If you haven’t read the first part of this double-header, click here for part one. This is the final wrap-up of a two-part deep dive into the ancient Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 AD, to determine whether there was indeed a booby trap at the heart of the battle as some historical sources suggest.

Welcome back to our series called Inspirations From History!

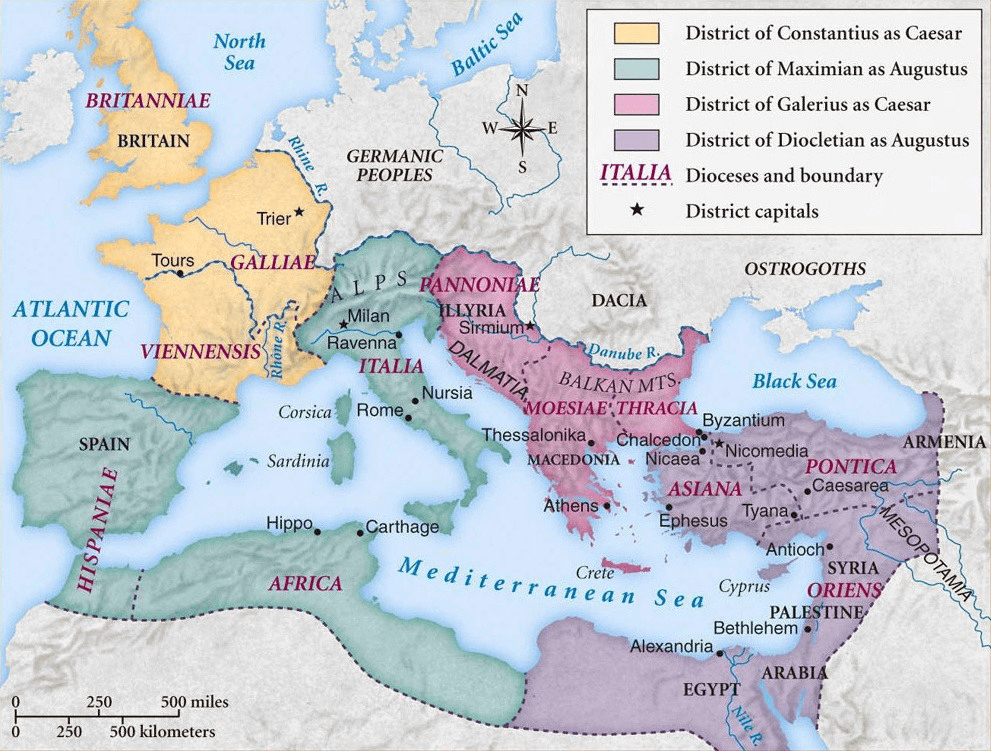

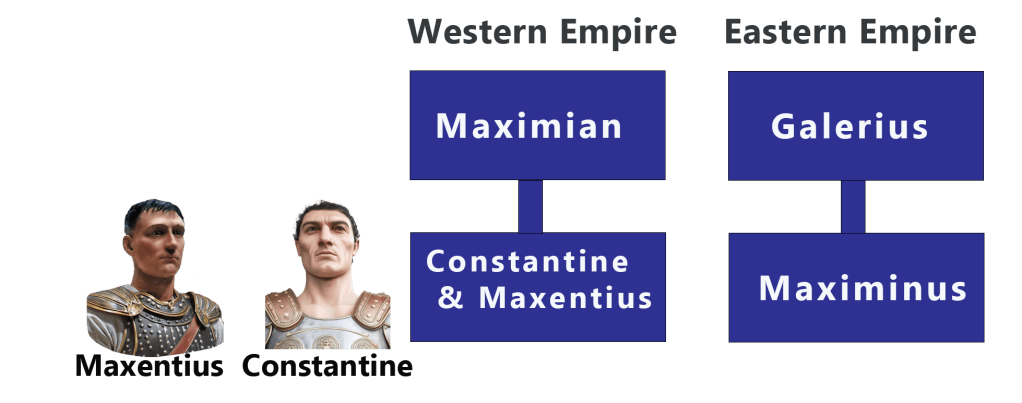

The purpose of part one was to set the stage for why the battle happened and put its importance in context. We also met the key players: Constantine and Maxentius, and roughed out a psychological profile to probe the mystery at hand. If Maxentius really was a wily coward, superstitious and cautious, who relied on subterfuge and undermining enemy forces for victory, then yeah – he might have laid a booby trap. Instead, if Constantine was just lucky and bold and a good propagandist willing to use superstition and religion to advance his agenda and to inspire his men, then maybe no – the booby trap could have just been his insulting re-framing of the battle afterwards.

Well, which was it?

Pretty sure I have a good answer to that. There are 8 key historical sources to examine, all with solid claims to people who were there, spoke with those who were there, or otherwise had access to credible sources. I got my hands on all of them.

(1) Latin Panegyric 12, from an anonymous author and dating to 313 AD, only a year after the battle and representing the words of a speech made directly to Constantine

The author describes Maxentius as growing gloomy and bitter at Constantine’s approach, rushing into a foolish formation, and panicking in his retreat. The narrowness of the bridge hindered the retreat, and the river “snatched up their leader himself in its whirlpool and devoured him when he attempted in vain to escape with his horse and distinctive armor by ascending the opposite bank“.

No mention of a booby trap.

(2) On the Deaths of the Persecutors by Lactantius, dating to 315 AD

Chapter 44 describes Maxentius as staying behind in Rome at the games while his men fought the battle until he was shamed to ride out to fight and received what he thought was a favorable oracle. “Led by this response to the hopes of victory, he went to the field. The bridge in his rear was broken down. At sight of that, the battle grew hotter.” Then on seeing he was losing, Maxentius “fled towards the broken bridge; but the multitude pressed on him. He was driven headlong into the Tiber.”

Still no mention of a booby trap, nor even Maxentius scheming by doing anything to the bridge.

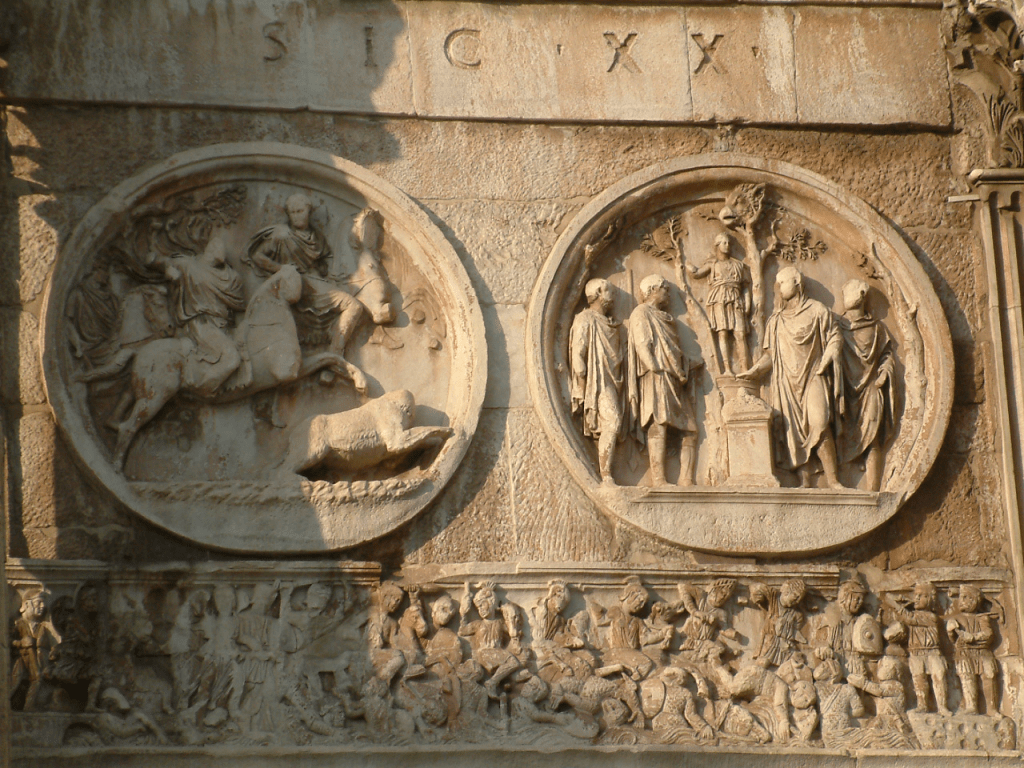

(3) Ecclesiastical History (between 312-324 AD) & Life of Constantine (337 AD), both by Eusebius and both would have been read by Constantine

In the older work, Eusebius says Maxentius and his men drowned “when he fled” as he “passed through the river which lay in his way, over which he had formed a bridge with boats, and thus prepared the means of his own destruction“. Further, “Thus, then, the bridge over the river being broken…immediately the boats with the men disppeared in the depths“. No mention of a booby trap here either, but a casual reference that might be made more clear as we go here. Stick with me on this longer quote below.

In his retelling of the story years later, the same author says of Maxentius, quoting more fully since it’s what inspired this entire quest):

“…when in his flight before the…forces of Constantine, he essayed to cross the river which lay in his way, over which making a strong bridge of boats, he had framed an engine of destruction, really against himself, but in the hope of ensnaring thereby him who was beloved by God.” Later, “…one might say he had made a pit and fallen into the ditch which he had made. His mischief will return upon his own head..under divine direction, the machine erected on the bridge, with the ambuscade concealed therein, giving way unexpectedly before the appointed time, the bridge began to sink and the boats with the men in them went…to the bottom.”

Constantine knew Eusebius well, and they would have definitely discussed this battle and its details, especially with Eusebius writing the guy’s biography. I can’t escape this account – the guy clearly says there was a booby trap.

Is that the answer, then?

Unclear so far. Let’s keep going. The other, equally old sources said nothing about it, in fact just the opposite.

(4) Latin Panegyric 4, by Nazarius, dating to 321 AD

Here, Maxentius is said to have arrayed his forces with disadvantage because he was “mad with fear“, in a “desperate state of mind and confused in counsel since he chose a location for the fight that would cut off escape and make dying a necessity.” The author’s first speech (now lost) would have covered more details, but he describes at least here the Tiber “filled with heaps of bodies” and an unbroken line of carnage “moving along with weakened effort among high-piled masses of cadavers, its waters barely forcing their way through“.

No mention of a booby trap here, just a panicked retreat. Constantine wasn’t actually present when this speech was made, but he would have surely received the text and, I imagine, people who saw the battle would have been there to hear it and challenge anything said that was incorrect.

(5) Origin of Constantine by an anonymous author, dating to 337 AD

This account, though brief, sums up the battle as follows: “…when Constantine had arrived at the city, Maxentius, leaving the city, chose a plain above the Tiber in which to fight. There, defeated, with all his men put to flight, he perished amidst the straits of the people who were surrounding him, thrown from his horse into the river.”

No mention even of the bridge itself, nor in fact a collapse or breaking of the bridge. It just says he was thrown from his horse in a presumed retreat. Definitely no booby trap mentioned here.

(6) The Caesars by Aurelius Victor, dating to 361 AD

A short recount from this source describes the battle as follows:

“Maxentius, growing more ruthless by the day, finally advanced with great difficulty from the city to Saxa Rubra, about nine miles away. His battle line was cut to pieces and as he was retreating in flight back to Rome he was trapped in the very ambush he had laid for his enemy at the Milvian Bridge while crossing the Tiber in the sixth year of his tyranny.”

Strangely, the recount of this senior bureaucrat in imperial service who possibly had access to good sources mentions an “ambush” but no booby trap. Eusebius had mentioned an ambush but said it was hidden by the booby trap.

(7) Epitome of the Caesars by an anonymous author, dating to the 360’s AD

This recount presents a very different twist to the story:

“Maxentius, while engaged against Constantine, hastening to enter from the side a bridge of boats constructed a little above the Milvian Bridge, was plunged into the depth when his horse slipped; his body, swallowed up by the weight of his armor, was barely recovered.“

No booby trap here either, though it’s thirty years later and this author is first to suggest Maxentius was possibly headed TO the battle, crossing the intact bridge, when his horse slipped. I can’t give any credence to this one due to its later date and its crucial variance from much older sources.

(8) New History by Zosimus, dating to the 5th & early 6th century but with access to much older sources

In part one of this series, I quoted the Zosimus passage describing the booby trap and its iron fastenings. The author continues describing the battle: “As long as the cavalry kept their ground, Maxentius retained some hopes, but when they gave way, he tied with the rest over the bridge into the city. The beams not being strong enough to bear so great a weight, they broke; and Maxentius, with the others, was carried with the stream down the river.“

So even though Zosimus had just described the booby trap as real, he doesn’t credit its triggering with killing Maxentius. Instead, it’s that the “beams” gave way.

Okay, so what’s the answer? Was there a booby trap?

No, it would seem there was not. Since most sources agree it was a rushed retreat and collapse of a temporary bridge, that’s likely what happened.

Where did the booby trap story originate, then?

This is something I learned as I researched this series: Constantine was a shrewd manipulator and propagandist. He had leveraged a supernatural vision before, and that wasn’t a Christian god. He leveraged a vision at Milvian. He painted himself as divine inevitability. This fellow knew Eusebius (a bishop) and the explosive new religion of Christianity as what they could do for him. It was very much to his benefit that he be the hero and liberator versus a wicked, scheming coward in Maxentius as this story was locked into history.

Constantine made it up. That’s my conviction after poring through these sources. He just made it up. And I’m here two millenia later half-believing it.

*

Anyway, this has been intriguing for me and a long-time interest I enjoyed researching for you. Apologies for going long on it, but the background seemed important. Let me know what you think and if you believe the question is settled or not.

Till next time,