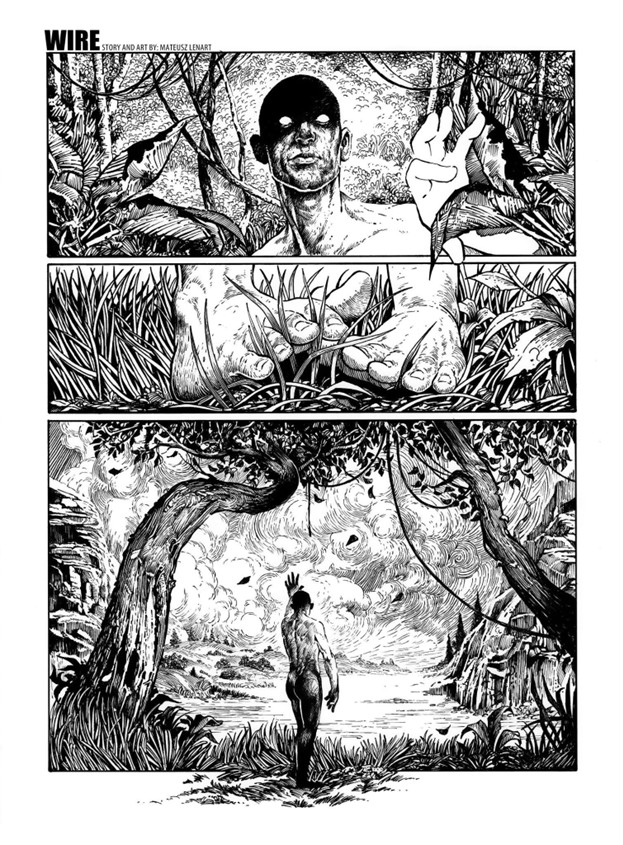

At Grailrunner we thrive on conversations that sit at the crossroads of imagination and craftmanship. Mateusz Lenart doesn’t just know the place – he’s set up shop there and is drawing crowds! From his role as Creative Director at Bloober Team (Layers of Fear, Observer, Blair Witch, The Medium, and the Silent Hill 2 remake) to his own powerhouse artwork – especially in traditional pen & ink, Lenart brings an artist’s eye, a comic reader’s energy, and a storyteller’s genius into the ever-shifting worlds of modern games and illustration.

Welcome to Grailrunner, Mateusz! And welcome to our ongoing series titled:

1. When we spoke to game designer, Jake Norwood (The Riddle of Steel), he mentioned a fascinating Polish RPG called Dzikie Pola. Polish fantasy author Krzysztof Piskorski (Tainted Grail) is a long-time target of ours for an interview to cover his incredible fantasy worlds. And if we’re talking Tainted Grail, we’re talking illustrator, Piotr Foksowicz – also Polish. And here you are, scaring the crap out of us with groundbreaking psychological horror in video games! Is there something awesome in the water over there?

Well, I can’t reveal too much just yet, but what I can say is that at Bloober Team we’re very much committed to pushing the boundaries of psychological horror. We’ve recently announced another remake in the Silent Hill franchise – this time going back to the very beginning with the first game – and not long ago we released Cronos: The New Dawn, another horror experience from our studio. Our portfolio has always been about exploring the darker corners of the human mind, and we intend to keep building on that tradition with future titles.

2. You mentioned in a previous interview that American comics from the 90’s were a big inspiration for you to get into art. Can you elaborate on which comics or graphic novels stood out for you, and especially tell us why that was?

A lot of what inspired me came from whatever I could find in the newsstands in Poland — Kioski Ruchu and the like. As most of the kids I devoured the Spider-man and Batman series in particular, even though it wasn’t always easy — my parents weren’t thrilled about me reading them! Those American comics were flashy and visceral, with dynamic art, dramatic panels, and strong emotions. Todd McFarlane’s Spider-man work was unforgettable — the exaggerated lines, the energy of the webs, the theatrical villains.

Beyond the American stuff, European comics played a big role in shaping me, too. I was deeply influenced by Thorgal by Grzegorz Rosiński, and also by the Yans series from the same author — their storytelling, the textures, the atmosphere — all of that showed me other ways comics could work. And then there were lighter, fun reads like Asterix, which taught me humour, caricature, and the power of visual pacing.

3. If I’d peeked over your shoulder as a kid, what would I have seen on the page—spaceships, monsters, superheroes, or something stranger? Why?

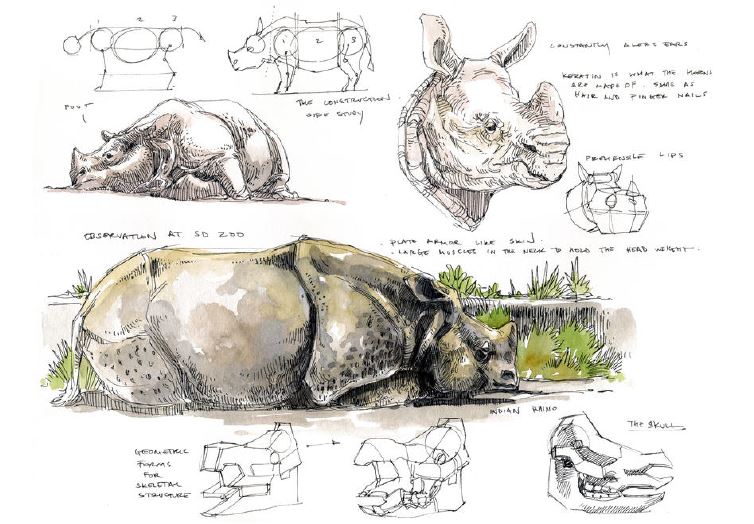

Honestly, a bit of everything. I was a pretty meticulous and disciplined kid — I somehow knew early on that learning anatomy would help me in the future, so you’d probably see a lot of sketches of hands, muscles, poses, often copied from anatomy books. At the same time, for fun I was constantly drawing fantasy characters — monsters, elves, knights — usually with little RPG-style stats written next to them for strength, dexterity, and so on.

You’d also find plenty of comic book pages. I loved inventing huge worlds and epic storylines, though most of them lasted maybe two or three pages before I’d abandon the project and jump to the next idea.

And, of course, there was always a darker tone in what I created. I don’t really know why — maybe because the darker stuff always felt more alive to me: more dynamic, more energetic, more full of contrast. That fascination with atmosphere and intensity stuck with me and never really left

4. Polish art, architecture, and history thread through your work. Can you share a specific real-world reference or point of inspiration, maybe even folklore, from your country that shows up in your illustration or concept art?

To be honest, there weren’t that many Polish references in my earlier work. Occasionally they appeared — for example, in The Medium I illustrated the towers of St. Mary’s Basilica in Kraków — but Polish architecture or folklore was never my main source of inspiration. At that time I was probably more fascinated by the topography of Middle-earth than by Poland itself.

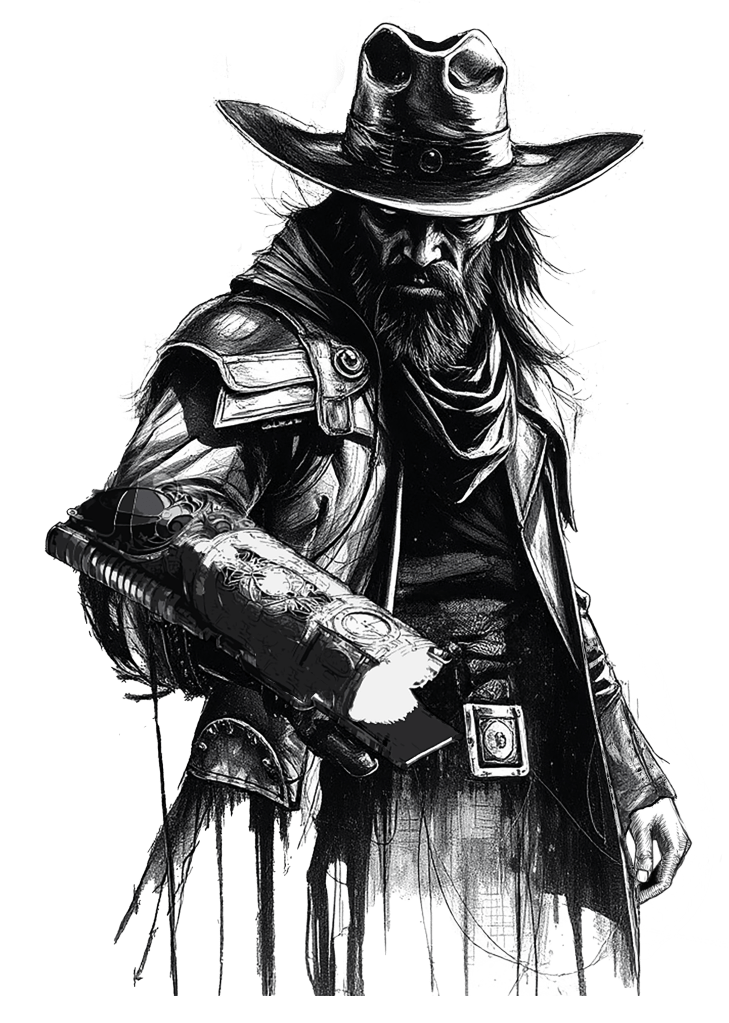

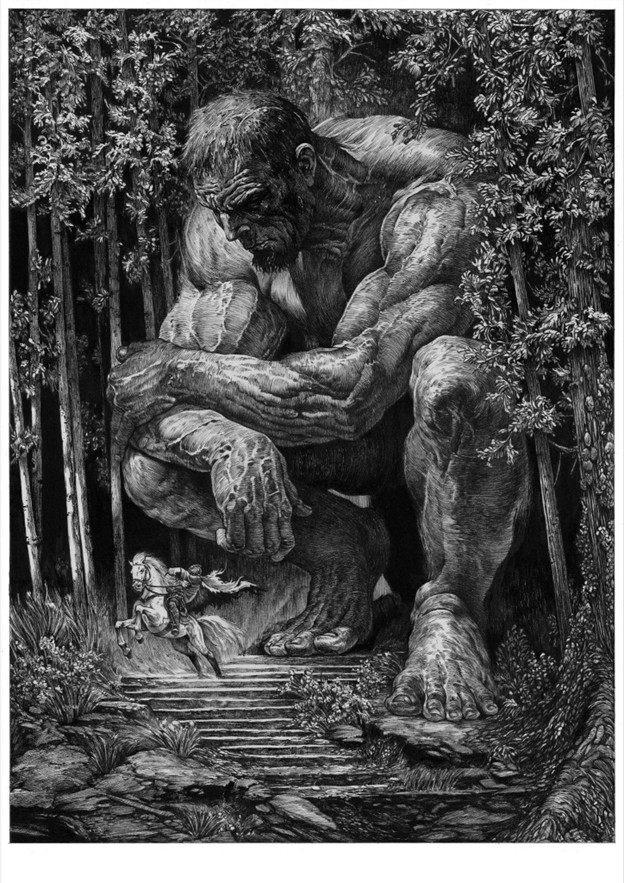

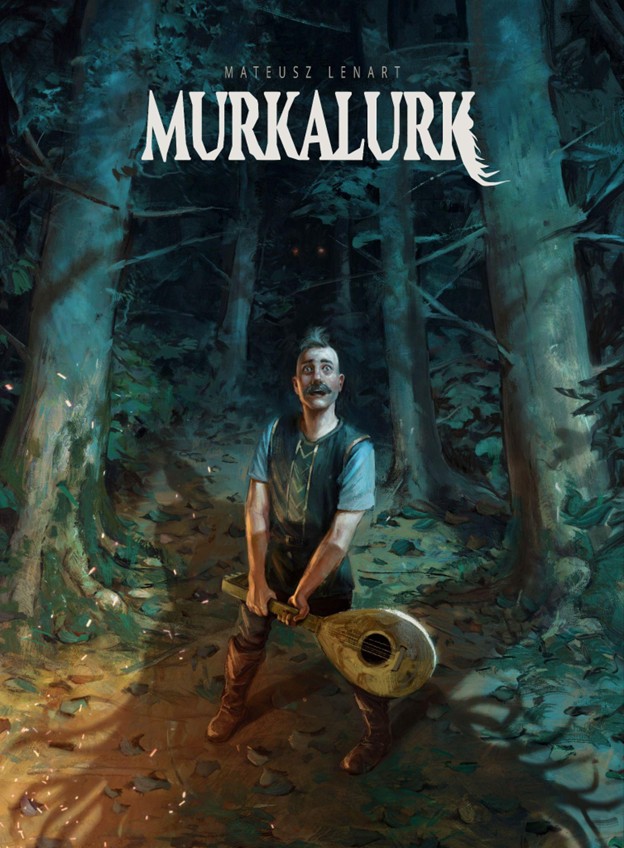

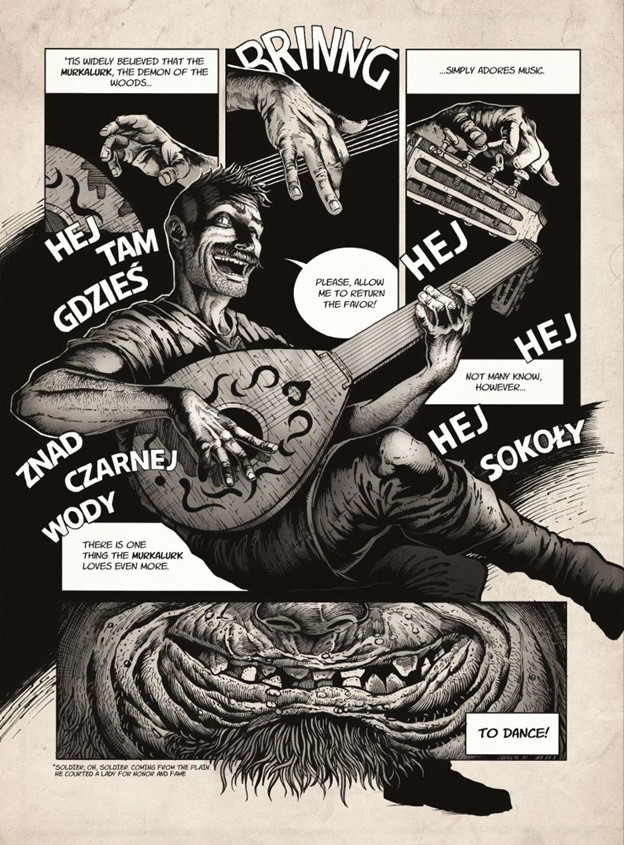

That has changed a bit in recent years. I’ve become much more interested in Slavic mythology, and it’s starting to influence the way I build my own stories. One small experiment was a short comic I created called MURKALURK, which tells the story of an unlucky bard who crosses paths with Slavic demons. Right now, I’m also working on a bigger project — a fantasy world that draws heavily from Slavic myth and culture. So you’ll definitely see more of that in my future work.

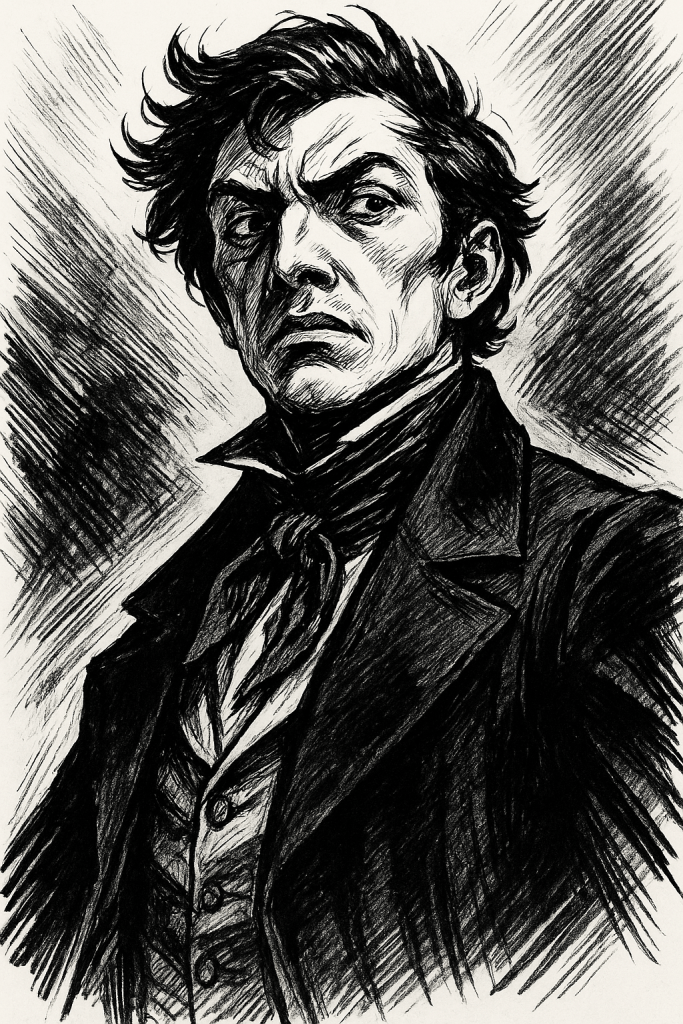

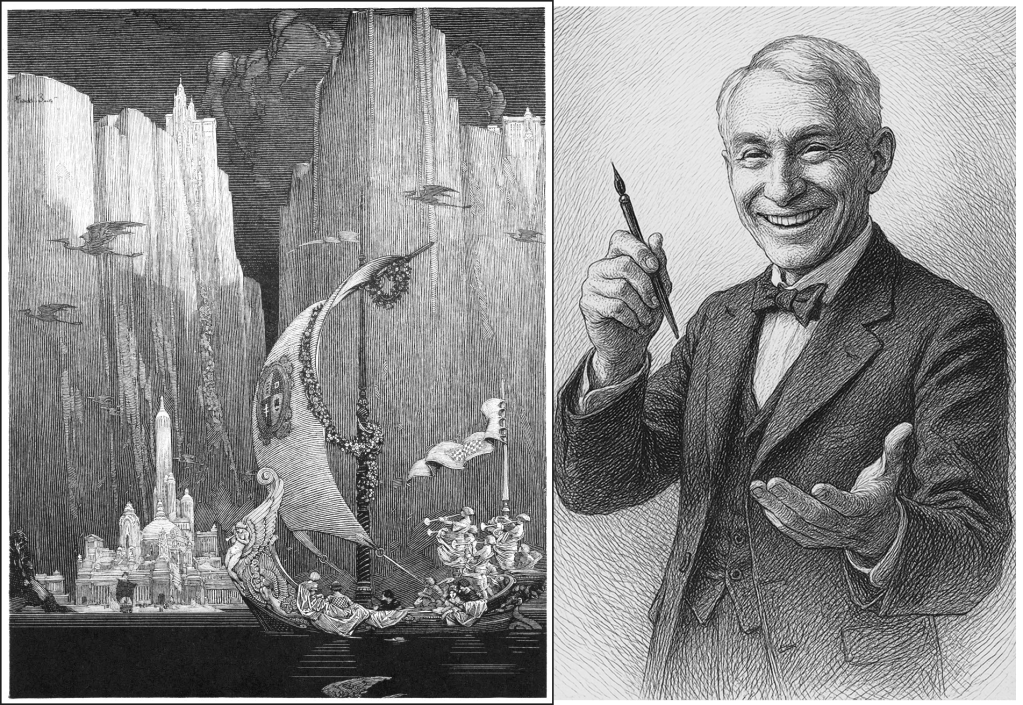

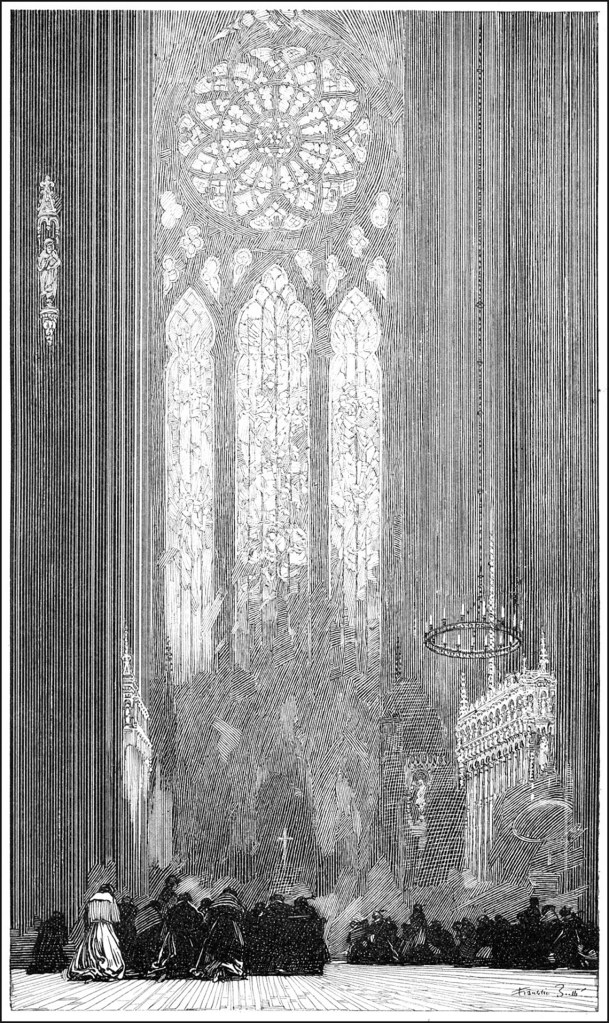

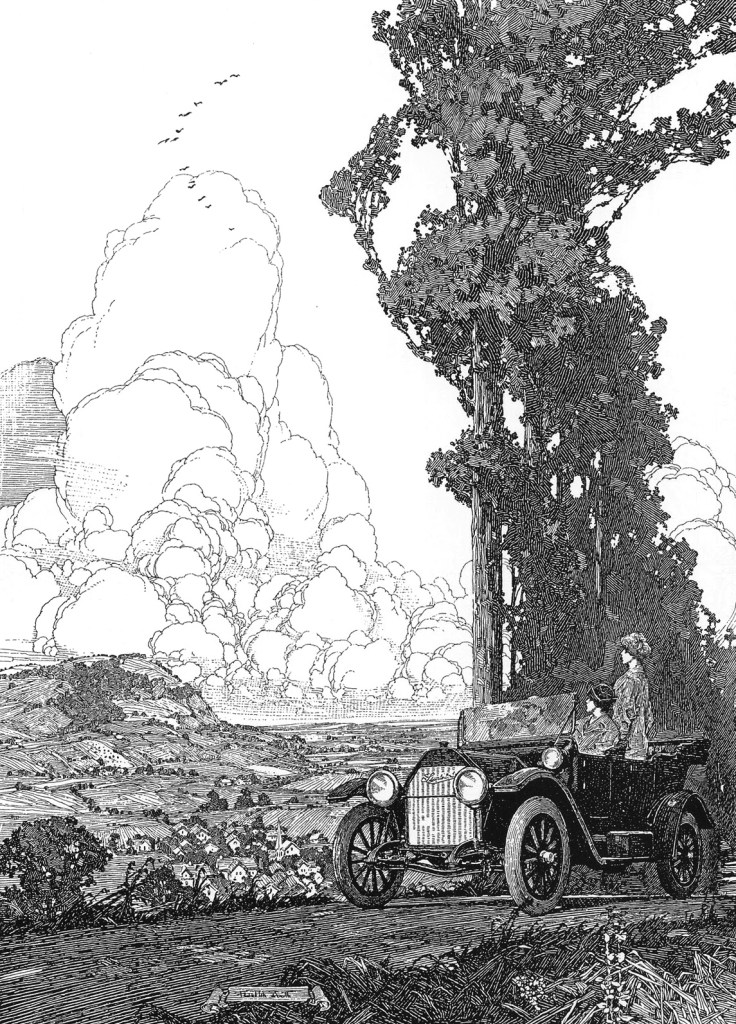

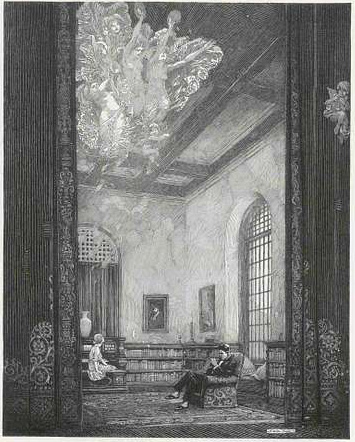

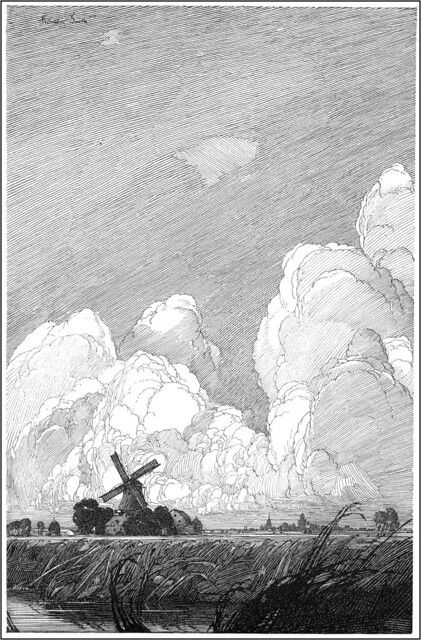

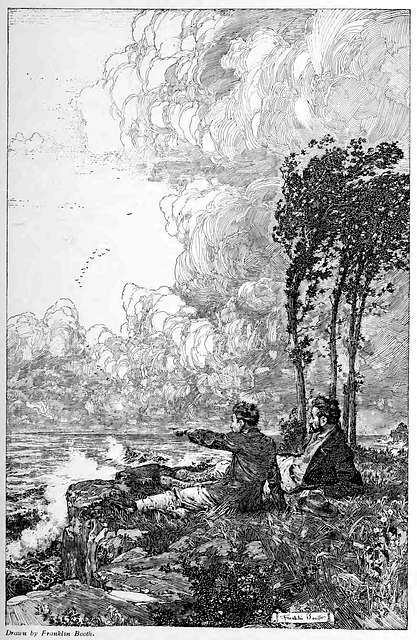

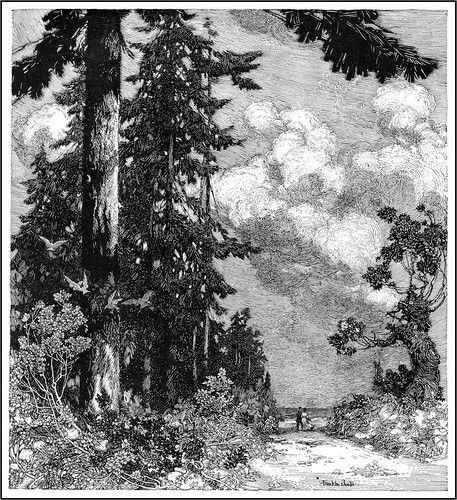

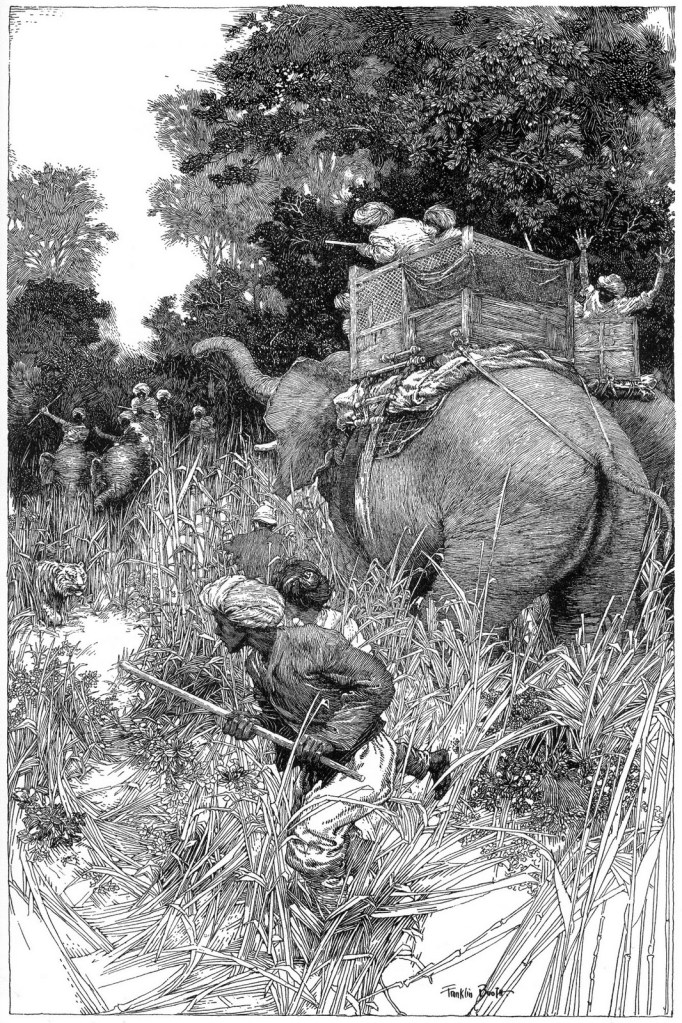

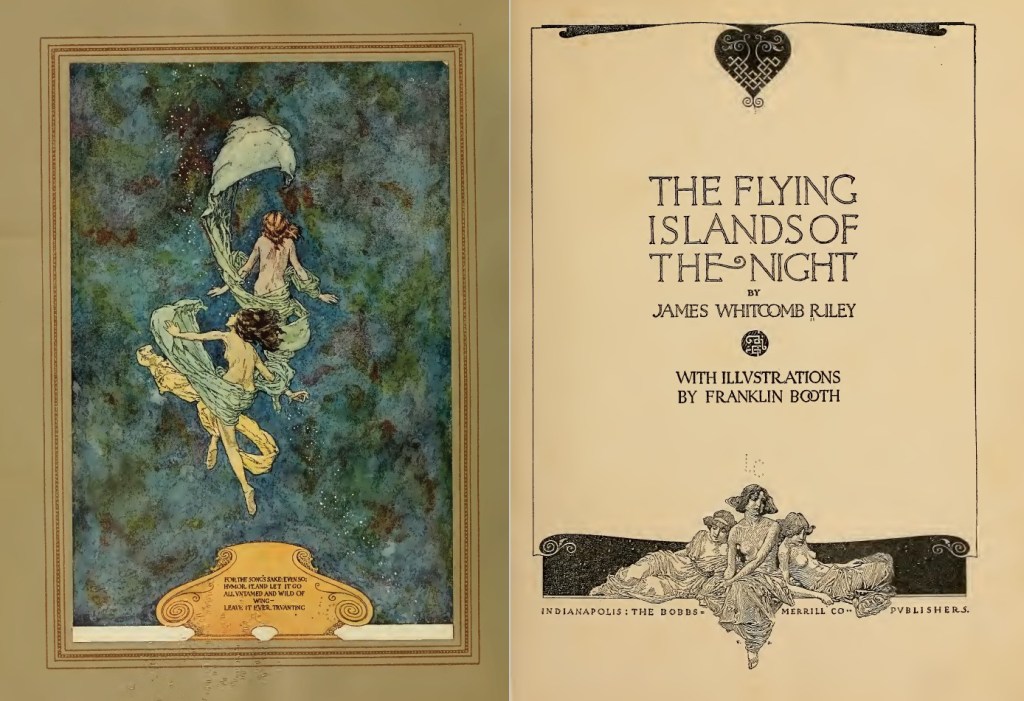

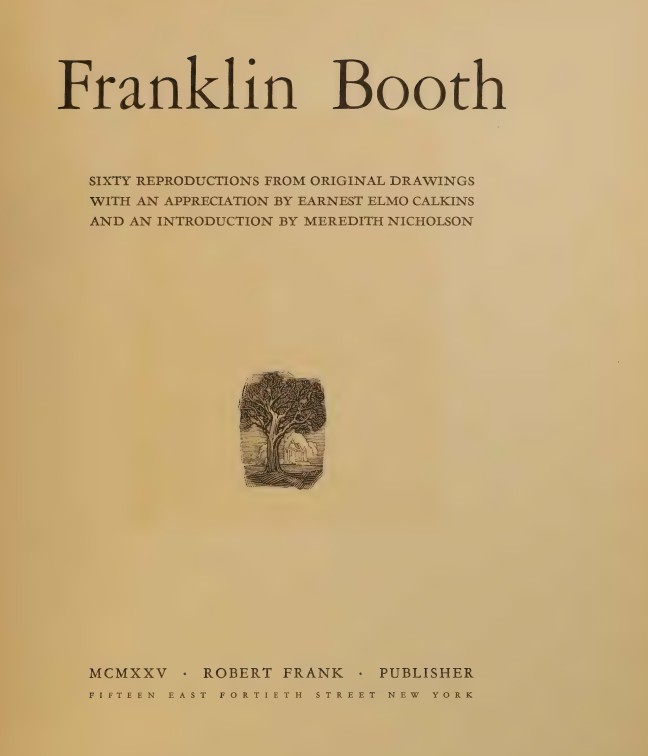

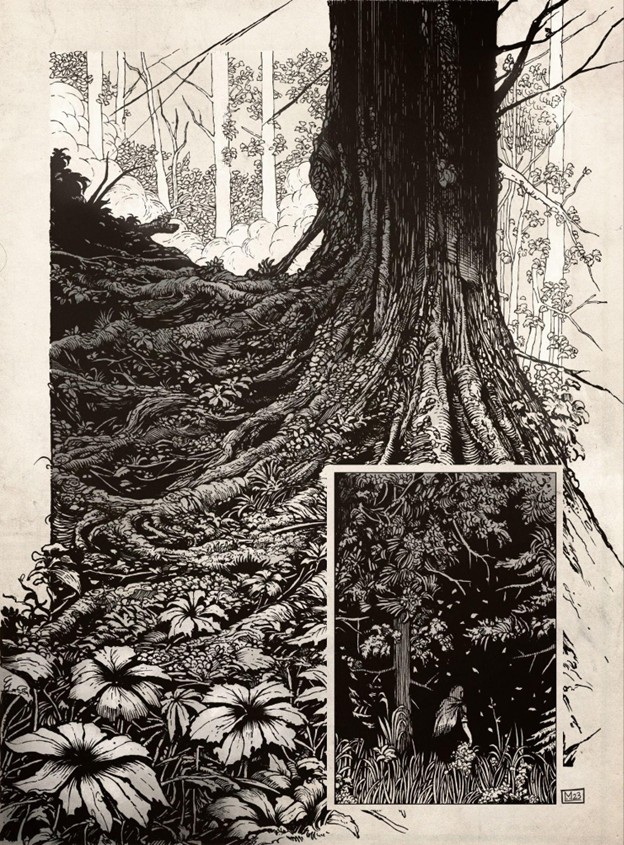

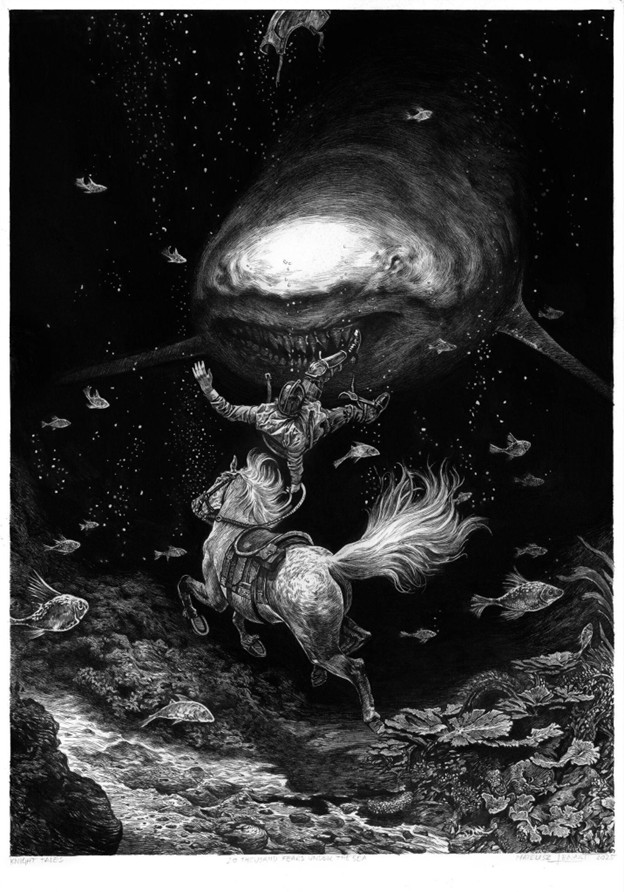

5. Awesome. Simply awesome. Why traditional pen & ink? I’ve got to say, when you mentioned 19th century master, Franklin Booth in a previous interview, I got incredibly excited. The guy was on a different level of genius! You also cited Gustave Dore, Bernie Wrightson, and Joseph Clement Coll. What is it about that kind of art that attracts you?

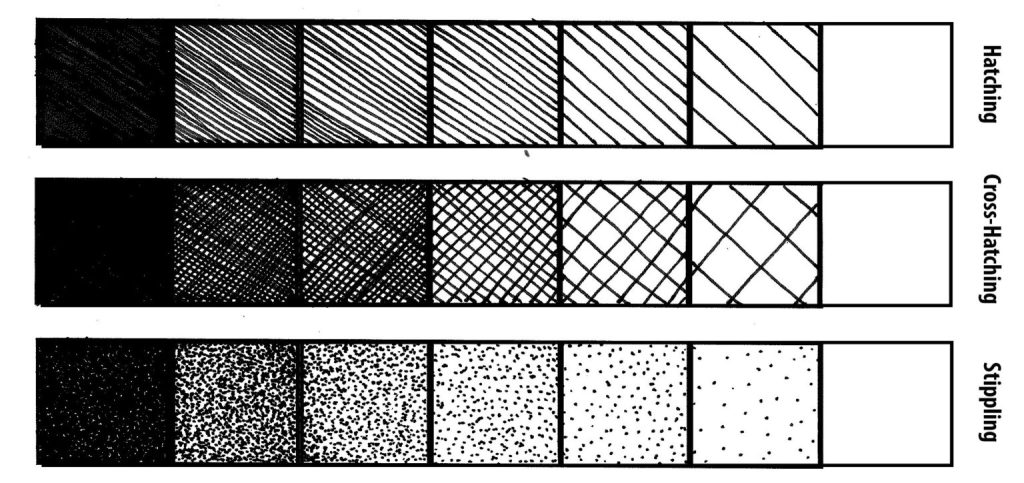

There’s something incredibly powerful about telling a story only with line and value — no color, just light and shadow, rhythm and texture. For me, pen and ink has always felt like the purest way of drawing, where every stroke is deliberate, every line carries weight.

I’ve also always been better in black and white than in color. When I discovered artists like Franklin Booth or Joseph Clement Coll, it opened my eyes to how far you could go with nothing but ink — whole worlds built out of contrast, atmosphere, and detail. There’s a timelessness to that style that I find endlessly inspiring.

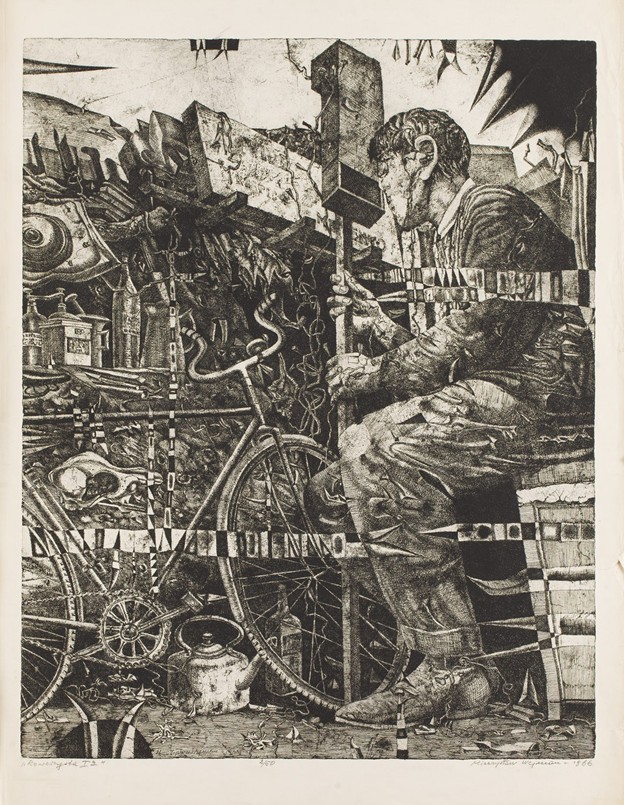

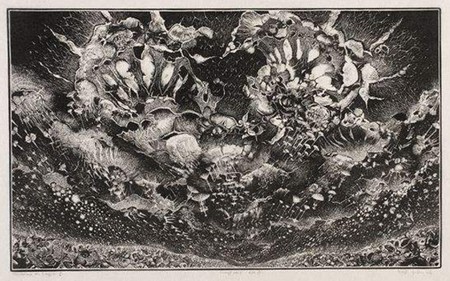

At the same time, I was very drawn to traditional printmaking techniques such as aquatint and linocut. I remember being deeply impressed by the works of Józef Gielniak, especially his Variations for Grażynka, and by Mieczysław Wejman’s aquatints like The Cyclist. When I was a student, I actually imagined myself working with those techniques professionally. But life took a different turn, and I didn’t continue down that path. In a way, pen and ink became a perfect substitute — it gives me a similar sense of precision, rhythm, and texture, without the technical limitations of printmaking.

6. Re-cycle

Your animated short Re-cycle is a striking, personal work. What first inspired the idea, and what challenges did you face in bringing it to life? Looking back, how did it shape or grow you as an artist?

I’ve always been someone who can’t focus on just one thing at a time — which is both a blessing and a curse. I started out as a concept artist, but quickly became fascinated with 3D, animation, design, lighting, and filmmaking. It was also a period when Polish short animation was experiencing a renaissance, with creators like Tomasz Bagiński, Damian Nenow, and Grzegorz Jonkajtys making work I deeply admired and wanted to create myself.

I honestly don’t remember exactly where the idea for Re-cycle came from, but, like many of my projects, it carries rather somber tones rather than cheerful ones. It was an interesting project — had I finished it in two years, it might have completely changed the path of my career.

In reality, it took seven years to complete because I kept being pulled into other work. By the time I finished, I was very tired of it, and the technology I had used was already outdated. Looking back, it taught me a lot about perseverance, about balancing multiple interests, and about how long-term projects shape your patience and vision. I do want to return to animation, but to do it properly I’ll need a lot of dedicated time to fully immerse myself in the craft again.

7. Our readers will kill me if I don’t ask about The Medium and Silent Hill, for which you served crucial creative and director roles. What can you tell us about those experiences bringing true psychological horror into the world that made you better as a creator? Did anything from your ink drawing practice or comic-book eye make its way into these massive productions?

Working on The Medium and Silent Hill was incredibly satisfying, but also very different experiences. On The Medium I served more as an art director — helping to shape the Other World — and getting to build an environment inspired by Zdzisław Beksiński’s work was a deeply powerful experience. Trying to translate that kind of surreal, decayed atmosphere into something the player could actually move through taught me a great deal about tone, detail and restraint.

Silent Hill was a step up in both scale and responsibility: the stakes were higher and my role covered design, art and direction. Revisiting one of the most iconic names in horror history is never easy, but it was hugely rewarding. The biggest challenge there was balancing respect for the original material with the need to bring something new and playable to a modern audience — and doing that across a large, multidisciplinary team forces you to be both precise and flexible.

My ink-drawing practice and comic-book eye absolutely found their way into those productions. The lessons of black-and-white work — composition, the economy of line, the power of contrast and negative space — translated directly into how we thought about lighting, silhouettes and level composition. Likewise, the way comics use panel rhythm to control pacing informed how we staged encounters and revealed information to the player: timing, framing and the gaps you leave for the audience’s imagination are universal storytelling tools.

Finally, these projects made me a better creator because they pushed me to scale my instincts. Working on a single illustration is a private act; working on a game means sharing to others your visual language, iterating under constraints, and learning when to cut or simplify for the sake of atmosphere. Film, comics and games aren’t as far apart as they seem — they share the same fundamentals: composition, emotion and the building of tension — and those cross-medium influences keep feeding my work.

8. When you need to design something truly frightening, what rituals or shifts of perspective get you into that mental space—and do you step back out of it deliberately, or carry it until the work is done?

It really depends on the situation. Very often, the things that frighten me most are those that aren’t meant to be frightening at all — finding that uncanny element in an otherwise ordinary scene creates the strongest tension. When you work on horror for a long time, though, you almost become numb to it. Stepping away and then returning to the work helps a little, but you can never truly see it with fresh eyes again. That’s why outside feedback is so essential — we rely on it constantly.

As for rituals, I don’t think I have any special ones. Creating horror, for me, is like any other kind of work: it’s a mix of knowledge, experience, and ideas. To paraphrase Stephen King, most of the time I feel more like a craftsman than a visionary — applying what I know to get the job done. Of course, there are moments of revelation, flashes of inspiration, and when they come you have to grab them and use them. But most of the process is simply the hard, patient work of solving problems over the course of a long production.

9. When you start concept art for a new character or environment, what’s your first step—gesture, thumbnail, written note—and how do you know when that early sketch has ‘spark’ worth pursuing?

It’s a difficult question, because the process can vary a lot. Technically, I almost always start with silhouette, shape, and energy on the page. There are countless tutorials that talk about the power of form, proportion, and so on, and those things are important — but for me the idea itself is what really pushes you forward.

Sometimes a written description of a monster or a character is already enough to spark something interesting. Other times, you have to brute-force your way toward a good idea through dozens of iterations, hoping that at some point something will ‘click.’ References also play a huge role in this stage. Collecting and studying them often triggers unexpected solutions — they can turn a generic design into something unique.

Recognizing the moment when a sketch has enough spark to move forward is always tricky. In my role as creative director, I often have to make that call, and it’s easier when you’re not personally involved in the painting itself. In my personal work, I usually just follow what excites me most, even if I can’t fully explain why. Sometimes it’s purely instinct — you sense there’s something worth pursuing, and you trust yourself to chase it. I’m also aware that, in doing so, I may be overlooking ideas that others would consider stronger.

10. Anything else you’d like to tell us about, including how we can see more of your work?

I try to stay as active as I can creatively. As I mentioned earlier, my biggest problem is that I always want to do everything at once. I’m still working at Bloober Team on our next title — it’s a long process, and one I’ll only be able to share more about in the future.

On the personal side, I recently released a comic/illustrated album called Murkalurk, which was received warmly and motivated me to start working on a larger comic project, loosely inspired by Slavic mythology. Right now, I’m deep in the stage of building characters and writing the story, which is why I haven’t shared much new work online lately.

There’s also my ongoing series The Knight’s Tale, created in traditional pen and ink. I hope to find the time to add new chapters to the story of that lost knight. As always, there’s never enough time and far too many ideas.

Hopefully, you’ll be able to see some of these new projects soon on my social channels — mainly on Instagram.

Thank you for the talk.

Thanks for your time and the wonderful art you’ve sent along for us to appreciate! Hopefully we can connect again in the future to see what you’ll have been up to!

*

Mateusz Lenart is an impressive bridge strung between ink and pixel, between the quiet scratch of a pen and the thunder of a horror score. His work reminds us that the best creators aren’t defined by tools but by vision: a sketchbook line that can grow into a world, a half-remembered comic that becomes a camera angle, a personal short film that seeds a new way of seeing. At Grailrunner, we often say “Dreams are engines. Be fuel.” In Mateusz’s hands, those engines are ink-black, smoke-stained, and unstoppable. And we can’t wait to see where they carry him next.

Till next time,