I’m told my reading habits are a little out there. I get that. I do.

However, it intrigues me that in almost any field of human endeavor, there is a specific type of personality that thrives on breaking its rules and forging incandescent new ways of doing things. If you’re new here, that’s almost entirely what we do here – find, spotlight, analyze, and celebrate innovation in the creative process.

So I was reading this book about 1960’s beach music:

I don’t like that sort of music at all. I especially detest men singing falsetto and lyrics obsessing over the teenage emotional range. However, I had heard that the Beach Boys album, Pet Sounds, was considered the greatest and most influential album in music history. Knowledgeable people say that. I wanted to understand why in the world that would be, given its niche genre, its terrible album cover and name, and the fact that it isn’t chock full of top 10 hits.

What was so special? And once I knew that, I would of course ask: what inspired it?

I’ll cut to the chase since the answers to those questions don’t actually comprise my point today. I want to extend some of these lessons over to mythmaking and storytelling since that’s my main jam. (If you’re into this crossover of music and storytelling, I wrote about this sort of thing in an article called “Aesthetic Puzzles: When Bach Met Shakespeare”, which you can go catch here.)

Why is Pet Sounds a big deal?

Brian Wilson was the main creative driver behind the 1960’s-era pop band, the Beach Boys, and took a break from touring in 1965 to focus on creating “the greatest rock album ever made”. Till then, their songs were bubble-gum melodies of no real sophistication and lyrics aimed like a piledriver at teenagers having fun, especially in and around the rapidly-growing fad of surfing. Wilson was enamored with the “wall of sound” production techniques of music producer, Phil Spector, which involved using echo chambers and physical studio arrangements augmenting studio manipulation of recorded tracks to generate robust, layered textures of sounds that would come across richly on a jukebox. Spector’s stated logic behind his own innovation was:

“I was looking for a sound, a sound so strong that if the material was not the greatest, the sound would carry the record.”

So it was mono (versus stereo) playback technology and the limited fidelity of speakers available at the time that prompted Spector to layer sounds together and experiment with ways of making the sounds more textured. Wilson felt the Beatles album, Rubber Soul contained some of the most mature lyrics yet for the band, and from these two launch points, he wanted to get more emotional with his lyrics and more experimental with his production techniques to surpass them all.

Wilson wound up innovating in all areas, and indeed developing intriguing ways of making the studio itself an instrument: combining, for example, multiple instruments simultaneously into a blended and new quality that sounded nothing like any of them. He introduced novel instruments like bicycle bells, a variation on the theremin, among others, in a rogue recording marathon of studio musicians while the actual band was out touring. Nobody had done that before, or even went off the trail of a small ensemble like that to make an album that couldn’t actually be played live. He also experimented with chord voicings, meaning how different chords are brought together (a little out of phase, for example, so there’s a slightly noticeable tremor) or avoiding a definitive key signature. By all accounts, Wilson’s efforts with the band surpassed anything Spector had done or would do. He took the inspiration and ran with it.

Studio musicians involved said of the time that they knew something very different was happening. Something important. It was interesting to me, reading what it felt like for the other guys there, the ones just hired to do a thing and realizing they were part of something.

So the idea to hold in your head then, for my point to land, is this: an approach towards recording music where all manner of frequencies and qualities of instruments and voices are layered over each other in a rich texture of sounds that you could listen to a multitude of times with headphones on and the volume turned up and still catch new things.

Texture. That’s the thing to remember. Innovating with texture.

What’s all this got to do with storytelling?

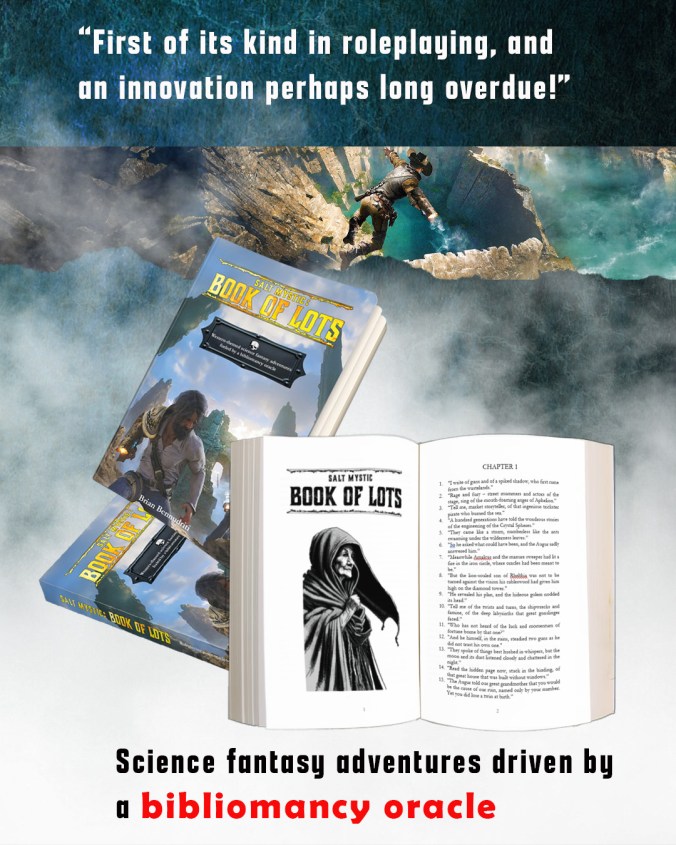

I’ve spent the last 3 years working on an approach to storytelling and tabletop roleplaying that I engineered to be as innovative as I could manage. I tried to rethink how narrative games like Dungeons & Dragons function and streamline everything down to core essentials.

“The awe and danger of exploration inside the covers of a book.” That was my compass. It’s here, called SALT MYSTIC: BOOK OF LOTS. I’m not trying to sell you that right now, though. I want to talk about using it as a recording studio like Wilson did.

This idea now of texture and layered elements building a rich tapestry to transform a familiar art form into something different and new prodded a new question for me:

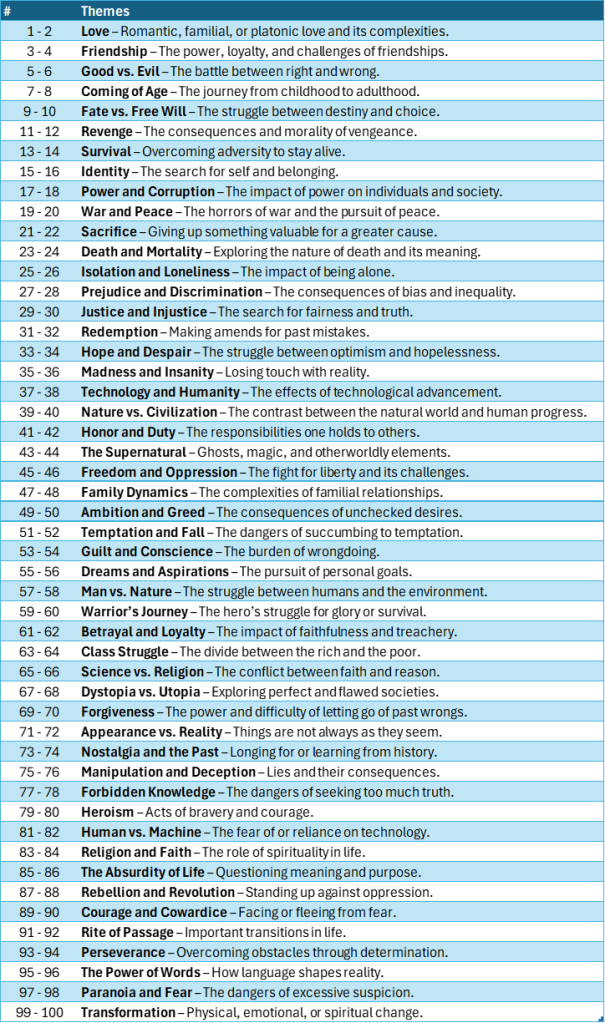

Can the elements of mythology and storytelling play the same role for the written word that musical notes, chords, and rhythms play? Instead of playing for the ear a rich tapestry like that, can archetypes and themes be arranged to play for the emotions?

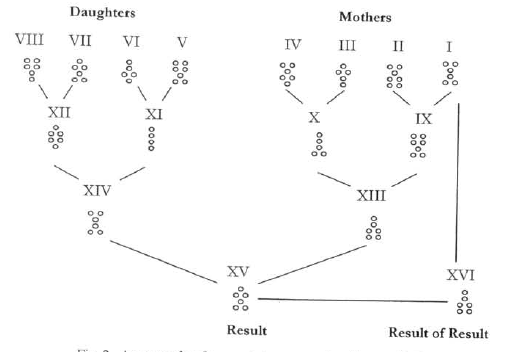

Here are the commonly accepted themes of mythology and folklore in a table, arranged into numbered entries appropriate for a roll of D100 dice:

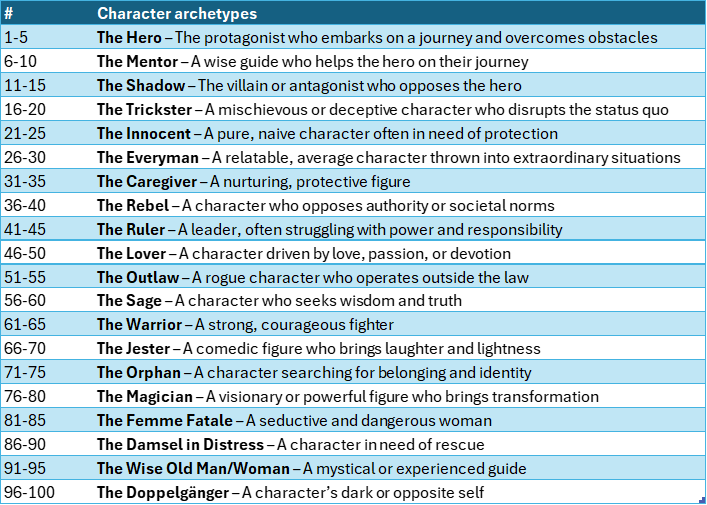

Here are the common character types of mythology, similarly arranged:

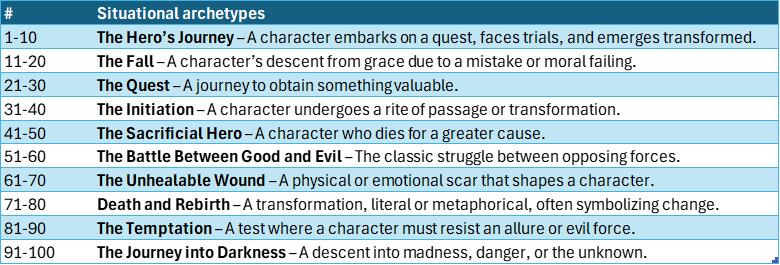

And finally, here are the common situational types of mythology:

SALT MYSTIC: BOOK OF LOTS is designed in a similar manner, with appendix tables for all manner of characters, encounters, and places arranged along the 100-scale like this, appropriate for idle shopping, dice rolls, or use of the bibliomancy mechanic core to the book’s function. The concept with the book is to forge a solo adventure and tell yourself an amazing, resonating story.

The analogy I’m drawing today is that themes and types of mythology have a power and resonance very much like the comforting, stable floor of bass in music. A deep, low melody on bass grounds a melody and makes it richer, makes it seem more important. That’s how myths work. I’m imagining incorporating elements from these tables into a solo tabletop adventure to make them play the same role…

…to summon them so they must work their magic.

I picture roleplaying game rulesets like the one in the BOOK OF LOTS as recording studios: an engine of creation that wasn’t available to previous generations that we can bend to dazzling new heights like Wilson did.

I see elements of oracle tables like those in BOOK OF LOTS or Ironsworn, Starforged, the Dungeon Dozen volumes 1 and 2, and other amazing sourcebooks as chords and notes.

And I see the solo player as a crazy artist, just messing with things to see what new comes out of it all. Telling new stories. Jamming new jams.

My head is swimming at the thought of this. I wonder if it’s too much coffee or if there’s something to be said, truly, about combinations of mythic elements arranged like music. Intriguing idea for me today, at least, to bring it to you today.

Till next time,