Harlan would hate this. With a bullet. But it’s happening.

We’re making hay while the sun shines, trying out a premium ChatGPT subscription and bringing all sorts of people back to life or mashing them together into alternate realities for our entertainment. And honestly, some of these simulations of literary or artistic geniuses are surprisingly accurate to how they thought and spoke. So far, we’ve hosted a hilarious debate about conciseness in storytelling with Stephen King, Hemingway, Poe, H.P. Lovecraft, Professor Tolkien, George R.R. Martin, and Homer called Verbosity & Vine and had Professor Tolkien write a new 2,000 word King Arthur short story with an evil grail titled The Black Chalice of Broceliande. There is absolutely going to be a Seinfeld Season 10 post at some point, once I pipe Modern Seinfeld prompts into ChatGPT and let the horses run.

Anyway, welcome to a series we call:

Since the King versus Hemingway debate wound up so funny, we thought it would be a hoot to smash some more genius creators together and have them argue the merit of shock value in storytelling. To remind everyone: our policy at Grailrunner is to consider AI as powerful tools but to always call out their usage. This is for pure entertainment. Nobody’s selling you anything here.

This simulated argument was entirely written by AI with prompts from us, but really took on a life of its own. We decided who joined the conversation, and some of those choices really wound up fantastic. In fact, things really surprised us when we had Professor Tolkien join this conversation as well, as he kind of cleaned everyone’s clock on the matter at hand and got suddenly inspiring. That just happened – we can’t take credit for it! Ellison, at least for our part, stole the show though.

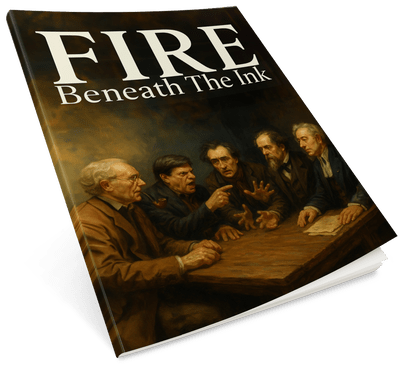

The conversation is called Fire Beneath the Ink:

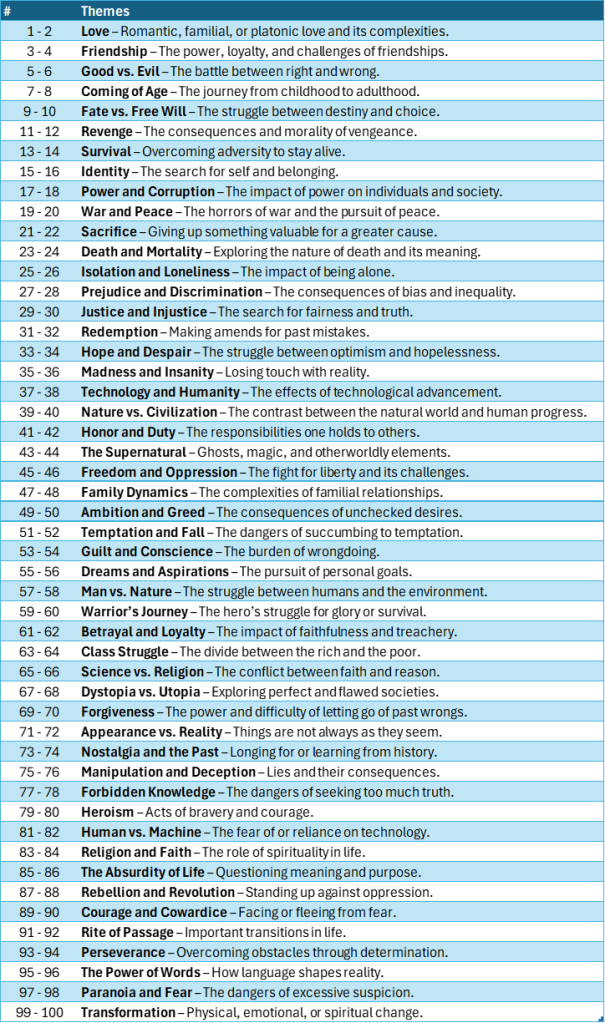

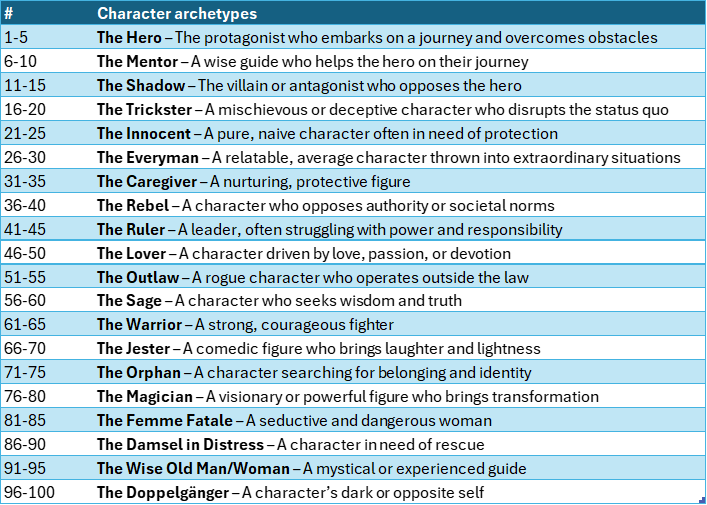

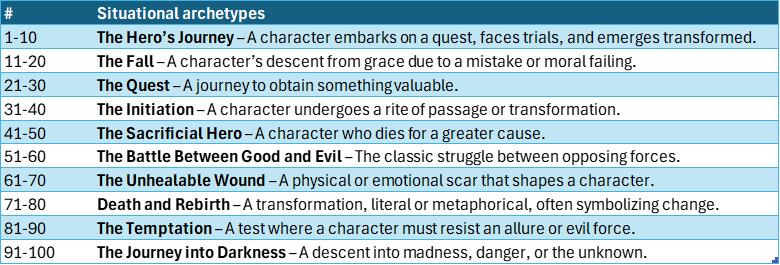

Key players (all deceased) from left to right are:

Professor J. R. R. Tolkien – author of The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings trilogy and master craftsman of worldbuilding.

Harlan Ellison – a fiercely imaginative and outspoken American writer known for his prolific work in speculative fiction, particularly short stories, television scripts, and essays that challenged social norms and literary conventions. Also one of the finest writers to ever punch a typewriter.

Antonin Artaud – a radical French dramatist, poet, and theorist best known for developing the Theatre of Cruelty, which sought to shock audiences into confronting the deeper truths of human existence. He once threw meat at his audience.

Charles Dickens – a celebrated English novelist and social critic whose vividly drawn characters and dramatic storytelling captured the struggles and injustices of Victorian society. Nobody has ever been better at generating pathos and character empathy than this guy.

Jonathan Swift – an Irish satirist, essayist, and clergyman best known for his sharp wit and scathing critiques of politics and society, particularly in works like Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal.

Random? Maybe a little. They all seemed to suit the topic at hand though, and Artaud and Harlan got along famously! See for yourself by smashing the cover button below!

So funny! We hope you enjoyed the debate. Somehow, it was nice to hear from Harlan again, and with him in good humor, poking at people and enjoying himself. If you’re familar with him at all, surely you see how much he would loathe this entire idea and likely drive to my house and tell me so.

And what about that Professor?! Did you get tingles at the end? We sure did.

Anyway, come back often and check on us. We’re unleashing the creative hordes here.

Till next time,