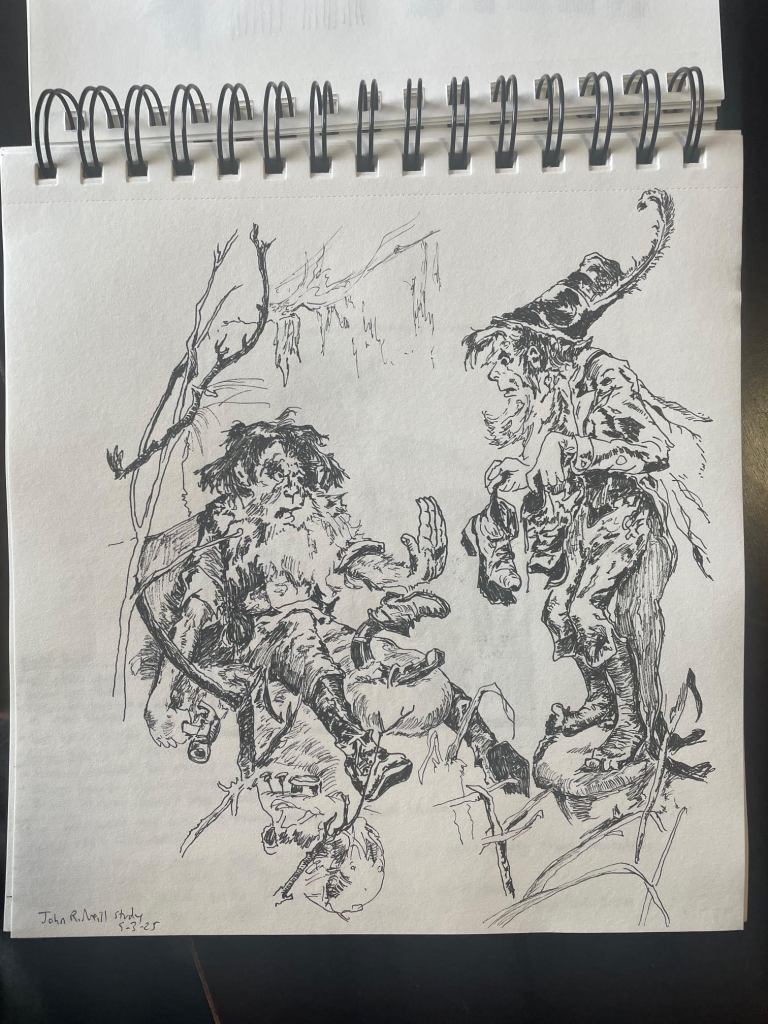

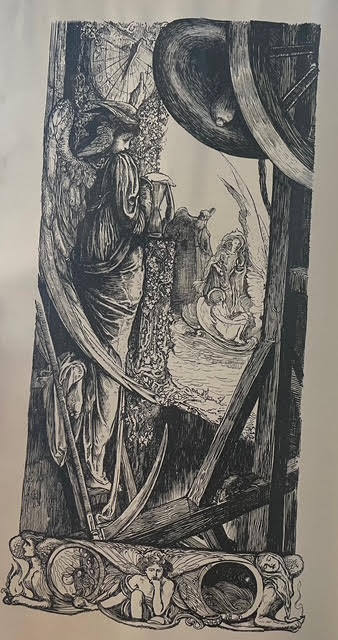

And now finally, the mystery piece.

This one.

I was mesmerized. It accompanies a poem by James Russell Lowell titled “His Ship”, appearing in the December 1891 issue of Harper’s Magazine. No credit given anywhere, including the “Editor’s Drawer” where many other attributions for illustrations are provided.

The signature is maddeningly concealed in the drawing. I think. Hard to say if that’s a signature or not. Here’s what I mean:

Anyway, I contacted Harper’s in case somebody’s maintaining an archive of some kind to help identify the genius who did this. It’s gorgeous. If I get any kind of response or make headway on the identification, I’ll come back and update you.

*

But that’s what I wanted to bring you today. Masters of their craft in the golden age of illustration, doing what they did and generating timeless works of art. For whatever reason, and not just as an aspiring artist myself, these drawings are unearthly and hypnotizing to me.

What do you think?