Oh, wow, if you could have been with me at a rainy beach in New Hampshire in 2015! I had a half-day to myself, off from work with a rainy New England afternoon free. I drove from Portsmouth where I was working down to Hampton Beach. It was cold, gray, and everything was closed for the winter. There was one couple on the beach trying to make a romantic walk of it, but it was the slow, drizzling, mean kind of cold rain that soaks into your bones.

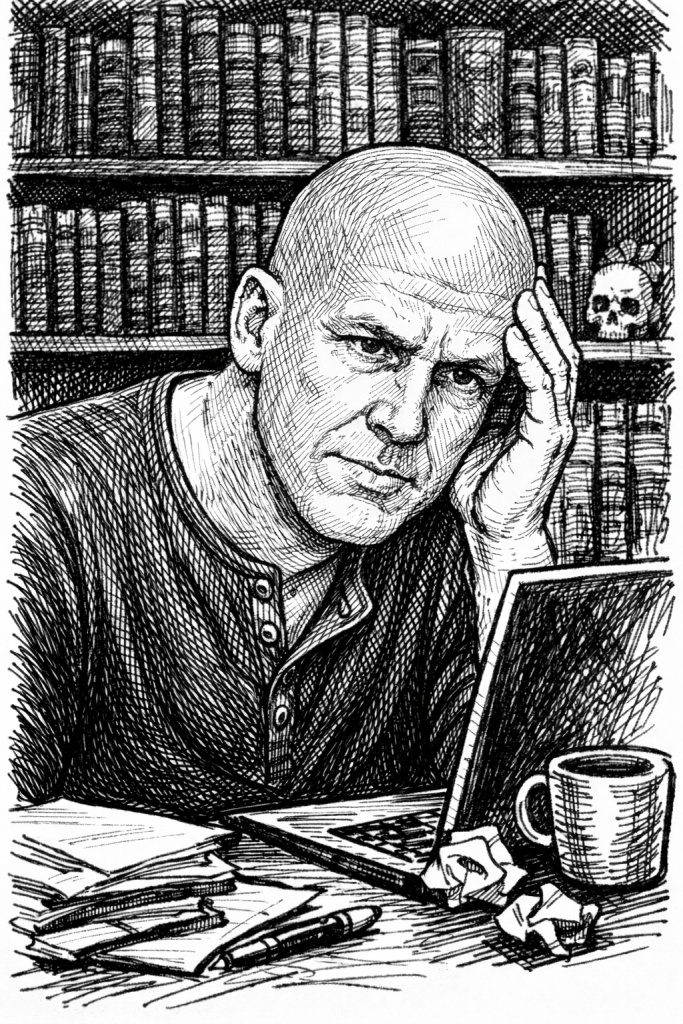

Most of the framework and plot of the novel I’d been writing for years had been rattling around in my head since my time in the Navy in the late 90’s. That’s a long time to cook the soup! I get that. And I’d been writing that book, my first one, for over 6.5 years. Almost 7. But I was close. All the threads I wanted to tie up were pretty much tied. I was planning to see if I could just park near the beach, prop open the laptop there in the car to the pat-pat of light rain, and see what I could do to carry things over the finish line.

There’s a statue of a lonesome woman staring at the sea there. I was down the beach some from her, facing the water same as she was. It was a great vibe, honestly. Not physically comfortable, but amazing for creative inspiration. And I did it! That last image…the last conversation…the final closeout I’d been looking for…it went onto the page all by itself. I couldn’t believe it! No one in the world to tell about it, and no one would probably even understand what a big deal that was for me, but it was truly done. Not rushed and not compromised.

Done, the way I wanted it.

What’s the big deal about that?

Writing a novel is challenging to every aspect of your life. Time spent writing is time away from your family. It’s time not working on your day job. And it’s hard – ridiculously hard! Stories grow more complex than you wanted, and characters change from what you made them to be. Dialogue that sounded awesome in your head repeats back as strained, alien, and as plot dumps when that wasn’t what you intended at all.

I was trying to earn my way, be a husband and a father, but still turn visions in my head into something real that could say something meaningful and outlast me: a world people could step inside. But I felt selfish every time I wasn’t playing a game with my wife or watching a movie with my daughter or taking my son fishing. Writing a novel is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, but also one of the most life-altering. It changed me for the better.

Okay, so what are we talking about here?

It takes too long. That’s what I’m saying. Need to fix that. I’m over 4 years in to the novel I’m writing now. Not cool if I’m still banging away on it for three more years.

Talk to me, Grailrunner – how do we speed up the creative process?

If you’re a novelist, like the kind of folks who might read Grailrunner and nod, you feel the tug of two opposing forces:

- You want your story clean, logical, tight, like a well-made blade

- You write in spirals, rewrites, loops, hollows — messy, intuitive, iterative

Tell me I’m not alone in that. Anyway, it feels like a flaw to rewrite because it feels like starting over. I’m thinking in layers, but trying to polish before I’ve built the foundation.

But it struck me recently that concept artists have figured this out!

Many visual artists, particularly concept artists, work in ways that seem counter-intuitive. They don’t sit down with a crystalline vision of what they expect the final image to look like. Instead they check the brief and then:

- Lay down marks, then react

- Let accidental shapes guide the next decision

- Build texture before form

- Play off of unexpected accidents

- Iterate forward, not backward

I wondered for myself then – this idea of a visual artist pressing ahead with abandon, careless of the final picture, knowing there will be revisions later but enjoying the process for itself and riffing off what they lay down – could that help me?

And?

Here are five principles I’m locking in for myself – maybe they’ll be helpful for you:

1. Generate the back cover text now

I built the entire cover for the book, including the artwork, but more importantly the back cover text. I printed it off in glorious color and even folded it into the size and shape of the final product so I could hold it in my hand. I needed that kind of focus on the story I’m telling (and why) to help me trim shiney bits and bobs that kept raining down from the sky. It’s a laser beam now. Anything not feeding that back cover promise is out!

2. Tell someone the one-line summary of what the book is about

My brother surprised me with the question when I was hip-deep in an action sequence and I hated my ill-prepared, off-the-cuff answer so much I called him two days later with a sharper and better one. Now, it’s like a mantra in my head helping me stick to that promise too. Like the back cover exercise, but even tighter!

3. Get to know the characters better before forcing them into a pre-defined plot

I spent some quality time just extrapolating for myself on what the main folks care about, what they’ve been up to when they’re not “on screen”, and some great backstory that might never make it to the page. AI tools like ChatGPT can accept your work-in-progress manuscript and engage with you in full conversations in those character voices. Crazy way to create a work of art, but an interesting way to immerse yourself in your own story!

4. Draft without editing – for real this time

I press ahead now on the chapter at hand. Just blast it out as intended, almost in a rush, to lay out the skeleton of what’s supposed to happen and let these people do what I know they would do. Tomorrow, I’ll go back over it again and catch the nonsense and the plot holes, the contradictions. Like the concept artist checking the brief, but then just laying down random marks according to what seems right, I’m applying that to the written page. The difference is the freedom now to avoid stopping constantly, in real-time, to worry over whether something makes sense right now and stop to fix it immediately.

5. Accept it when cool things need to die because they no longer fit

Oh, it’s hard! I liked Ilianore a lot, but you’ll never meet her. The climactic spearing from the sky – pretty sure that’s gone too. A midnight flight on a train – also gone. I’m trying, man. I’m trying to turn things loose now when they seemed so amazing but just don’t match up with where things are going or what these people would do. I’m considering short funerals for some, but for sure I’m pasting some of that old text into a document to save in a folder somewhere in case it ever needs to come back to life. Director’s cuts, sort of.

Anyway, that’s what I wanted to bring you today. These principles are speeding things along for me, at least. And I’m noticing a lot less hair growing on the plot these days. Less massive revisions are even necessary. Let’s hope that’s the process working its magic and not also my imagination.

Till next time,

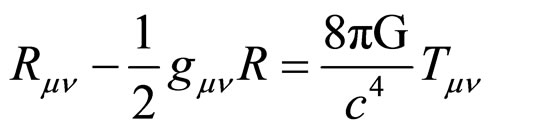

Here they are: Einstein’s Field Equations defining gravity. Why things fall down. All the jibber jabber on the left-hand side is just saying that spacetime curves. It doesn’t say why, just that it does. Einstein came up with all that on the left just to make the math work out, not because he was a prophet or anything. But he started with the doohickey on the right…the ‘T’. He knew he’d use that, and the idea that energy is conserved; and then he just started diddling around to see what he could do with it. Let’s say that was his original inspiration, the way a writer might suddenly string two things together to make a story idea. How pregnant with potential and thrilling, right! So what’s ‘T’, then?

Here they are: Einstein’s Field Equations defining gravity. Why things fall down. All the jibber jabber on the left-hand side is just saying that spacetime curves. It doesn’t say why, just that it does. Einstein came up with all that on the left just to make the math work out, not because he was a prophet or anything. But he started with the doohickey on the right…the ‘T’. He knew he’d use that, and the idea that energy is conserved; and then he just started diddling around to see what he could do with it. Let’s say that was his original inspiration, the way a writer might suddenly string two things together to make a story idea. How pregnant with potential and thrilling, right! So what’s ‘T’, then?